For the last couple of years, around the start of the playoffs, I’ve done a “Stanley Cup Anniversaries” story. (If you’re curious, you can check out the links to 2015 and 2016.) I’m a little late this year, and this time I’m choosing to focus on just a single quirky anniversary story. This one is from 80 years ago in 1937.

The story begins in the spring of 1936, when the Detroit Red Wings became the last of the so-called “Original Six” teams to win the Stanley Cup. Goalie Normie Smith (who I mentioned a few weeks back in Marathon Men … And Kids Too) was a Red Wings hero that season. According to a report in the Detroit Free Press (which was picked up by a few other papers) on April 17, 1937, Smith was friendly with an ex-Canadian couple living in Detroit, a Mrs. Ida Lefleur and her husband, who were expecting a baby shortly after the Red Wings’ 1936 championship.

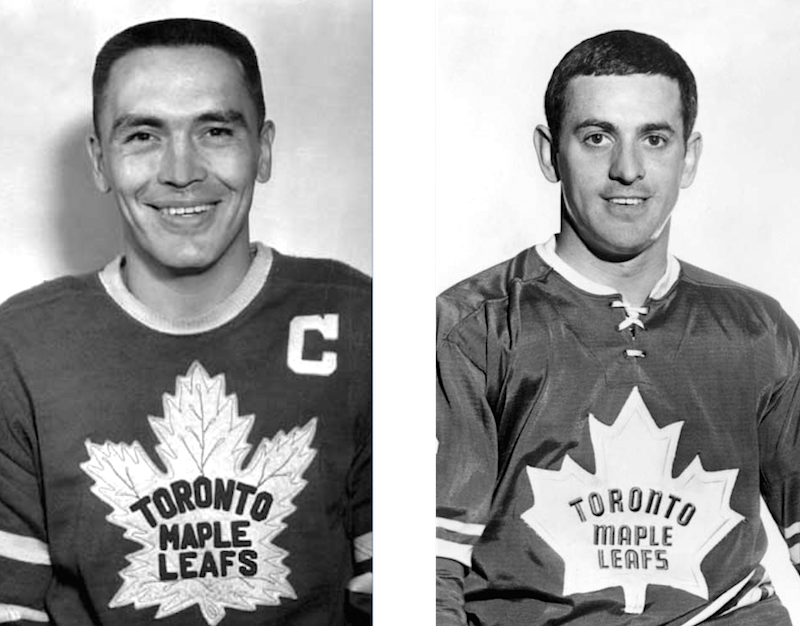

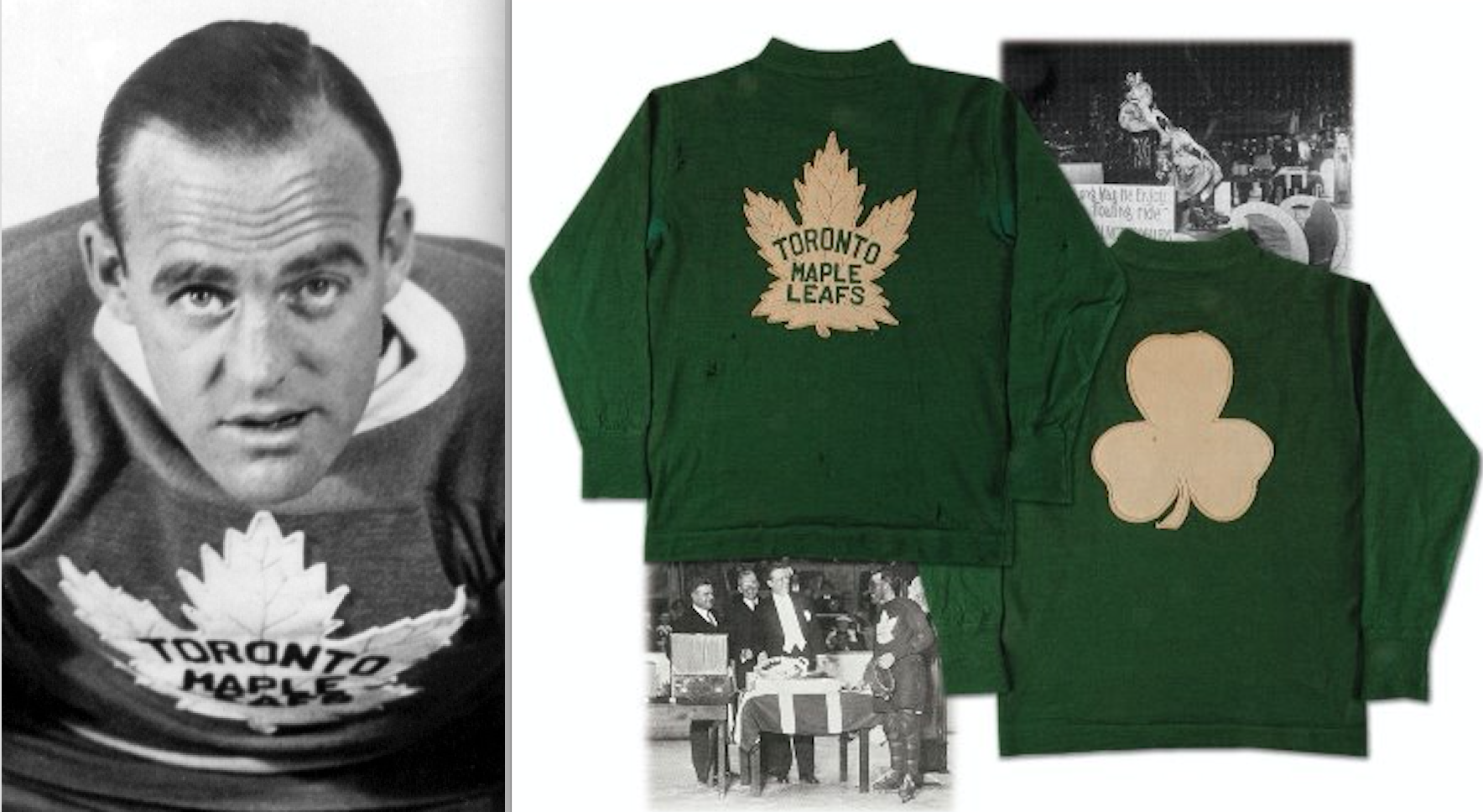

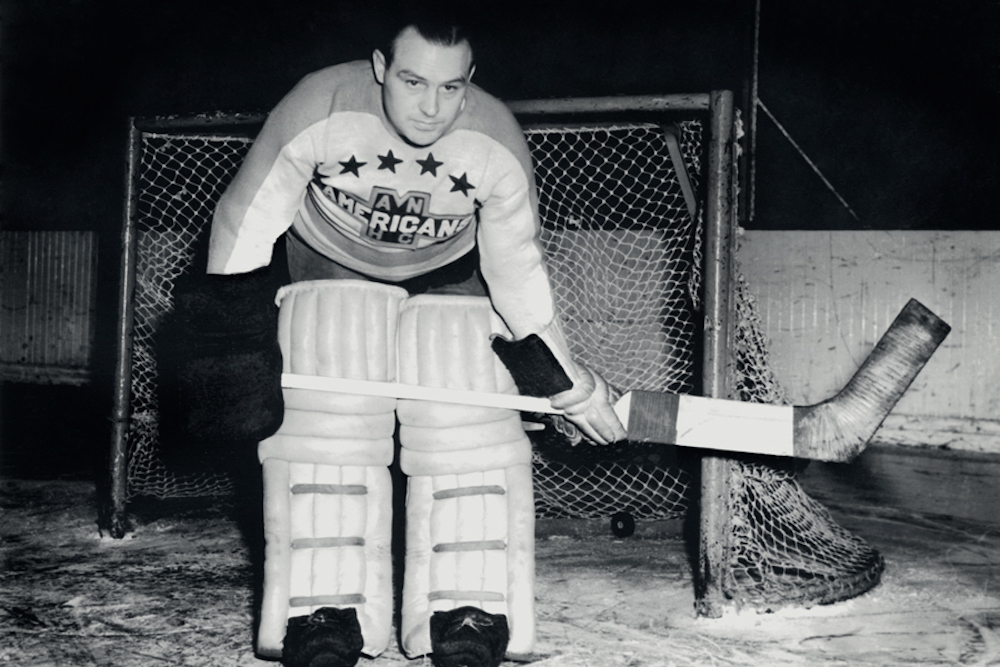

After two stellar seasons with the Red Wings, Normie Smith

was never the same after his shoulder injury in the 1937 playoffs.

