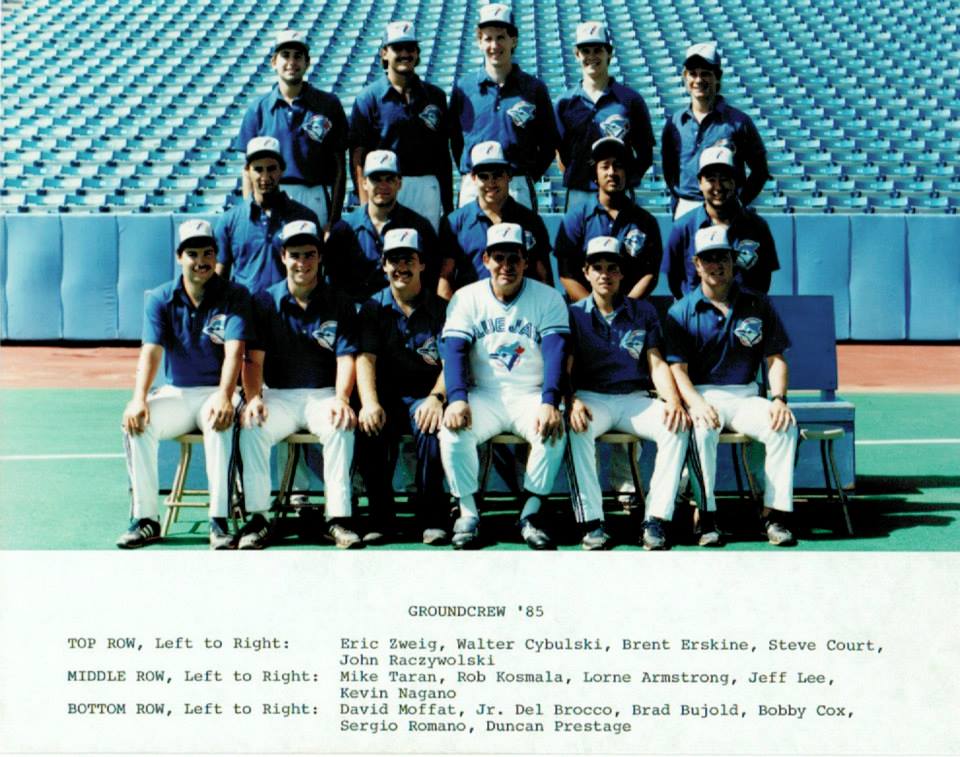

I attended the Blue Jays’ home opener on Monday, running my streak to 39-for-39 in franchise history. (Even when they were rained out in 1980, I skipped my last class to attend the 4 pm first game two days later.) Of all the books I’ve worked on, my favorite would be when we did the Toronto Blue Jays Official 25th Anniversary Commemorative Book at Dan Diamond & Associates. It’s hard to believe it was so long ago.

Our book came out about the same time that HBO released 61*, which was directed by Billy Crystal. He talked a lot about what a thrill it was for him to tell this story of his childhood heroes. Well, Billy Crystal got to worship Mickey Mantle, and Roger Maris, and Whitey Ford when he was a kid … but I’ve been watching for the ENTIRE HISTORY of the team I cheer for. Still, for this story, I’m borrowing from Billy’s team … though from a lot earlier than he remembers.

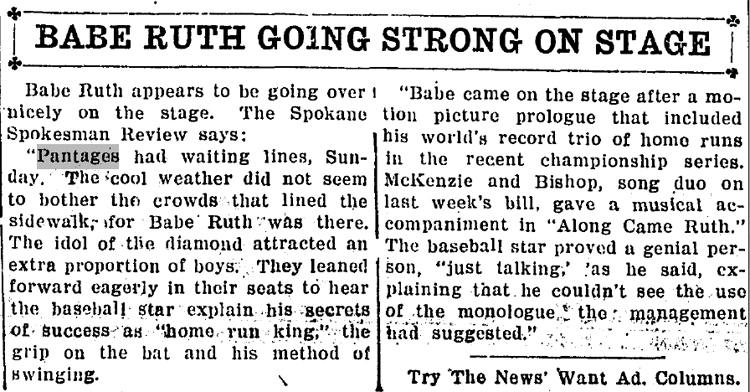

Recently, I came across Mark Truelove’s web site candiancolour.ca which displays digitally colourized historical Canadian photographs. It’s AMAZING. My only criticism is there aren’t enough pictures! (I imagine that’s because it takes time for him to do them so well.) The picture below is one of two on Mark’s site featuring Babe Ruth, and it got me wondering what he was doing on stage at the Pantages Theater in Vancouver on November 29, 1926.

On stage with Babe Ruth in Vancouver is mayor L.D. Taylor as catcher and

Chief of Police Long as umpire. For a larger image, see Mark’s web site.

For another original shot of Ruth on stage, see the Vancouver Archives.

Babe Ruth had had a terrible season by his standards in 1925. That was the year of “The Bellyache Heard ’Round the World” when he arrived at spring training horribly overweight and eventually spent several weeks in hospital with a stomach ailment that has never really been explained. Back in shape for 1926, Ruth rebounded to hit .372 with 47 homers and 146 RBIs.

The Yankees won the American League pennant in 1926, but Ruth made the final out in game seven of the World Series against St. Louis when he was caught trying to steal second base. At the time, this actually seemed to increase his popularity! (Ruth also hit four home runs in the series, including three in game four alone, when he may or may not have promised to hit one for hospitalized 11-year-old Johnny Sylvester, which didn’t hurt his popularity either!) After the series, Ruth went on a short barnstorming baseball tour before hitting the western vaudeville circuit.

