Back to hockey history this week. And, let’s be honest, a bit of book promotion too.

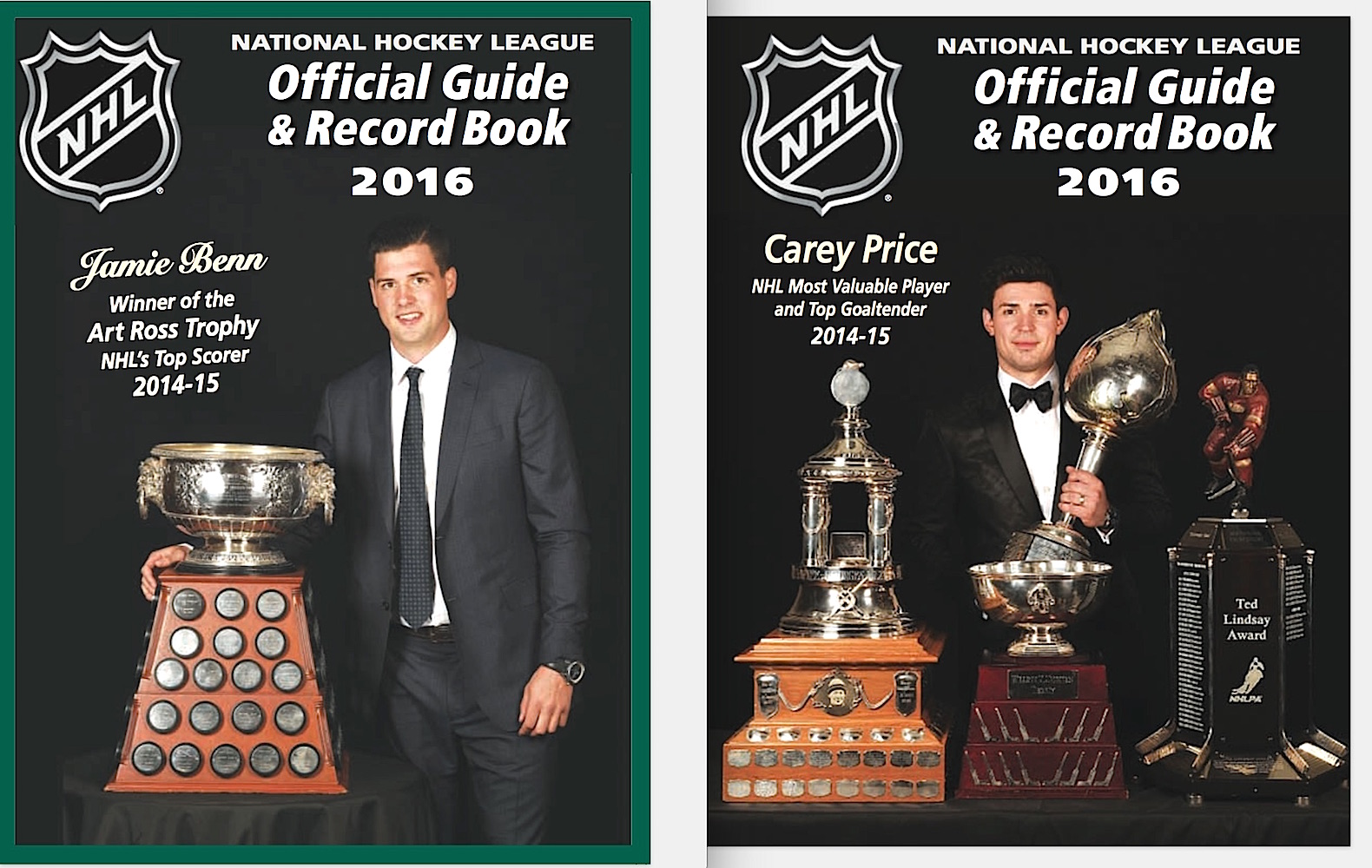

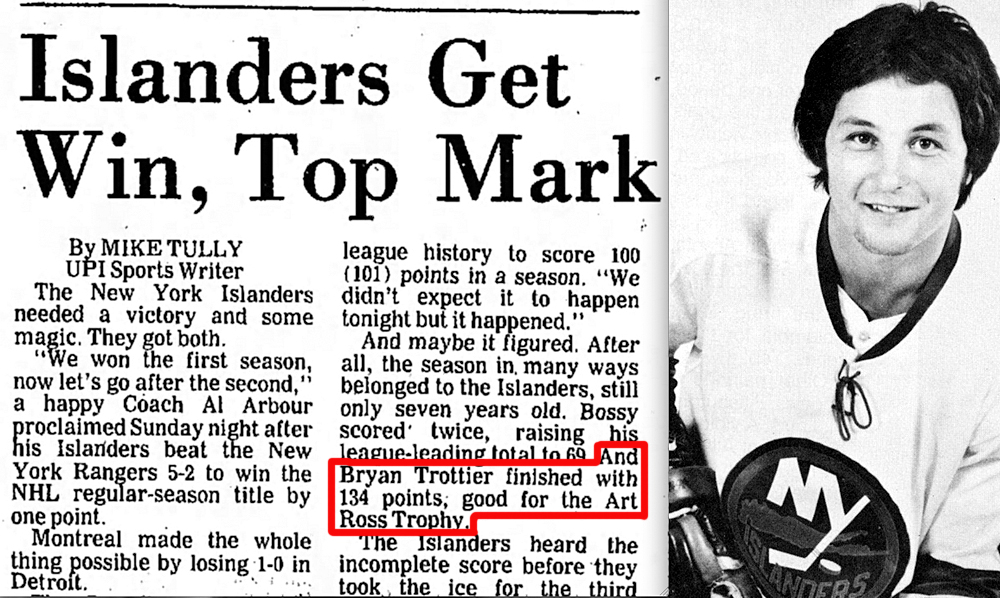

When I was pitching my new biography of Art Ross, I kept saying to publishing people that Ross’s name was one that every hockey fan already knew … even if they didn’t know why. That’s because, ever since the 1947-48 season, the player that leads the NHL in scoring has been rewarded with the Art Ross Trophy. As I say very early in my book, Art Ross was so much more than just a name on a trophy. But what if the NHL scoring trophy had a different name?

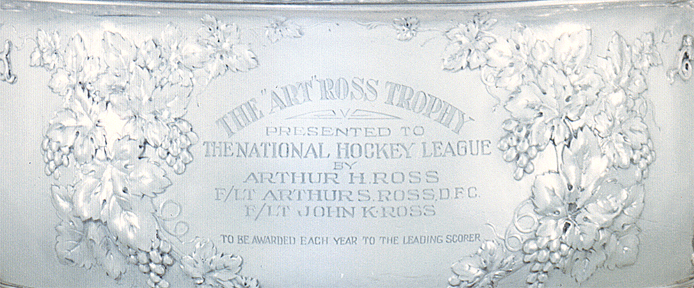

My experience has been that most people think the Art Ross Trophy was created by the NHL to honour Art Ross. That’s not true. None of the NHL’s early trophies were actually created by the league. Each piece of silverware was purchased independently by an individual donor who wished to turn it over to the NHL. Even the Vezina Trophy, which WAS named for Canadiens goaltender Georges Vezina, was purchased by the owners of the Canadiens and donated to the league in 1926 to honour Vezina after his career, and then his life, was cut short by tuberculosis. Previously, the Hart and Lady Byng, and later the Calder, were all originally named for the men and women who purchased those trophies and donated them to the NHL. Like those trophies, the Art Ross Trophy was actually purchased by Art Ross, along with his sons Arthur Stuart Ross and John Ross, and that’s why it bears his name to this day.

