Trade Deadline Day seems a perfect creation for 24-hour sports television and all-sports radio. In Canada, TSN first aired a one-hour trade deadline broadcast 20 years ago in 1998. It’s been giving a major commitment of time to the Trade Deadline since 2001. In our current age of social media, tracking trade rumors has become almost a full-time job for some reporters. Teams’ fears of losing a free agent for nothing help fuel speculation that big names may be on the move, although salary cap considerations can make star-powered trades difficult.

But, of course, the NHL Trade Deadline is much older than the Internet and salary caps. How much older? In a year in which the NHL has marked its 100th anniversary, deadline day dates back those full 100 years to February of 1918. In fact, the concept of a trade deadline in professional hockey is older than the NHL, dating back another 10 years to 1908.

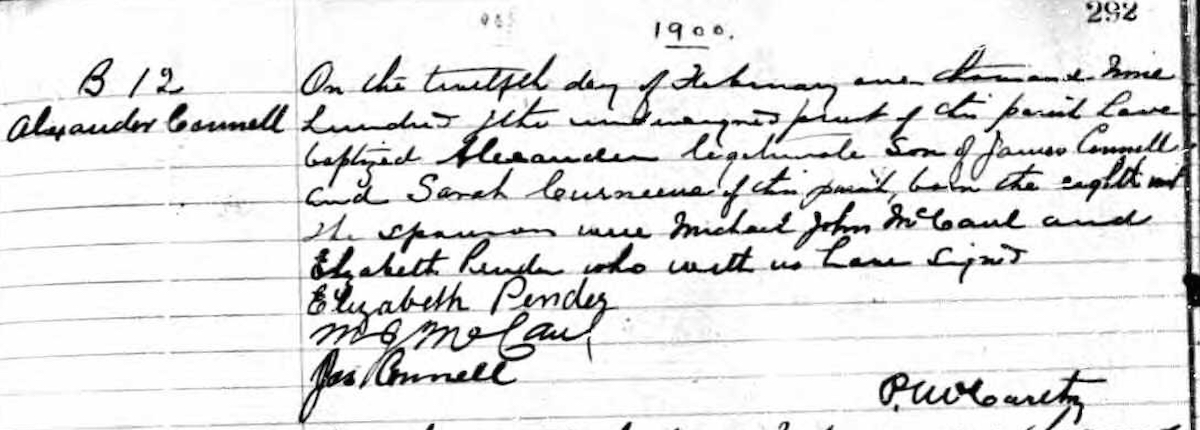

The first season in Canada in which hockey teams could openly pay salaries to their players was 1906-07. There had certainly been some form of “under-the-table” payment prior to that season, and teams had been known to bring in “ringers” for Stanley Cup games for several years already. But with professionalism, teams openly buying the best talent before big games was giving hockey a bad name. Something had to be done.