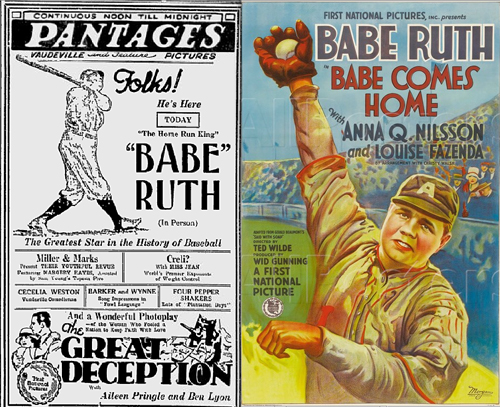

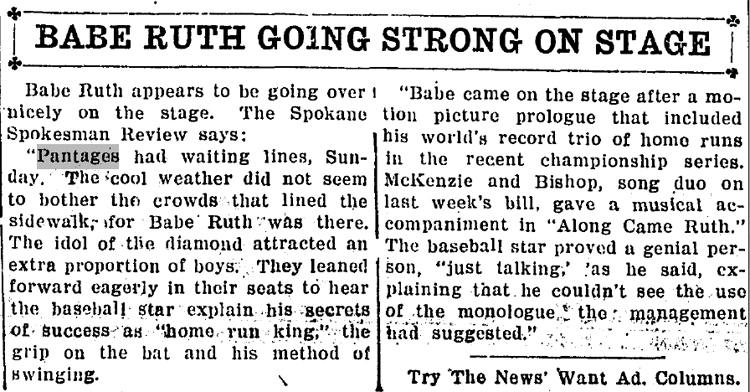

On August 31, 1926, Ruth had signed a $100,000 contract with Alexander Pantages. Others had been bidding for his services too, but Pantages, via a long-distance telephone call from Los Angeles, blew them all away with the largest offer in the history of vaudeville. It was generally reported, then and now, that the deal was for 12 weeks, though some stories that fall claimed it was a 15-week tour. Either way, it was a ton of money for a player who’d just earned $52,500 for the six-month baseball season. (Ruth would hold out for $100,000 a year for two years prior to the 1927 campaign, and eventually signed for $70,000.)

Ruth’s Pantages tour opened in Minneapolis on October 30, 1926 and made its way west, winding up in California in February of 1927. He seems to have spent several days in most of the cities he visited. Basically, Ruth went on stage, recited a somewhat fictionalized story of his life, talked baseball, demonstrated his swing, and invited boys up with him for autographs. Bill Oram, writing in The Salt Lake City Tribune on July 11, 2011, quotes some of Ruth’s patter from his visit to the Utah capital in late January:

“Mr. Dunn made a pitcher out of me,” Babe Ruth relayed to his hungry audience. He was baseball’s best left-hander early in his career, and that started with the minor-league Baltimore Orioles under the watchful eye of manager Jack Dunn.

“Then he traded me the same day to another club for a batboy,” he embellished. “I was feeling pretty bad in the clubhouse that day when I thought it over. But I figured I could do Mr. Dunn a favor. I went to him and told him the ceiling was leaking in his clubhouse.”

The audience sat rapt.

Ruth paused for the punchline to his tale. “[Dunn] said, ‘You darn boob, that ain’t a leak. That’s the shower bath!’”

In an era when most people could only expect to see him in newsreels, Ruth charmed the crowds everywhere he went. In Vancouver, he had lunch with orphans at a Children’s Aid Society home and visited a disabled boy in hospital. This seems typical of most of his stops, and in some cities he even wrote a column (or, likely had it ghost-written) in local newspapers. Not everyone was enamored of his stage performance, however. Yankee biographers Jonathan Eig and Harvey Frommer both quote Ruth’s teammate Mark Koenig as calling his set, “boring as hell.” Sixteen-year-old Doris Bailey of Portland, Oregon (whose “Doris Diaries” have been published and appear online) thought Ruth was “not so much to rave about. Terribly conceited.”

Towards the end of the tour, Ruth was arrested in San Diego on January 23 because it was said that by calling up boys on stage with him so that he could sign autographs he had violated California’s Child Labor Laws! Regardless, kids stormed the stage in Long Beach the following night, and Ruth was later acquitted of the charges.

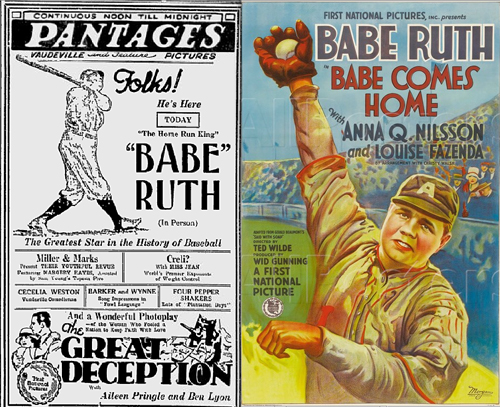

Before leaving California, Ruth lingered a little longer to film the movie Babe Comes Home, in which he plays a ballplayer whose love of a woman is threatened by his addiction to chewing tobacco. Soon after filming, Ruth signed his new contract with the Yankees, and though he got off to a slow start in 1927, he went on to hit .356 with 60 home runs and 164 RBIs (Lou Gehrig hit .373 / 47 / 175 and was named MVP) as the “Murders Row” team went 110-44 en route to winning the World Series.