“If we have a boy,” Ida told Normie, “we’ll name him Stanley after the Cup and next year the Red Wings will win the Stanley Cup again on his birthday.”

As the story goes, the boy was born on April 15, 1936 and was named Stanley Lefleur. And as it turned out, the baby’s first birthday in 1937 really did coincide with Game 5 of that year’s best-of-five Stanley Cup Final … between the Rangers and Normie Smith’s Red Wings.

Smith had won the Vezina Trophy during the 1936-37 season, but was injured in the playoffs and replaced by minor-leaguer Earl Robertson. On the day of Game 5, Smith sought his replacement. “Out near where we live is a Stanley Cup baby,” he told Robertson. “Now what you should do is go out there and take a few lucky pats on that baby’s head.”

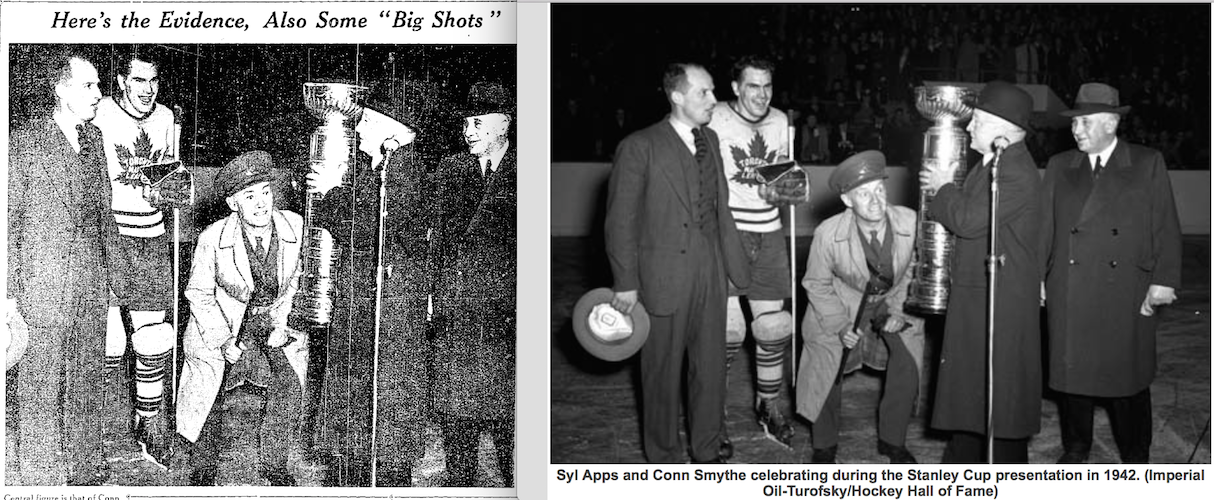

Figuring that Earl Robertson had earned a shot at the NHL,

and that Normie Smith would return healthy, the Red Wings dealt

Robertson to the New York Americans shortly after the 1937 Stanley Cup.

As the Free Press story explains, Normie Smith “will do anything for good luck.” Earl Robertson wasn’t nearly as superstitious, “but he doesn’t pass up any good luck charms.” So, “out they went to a little birthday party for Stanley and following Normie’s instructions Earl stole those few pats on the head.”

That night, Robertson recorded his second straight shutout in a 3-0 win over the Rangers as the Red Wings rallied to win the Stanley Cup. Afterwards, the injured Smith happily told of the role that he and baby Stanley had played in the comeback. “I got into the final playoffs after all,” said Smith, grinning broadly, “by getting Robbie to go out there with me.”