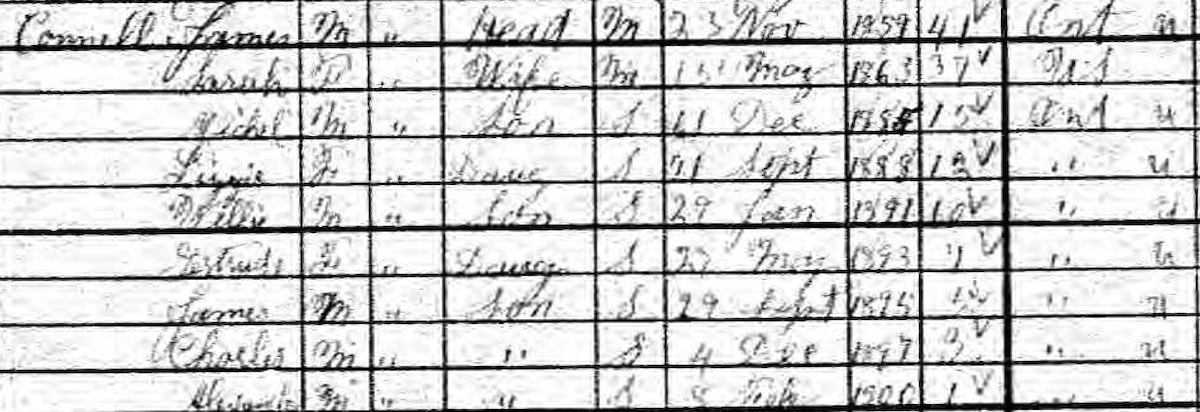

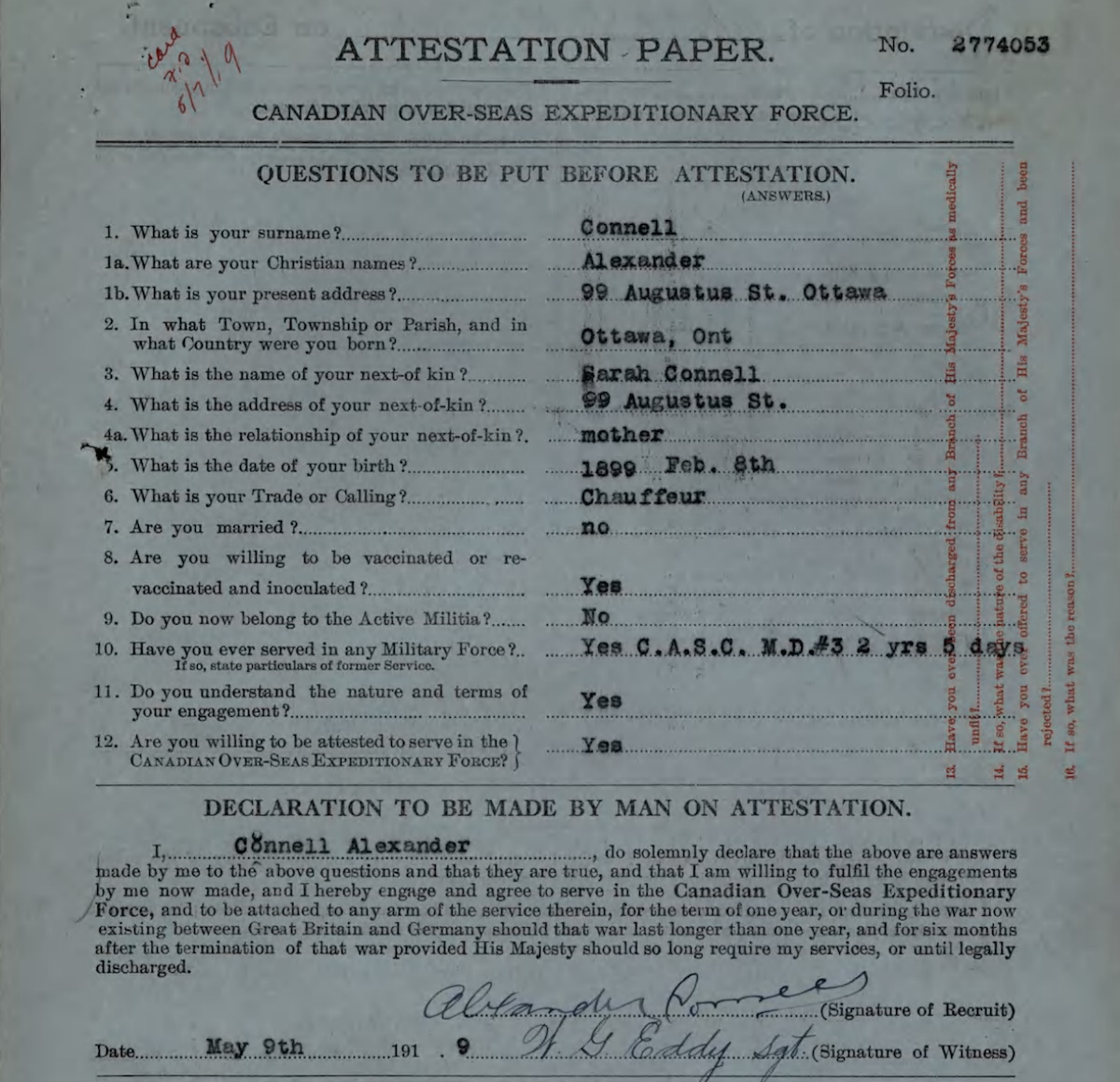

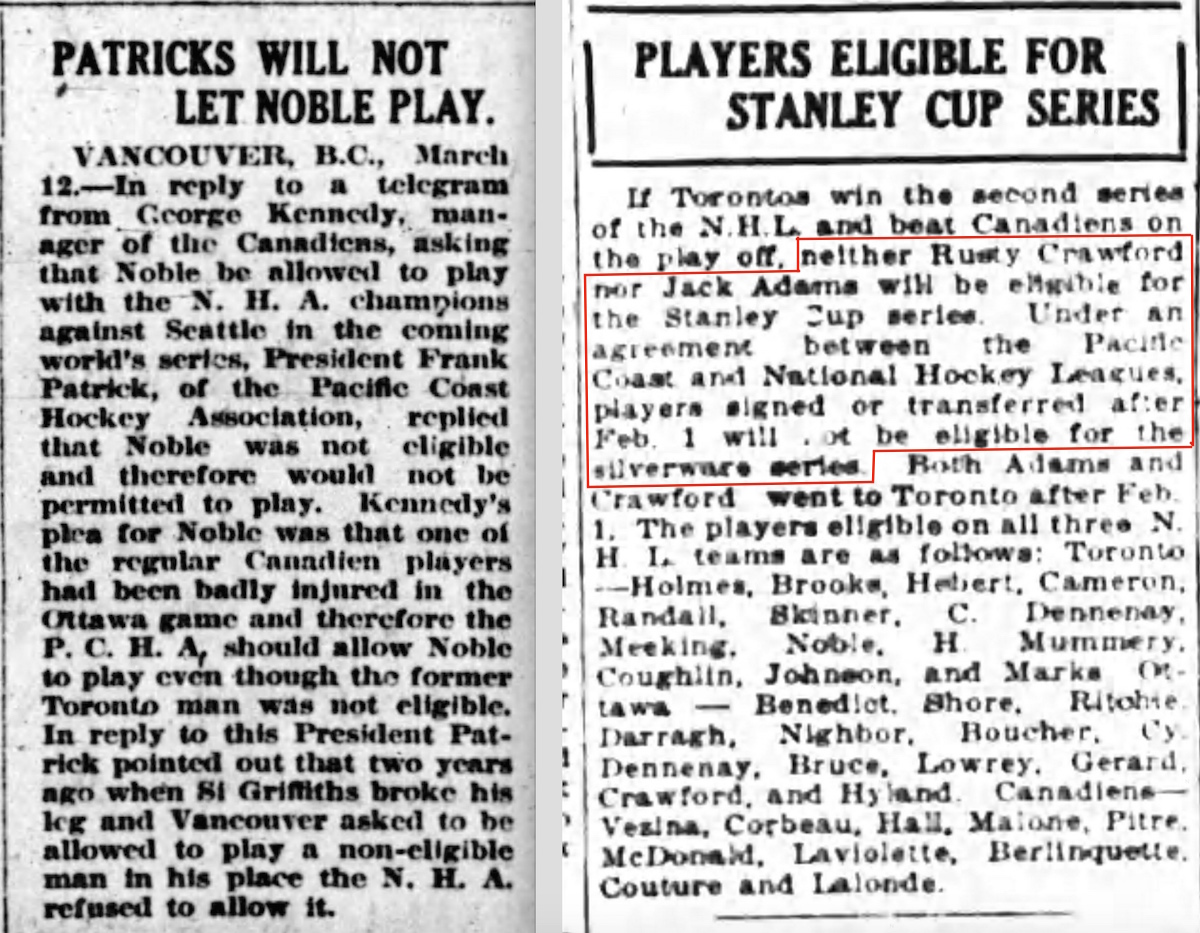

Pronouncements from the Stanley Cup Trustees, The Globe,

Toronto, March 2, 1908 and The Ottawa Journal, February 27, 1909.

In March of 1908, towards the end of the 1907-08 season, the trustees in charge of the Stanley Cup made an announcement. Beginning the following season, they would no longer consider any player eligible to play in a Stanley Cup challenge if they had appeared on more than one team during that season. Transactions in those days were usually more like free agent signings than our modern concept of trades, but in a sense, the trustees established hockey’s first trade deadline as the day before the start of the 1908-09 season.

