If you’re reading this in Canada, and you’re looking to OD on hockey a day before the Super Bowl, this Saturday, Hockey Day In Canada will be bringing us its annual 13-hours of coverage. This year, the host city is Kamloops, B.C. So here’s an offbeat story from British Columbia’s hockey past.

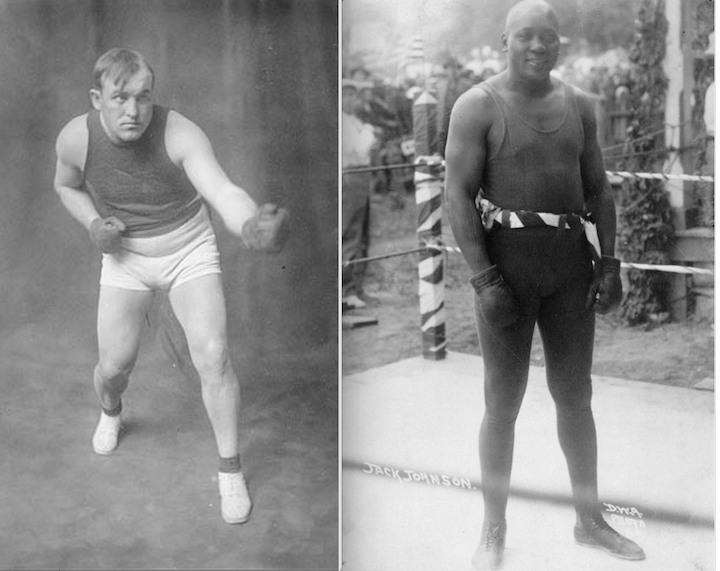

Before the NHL was formed, the Stanley Cup was a challenge trophy available to the champions of any senior provincial hockey league in Canada. Since all leagues were small and regional, the current Stanley Cup holder would be called upon to defend the Cup (much like a boxing champion or a mixed-martial arts fighter today) against challenges from champions of other leagues . Because the hockey season was so short, these challenges could occur at any time during the winter; before the season, after the season, and even in the middle of the regular season.

The most famous challenger of this early era is the Dawson City team that travelled across Canada – part of the way by dogsled – only to be crushed by Frank McGee and the Ottawa Silver Seven in January of 1905. It was rare for a challenger to defeat the Stanley Cup champion, but teams like the Winnipeg Victorias and the Kenora Thistles did pull it off.

With a population of only 6,000 people in 1907, Kenora will always be the smallest town to win the Stanley Cup. But it wasn’t the only one to take its shot. The smallest of them all was the town of Phoenix, British Columbia (population about 1,000) who challenged for the Stanley Cup in 1911.

Phoenix is located in the south central part of the province, some 300 kilometres from Kamloops and just north of the border with Washington state. The area is known as the Boundary District. Copper was discovered near Phoenix in 1891, and by about 1895 a booming community grew up around the Granby mine. Hockey was introduced to the area a short time later.

The game caught on quickly, and received a big boost in the region in 1907 and 1908 when Frank and Lester Patrick moved to Nelson, B.C., with their father’s lumber business.

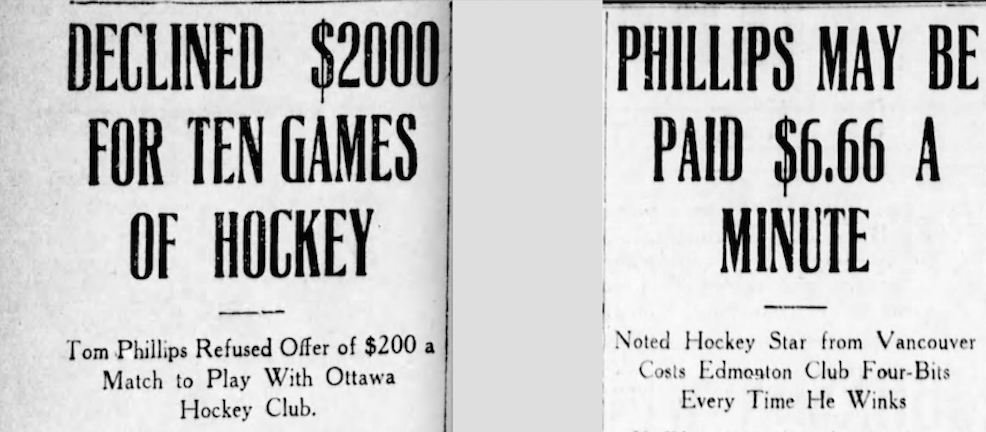

During the winter of 1911, the Boundary League featured teams in Phoenix, Grand Forks, and Greenwood. They played each other for times apiece, two at home and two on the road, giving the teams eight games over the six-week season. Phoenix had imported several new players from all across Canada this year, although none were names fans would recognize today. (You can read the names at the bottom the next clip.)