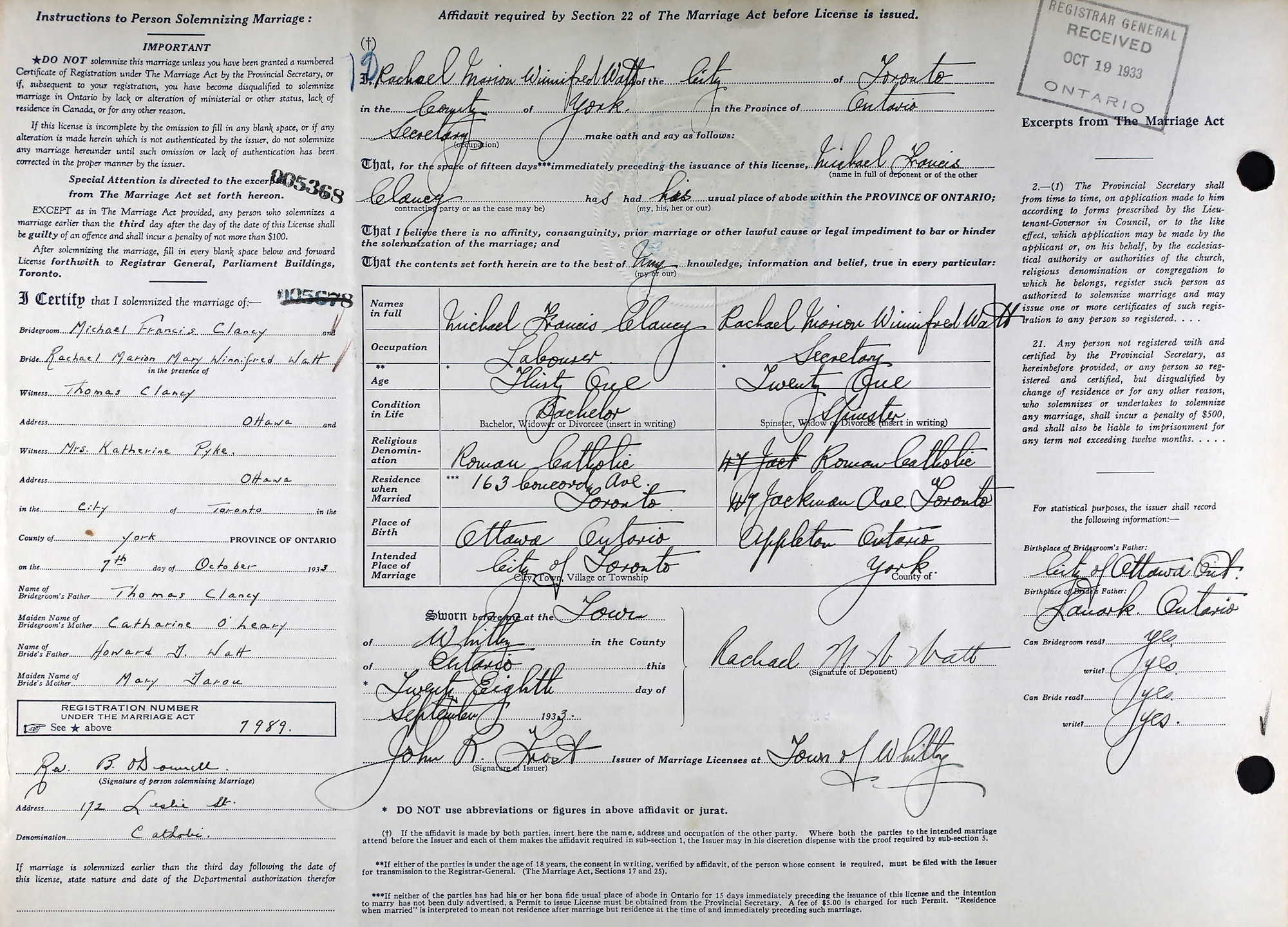

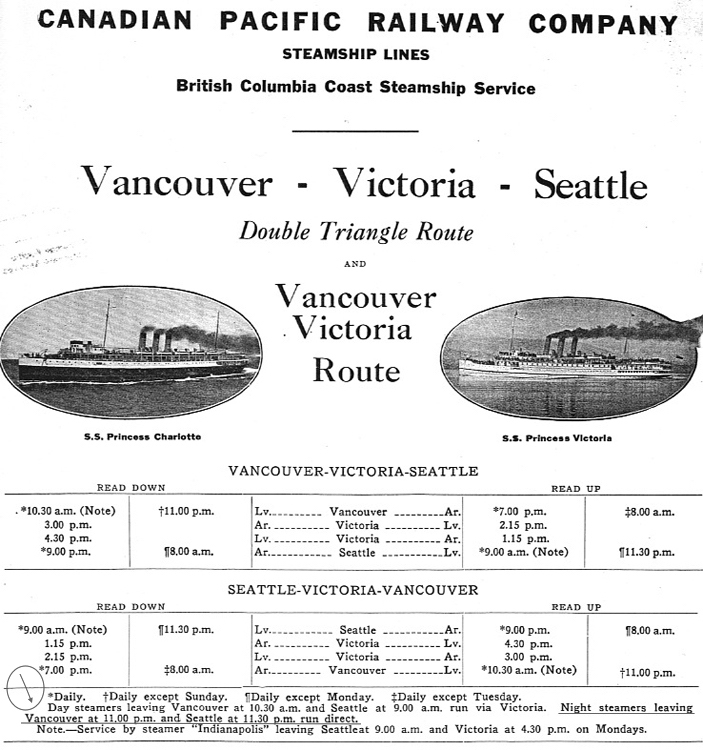