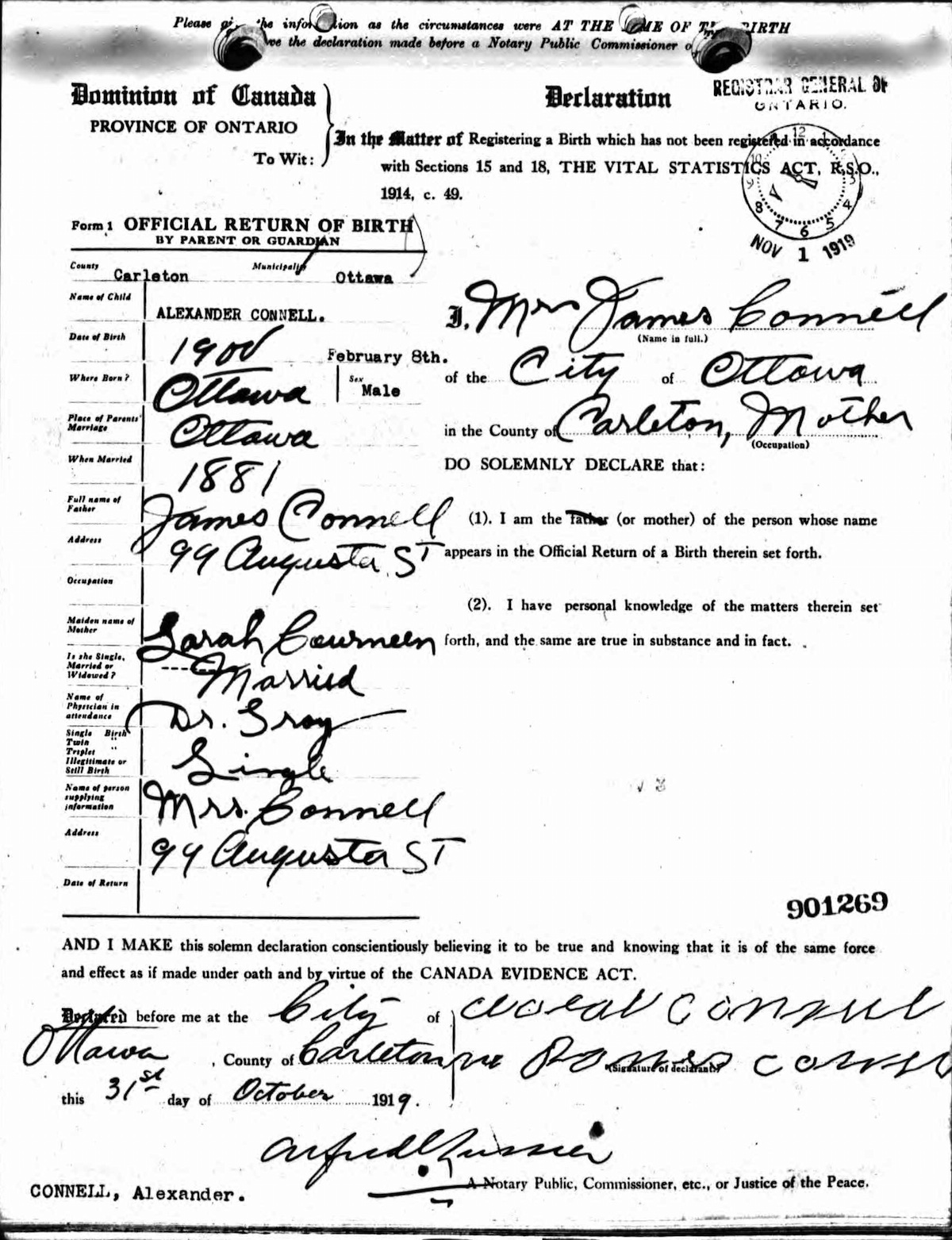

Despite the trustees’ announcement, Edmonton’s pro team loaded up with ringers for a Stanley Cup challenge against the Montreal Wanderers in December of 1908. Edmonton had won the championship of the Interprovincial Professional Hockey League (a three-team loop with clubs based in Alberta and Saskatchewan) in 1907-08, but – as was common in this era – their Stanley Cup challenge was put over until the start of the next season. Newspapers mocked Edmonton’s signing spree, but the Stanley Cup trustees realized that in a case like this – knowing that contracts in this era only bound a player to his team for one season – it would be impossible and unreasonable to expect Edmonton to use all the same players from 1907-08. In fact, compelling the team to re-sign them all would give the players too much leverage in contract negotiations.

As a result, Edmonton’s ringers were allowed to play. The team lost anyway … and when new challenges for the Stanley Cup came in during the 1908-09 season, the trustees made it clear they would only allow players who’d been acquired by their teams prior to January 2, 1909 – the aforementioned start of the 1908-09 season.

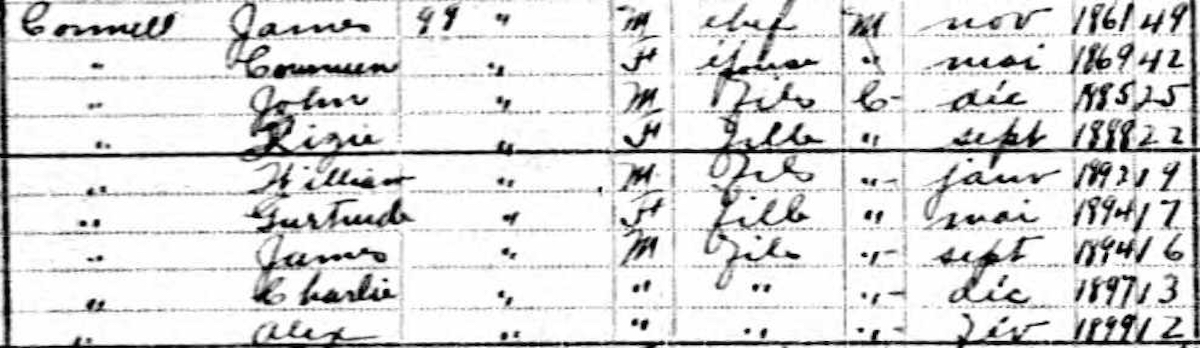

Agreement between the NHA and the PCHA, The Winnipeg Tribune, September 5, 1913.