Still, it’s unclear why the NHL went more than 20 years after the donation of a trophy to recognize the league’s best goaltender before someone finally chose to honour the league’s best scorer. Charlie Conacher, a two-time NHL scoring champion (and five-time goal-scoring champion), certainly thought it was odd.

In a daily column he wrote for Toronto’s Globe and Mail newspaper during the 1936-37 season, Conacher noted on February 12, 1937: “It is the ambition of every forward to make his goals and assists reach a larger total than that of any of his rivals. I know I was always under the impression that there was a trophy for realizing this ambition until I finally was successful. Then, the year I led the league I found that with the honour went no prize that I could keep for later years.” In his column a day later – while admitting that the NHL’s maximum salary of $7,000 was a lot of money (!!!) – Conacher added that, in addition to a trophy, a cash bonus for winning the scoring title would be nice too.

Over the next few weeks, Conacher responded to many letters he received commenting on his trophy and bonus suggestion. Most fans were against it. Some felt it would encourage selfish play (to which Conacher replied that assists were worth as many points as goals). Others felt players deserved no extra award or incentive for doing what they were already paid to do (but “winners of the Vezina, Hart and Lady Byng Trophies are only doing their duty too,” countered Conacher in his February 18 column). There were those who supported Conacher’s idea, but felt that such a trophy should be awarded to the top-scoring line, or the top-scoring team, instead of an individual player.

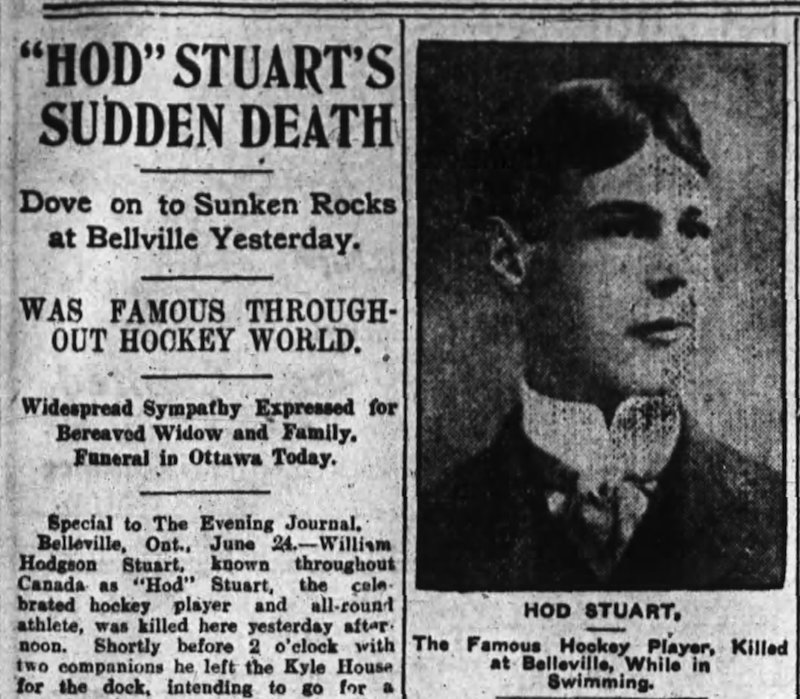

Nearly a month later, in his March 16, column, Conacher printed the contents of a letter he received from a Toronto man named Bob Mitchell: “I have read a great deal about your thoughts toward having a trophy for the leading scorer of the NHL…. Wouldn’t it be a fitting tribute to the late Howie Morenz if the NHL Governors donated a trophy called the Morenz Cup to be presented to the leading scorer of the NHL each season.”