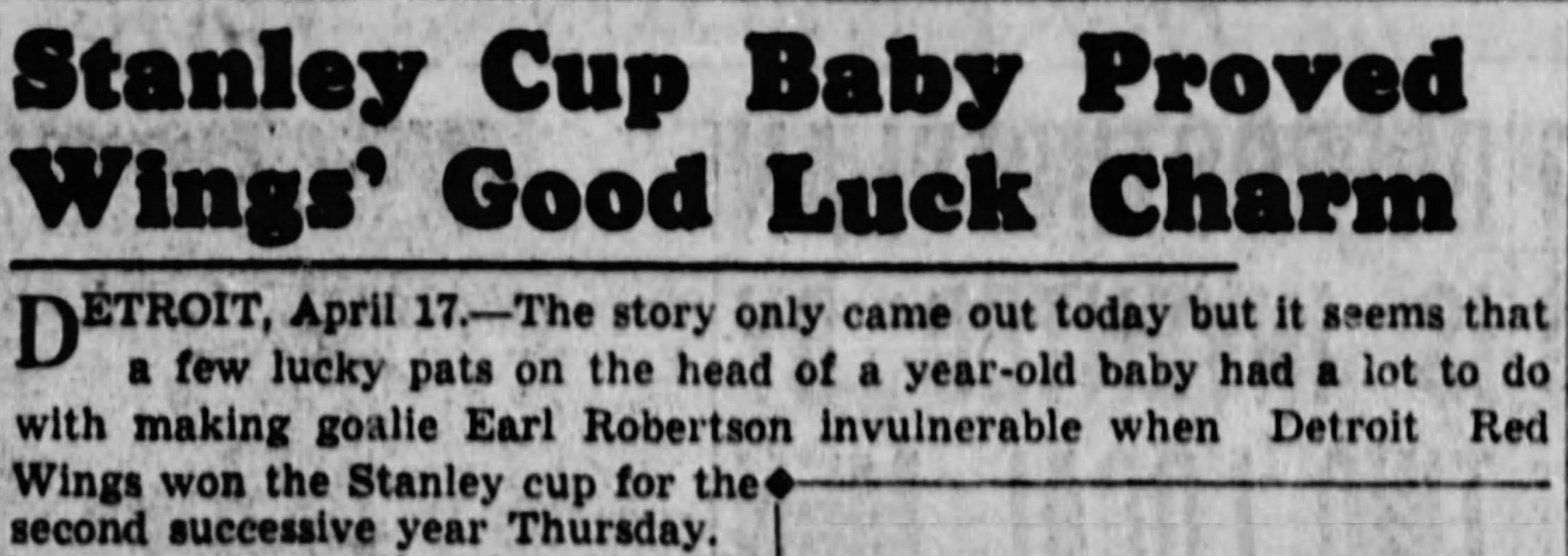

This version of the story appeared in the Winnipeg Tribune on April 17, 1937.