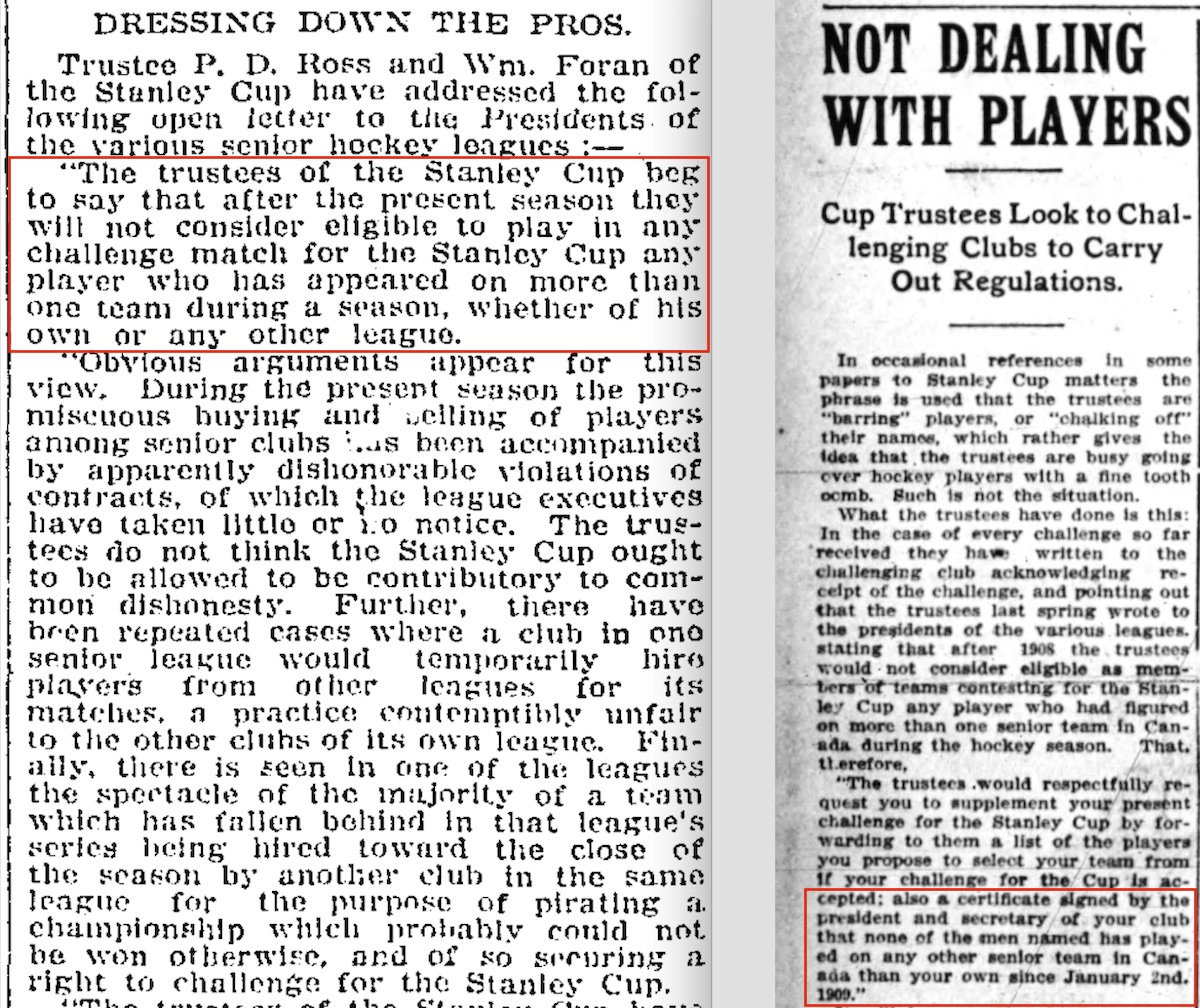

The trade deadline in hockey became more formalized before the 1913-14 season. By then, hockey had produced two major professional leagues that ranked above all others – the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) and the Pacific Coast Hockey Association. On September 4, 1913, the two leagues signed a deal to create a Hockey Commission to oversee the pro game. (A similar deal would later be reached with the Maritime Professional Hockey League, but that outfit was nearing its end.)

The NHA and PCHA agreed to arrange a postseason championship between their two leagues. The teams in both leagues were free to trade or purchase players, but no player acquired after February 15 could be used by his new club. This agreement was ratified by the two leagues in November, and the Stanley Cup trustees soon agreed that the Stanley Cup would be offered as the prize for the championship series.

Traded too late to be eligible, The Ottawa Journal, March 12, 1917 and February 27, 1918.

The NHA and the PCHA signed a new deal in the fall of 1916, which continued on after the NHL was formed in 1917. In this agreement, the trade deadline was moved to February 1. Players acquired after that date would be allowed to play in league games and playoffs with their new team, but they would not be eligible to compete in the inter-league series for the Stanley Cup. Hockey historians know the February 1 deadline was in force during the first NHL season because Toronto wasn’t permitted to use Rusty Crawford or Jack Adams (who’d both been acquired after February 1) in the 1918 Stanley Cup series with Vancouver. The same rule had made Reg Noble ineligible to play for the NHA’s Montreal Canadiens against Seattle in 1917.