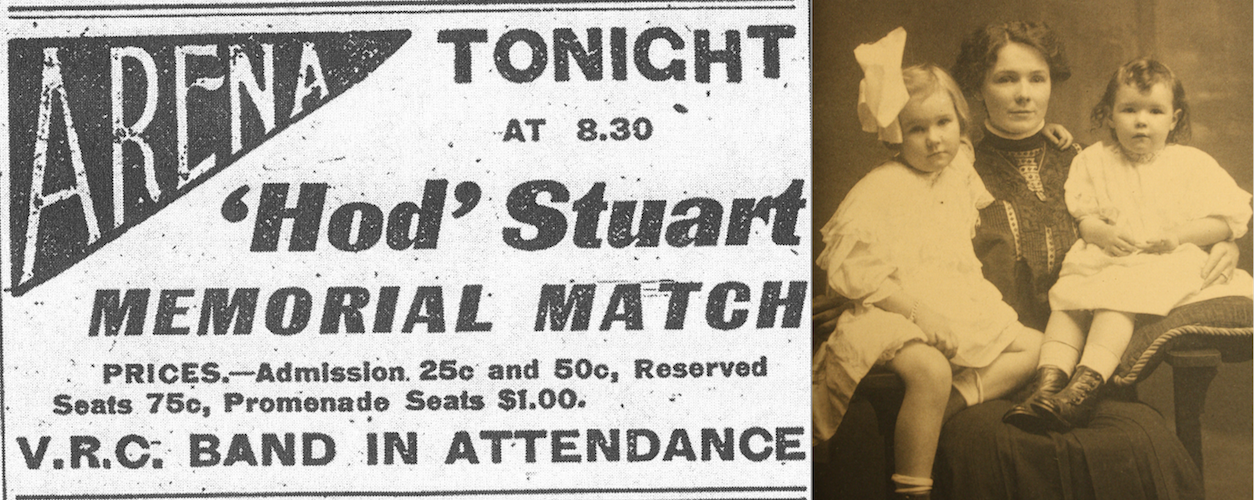

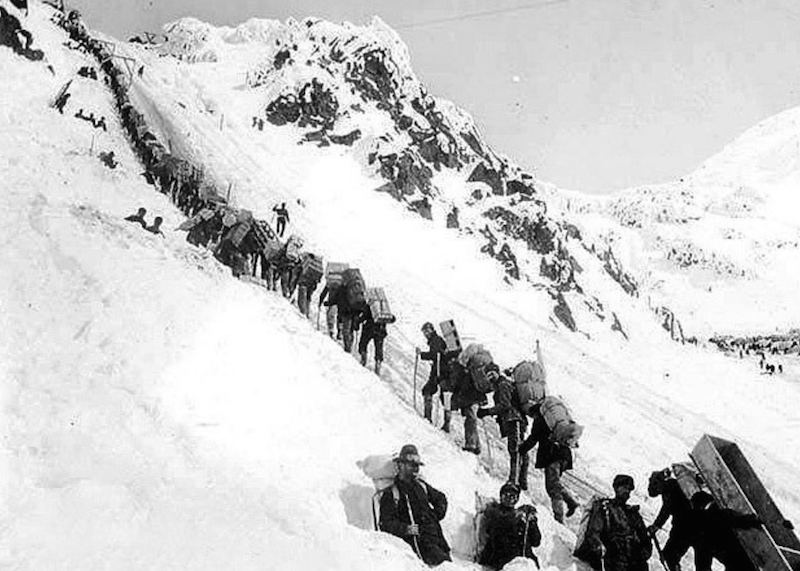

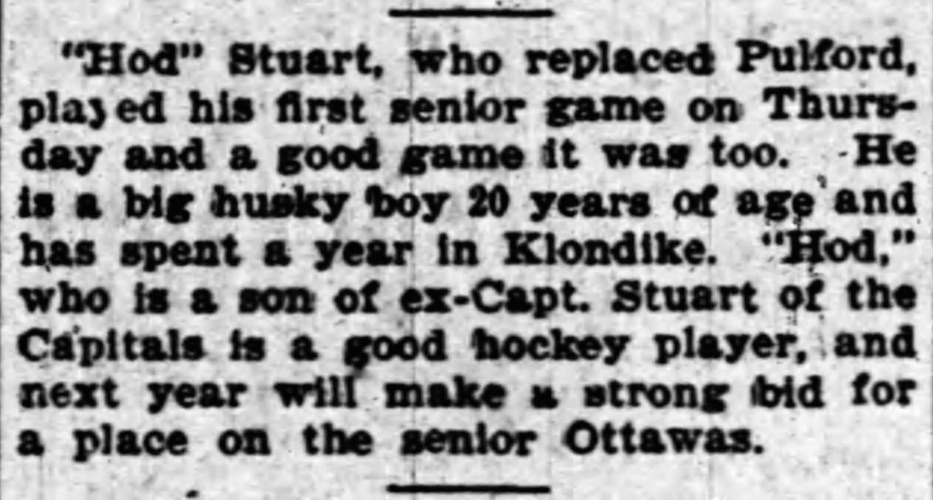

Morenz had passed away on March 8, 1937, several weeks after suffering a career-ending broken leg in a game on January 28. Conacher had been advocating for a benefit game for Morenz (and a players injury fund too) since his February 15 column and was pleased to report before noting Mitchell’s suggestion that the Governors had committed themselves to such a game – though it would not take place until November. None of the NHL