It’s a silly story, really, but one told with such detail that I certainly hoped it was true. So, imagine my disappointment when I went to Ancestry.com and searched for “Stanley Lefleur” born in “1936” with the mother’s name “Ida” … and found nothing.

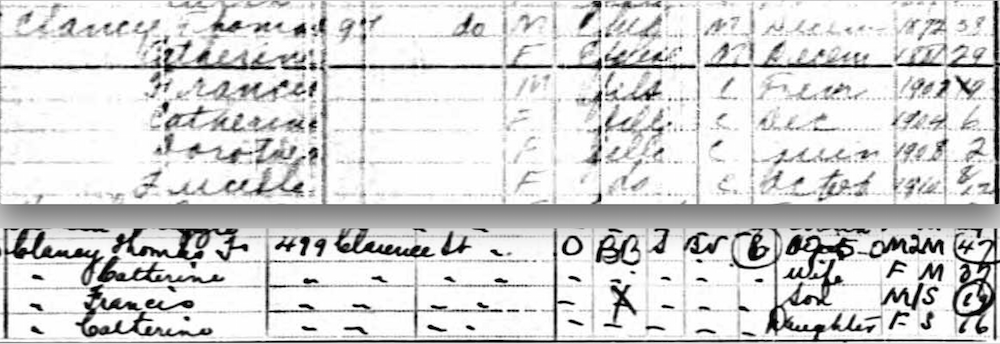

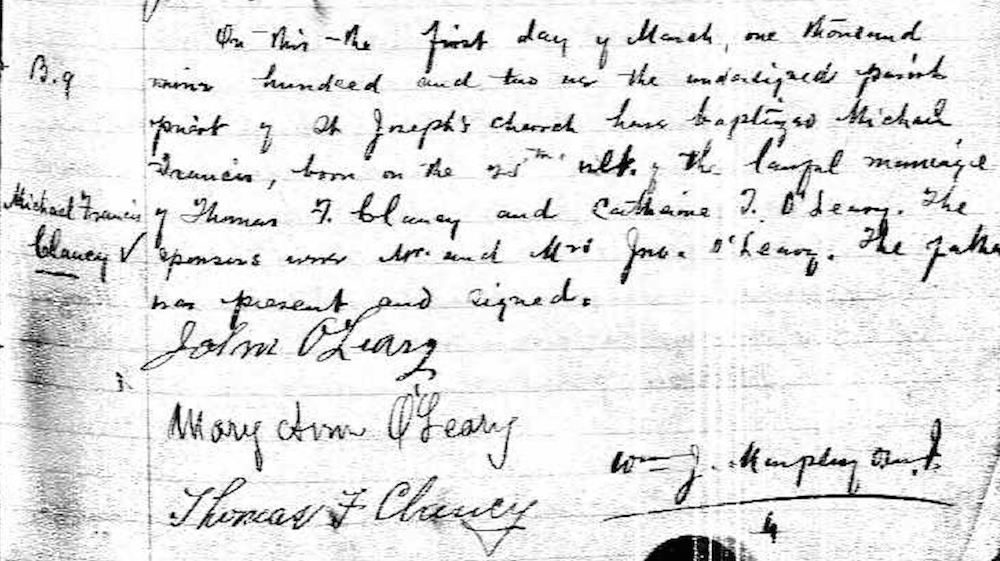

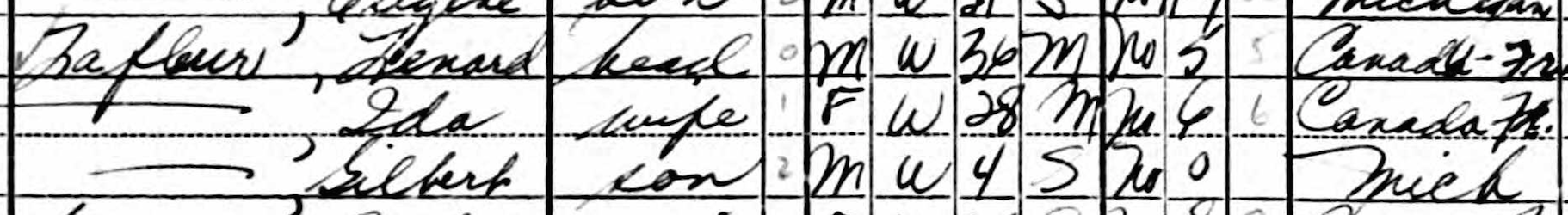

But fear not! Expanding the search a little bit, I discovered that a Gilbert Stanley Lafleur, son of Lenard or Leo Lafleur and his wife, the