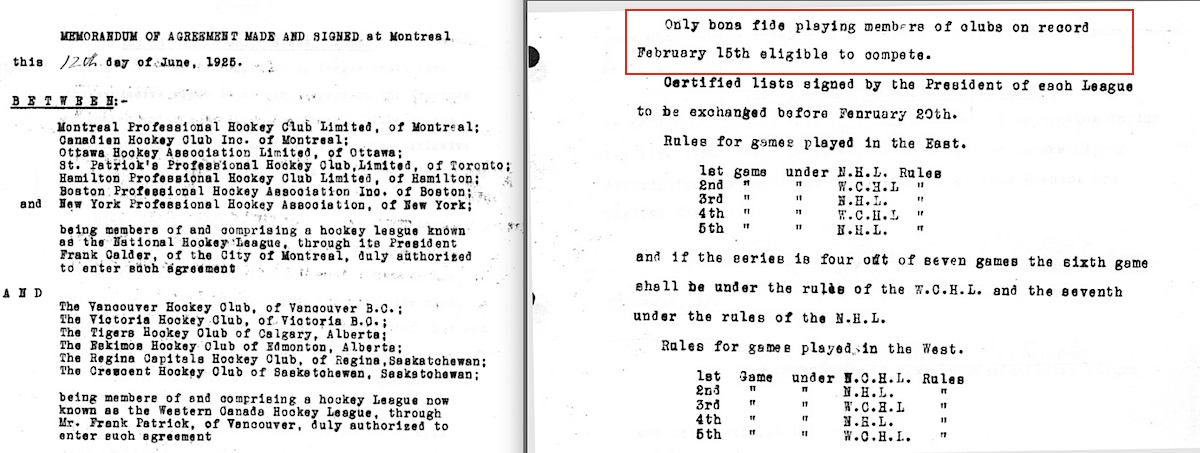

Agreement between the NHL and PCHA, dated September 24, 1921.

In 1921, the NHL signed a new deal with the PCHA which moved the trade deadline back to February 15. That date was maintained when a new agreement was signed with the Western Canada Hockey League in 1925.

Agreement between the NHL and WCHL, dated June 12, 1925.

The collapse of pro hockey out west in 1926 left the NHL as the only league competing for the Stanley Cup in 1926-27. The first mention I could find in newspapers of an NHL-only “trading deadline” doesn’t appear until 1935, but nothing about that story gives any indication that this was a new rule. So it seems very likely that the NHL had continued to enforce a trade deadline as a way to prevent contending teams from loading up on star players from weaker teams before the playoffs.

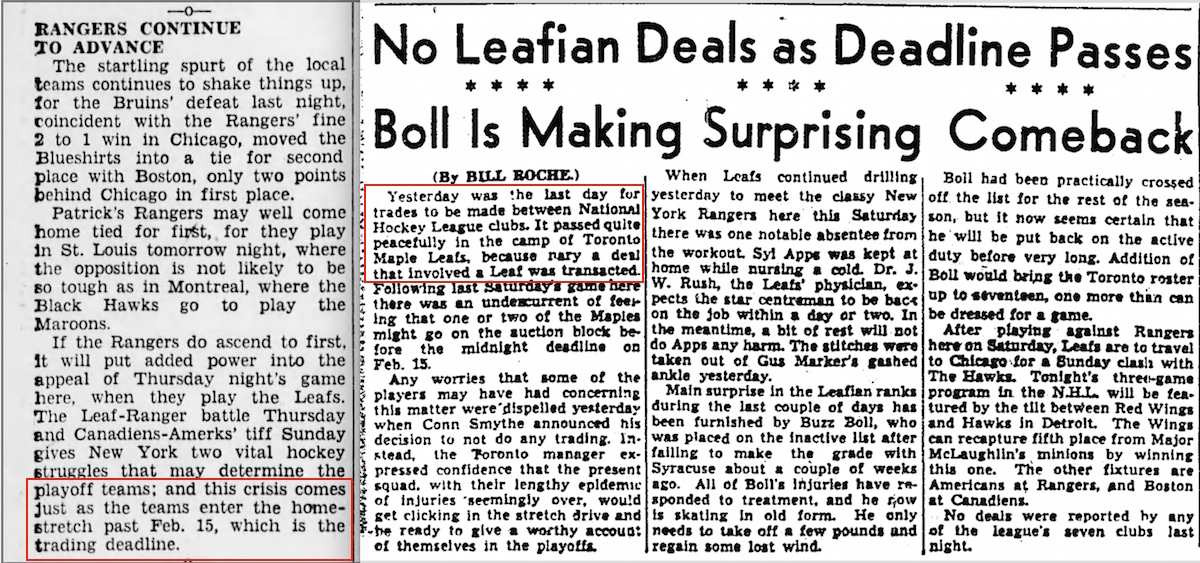

Reports on the “trading deadline” in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

February 11, 1935 and Toronto’s Globe and Mail, February 16, 1939.