Governors, however, ever stepped forward with a Morenz Cup. It would take until the 1946-47 season before the NHL finally awarded a $1,000 bonus to the NHL scoring leader. It was another year until Art Ross finally donated a scoring trophy.

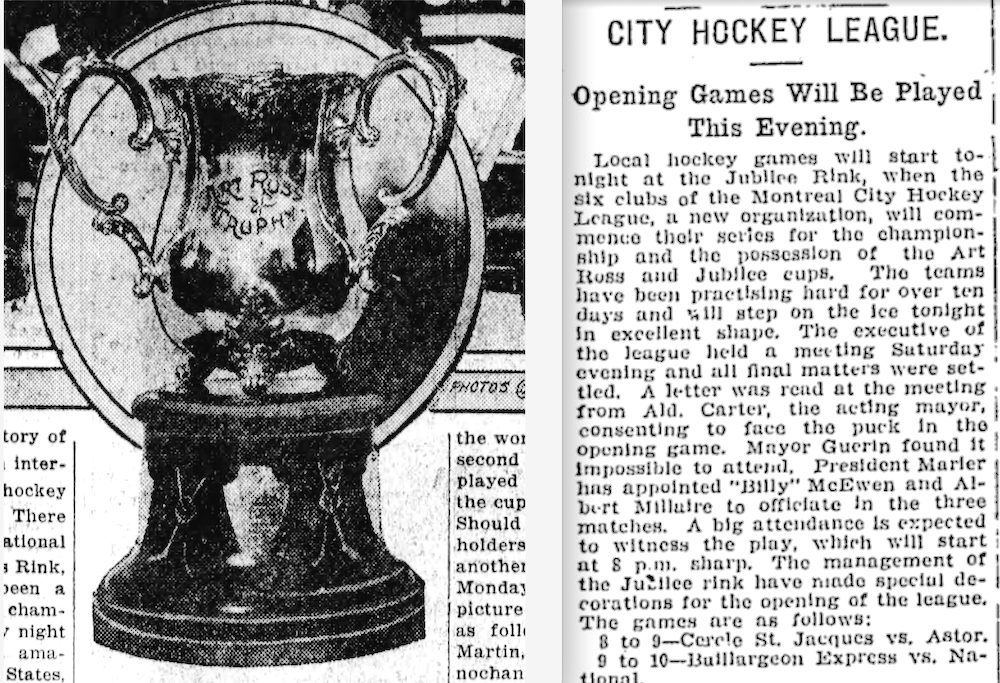

This is the original Art Ross Trophy, purchased by Art Ross in 1910 for competition in the Montreal City Hockey League. A few years later, it became an international amateur award. Although the engraving clearly says Art Ross Trophy, this old mug is usually referred to as the Art Ross Cup.