former Ida Bergeron (both French Canadians living in Detroit), really was born on April 15, 1936. I didn’t come across a birth certificate or baptismal record, but I did come across a record of the Lafleur family in Detroit in the 1940 U.S. Census:

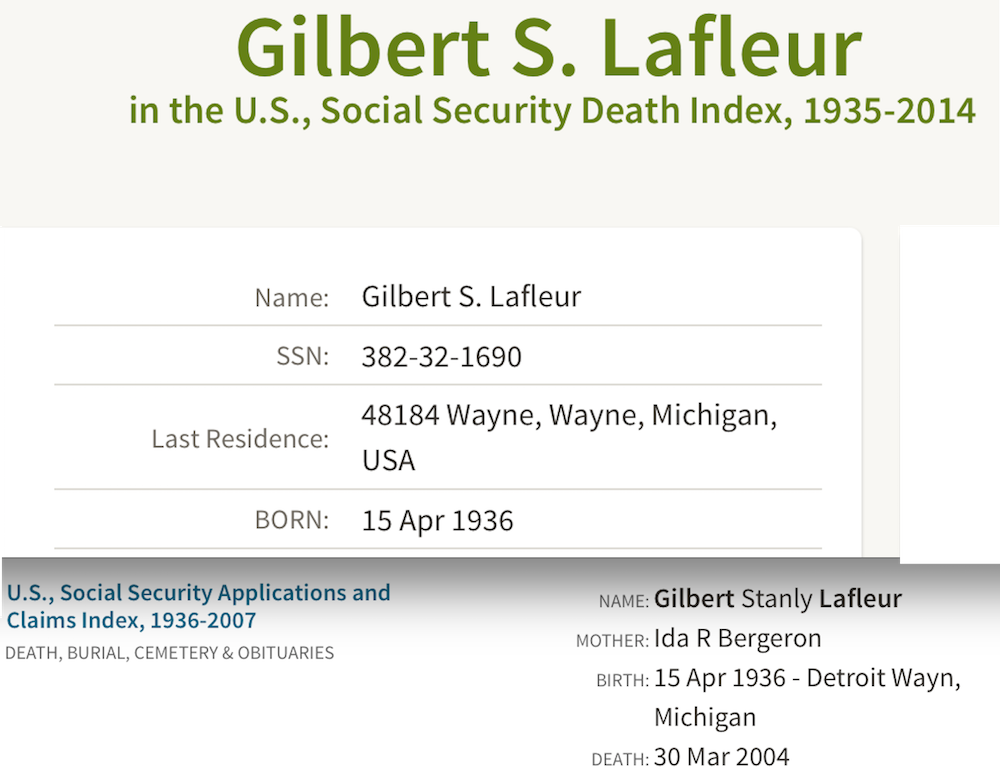

And enough Social Security records to confirm the names and dates match up.

As for the rest, I know that many old-time sportswriters never let the facts get in the way of a good story, but I’m choosing to believe this one is true!