Stories about the “trading deadline” continue to appear during the 1940s and ’50s, and become more prominent in the 1960s. (The Maple Leafs’ big deal for Andy Bathgate in 1964, and Toronto’s trade of Frank Mahovlich in 1968, were both made just before the deadline.) Over the years, the date jumped around as seasons got longer, but it seems that Trade Deadline Day has been part of the NHL since the very beginning.

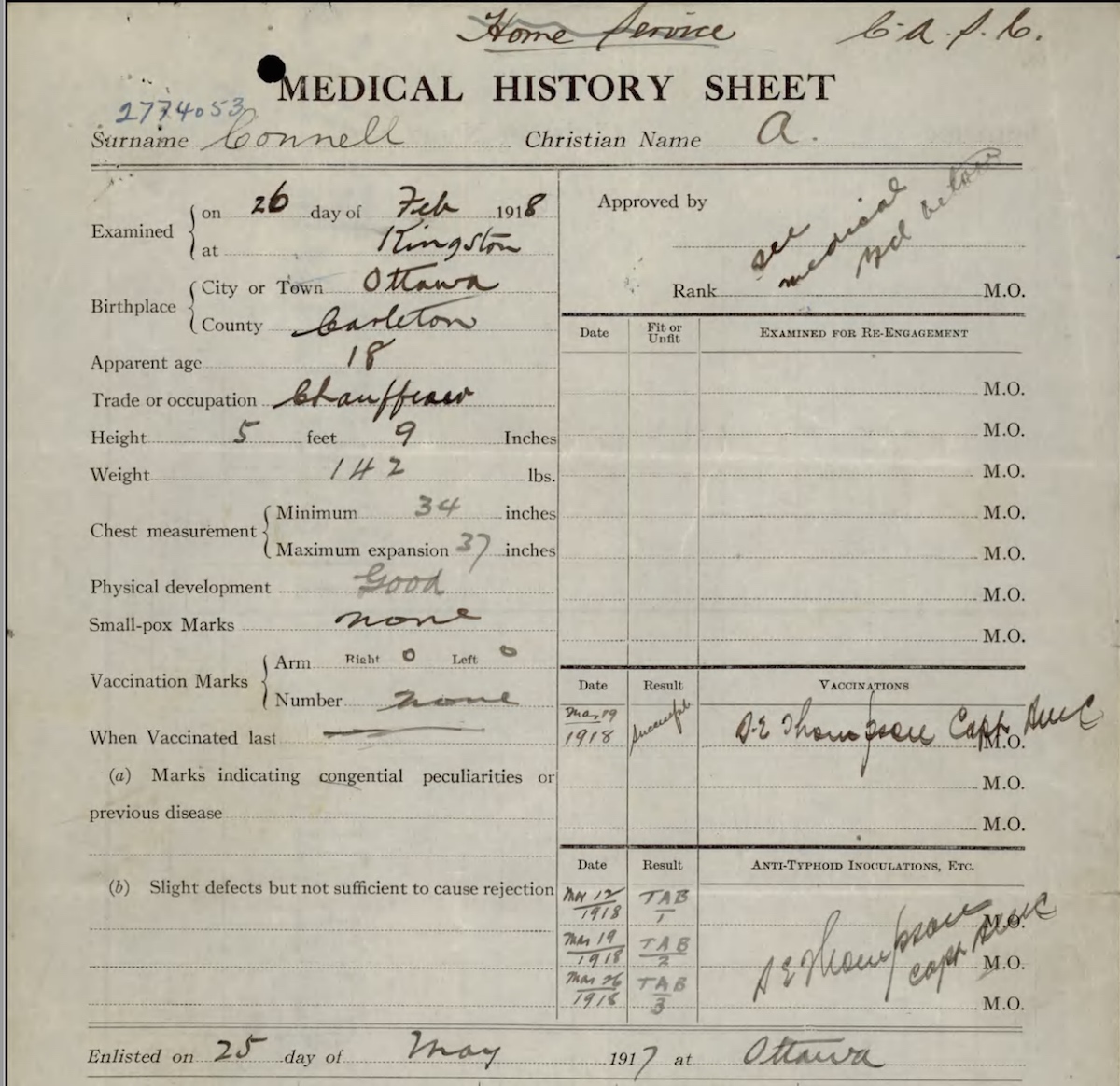

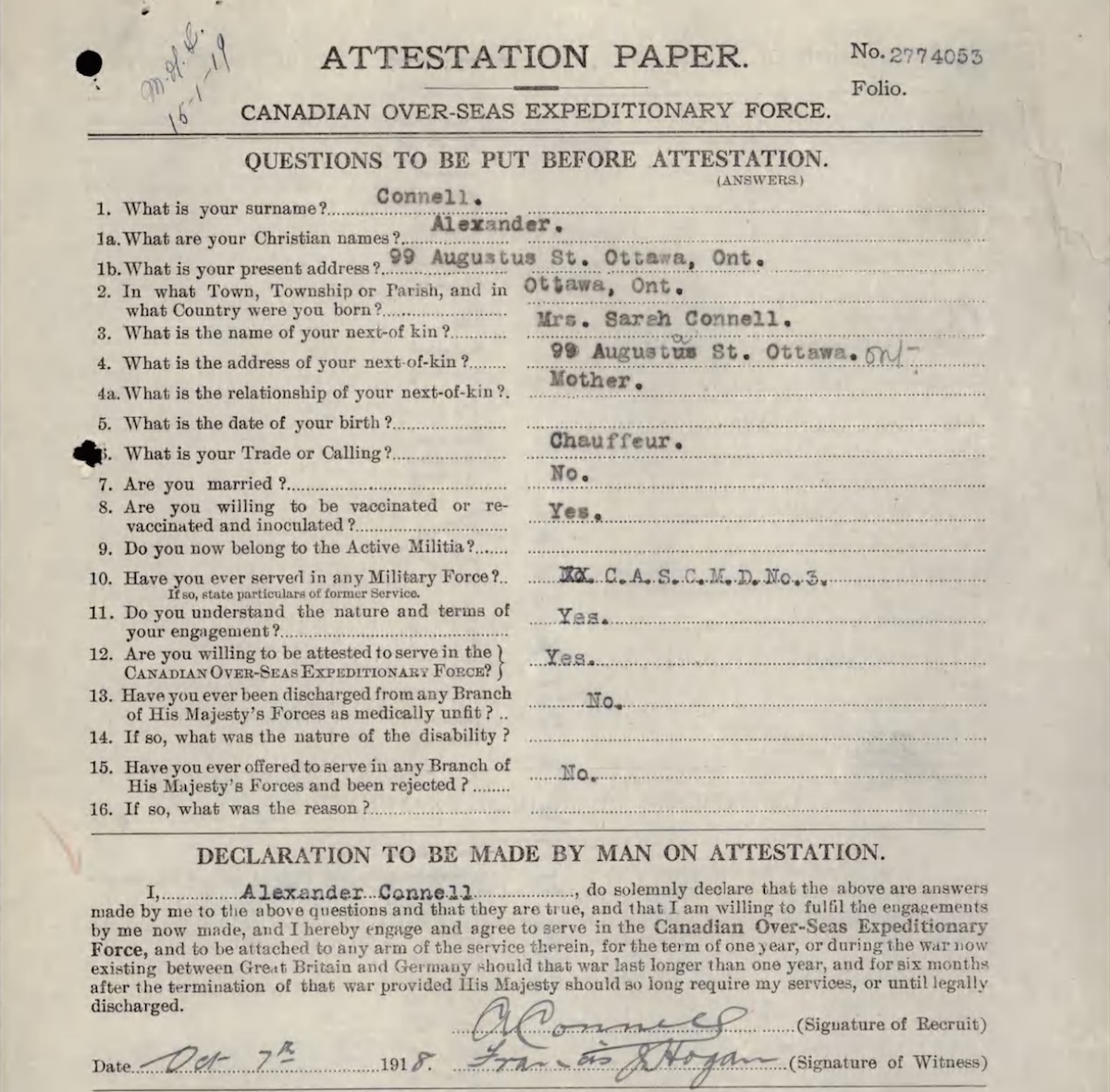

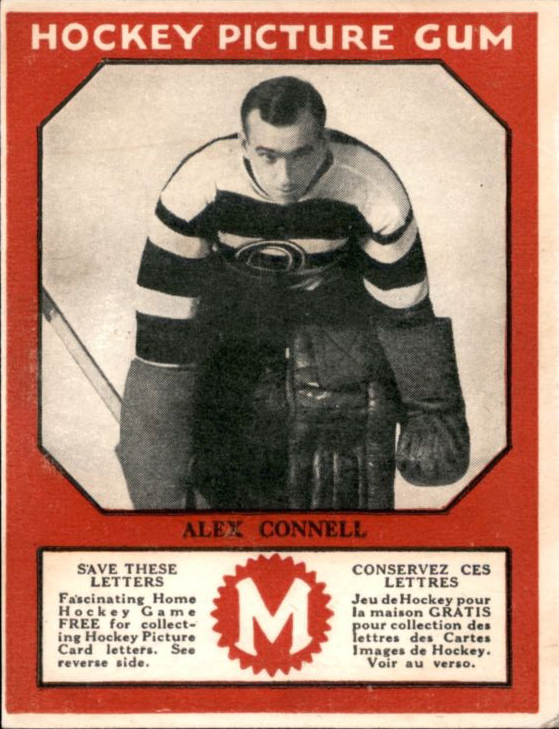

Alec Connell’s debut with the Senators on November 24, 1924 earned a note

Alec Connell’s debut with the Senators on November 24, 1924 earned a note