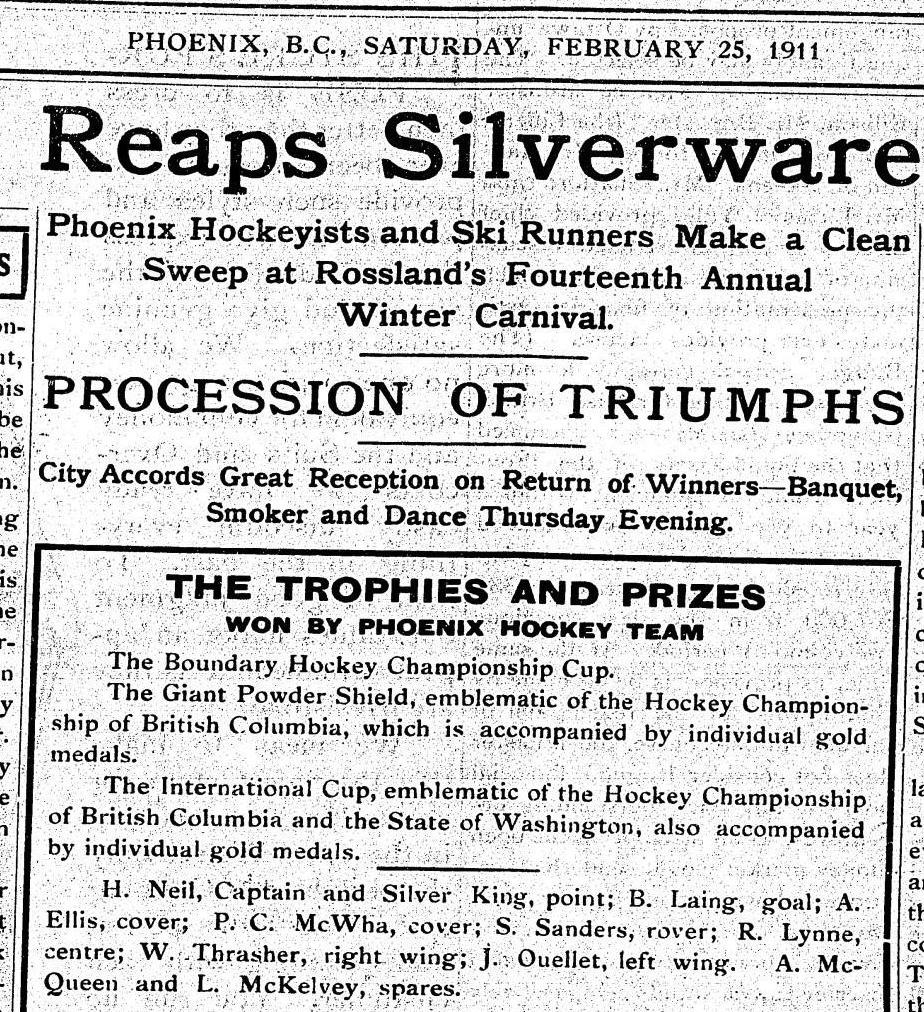

The season began on January 2 with Phoenix and Grand Forks playing to a 3-3 tie. Phoenix then rattled off five straight wins to clinch the title by January 30. Two more wins followed and Phoenix finished the season on February 13 with a record of 7-0-1. But in order to call themselves provincial champions and have a shot at the Stanley Cup, Phoenix needed to win the tournament at the annual Rossland Winter Carnival.

Phoenix claimed the British Columbia title by defeating a beefed-up team from Greenwood and then romping to an 8-2 win over hometown Rossland. They also won the Open challenge series, defeating Rossland once again and crushing the team from Missoula, Montana, 13-5. All four games were played in just five days.

Later, Phoenix beat Rossland one more time, pushing their record for the year to 12 wins and a tie in 13 games. Only one thing marred a nearly perfect season for Phoenix: they never got the chance to test themselves against the Patrick brothers and their powerhouse team in Nelson. Challenges were issued, but Nelson refused to play in the tiny rink in Phoenix, wouldn’t agree to meet the team on neutral ice, and didn’t offer any acceptable dates in their own rink. Nelson even took a pass on the Rossland Carnival.

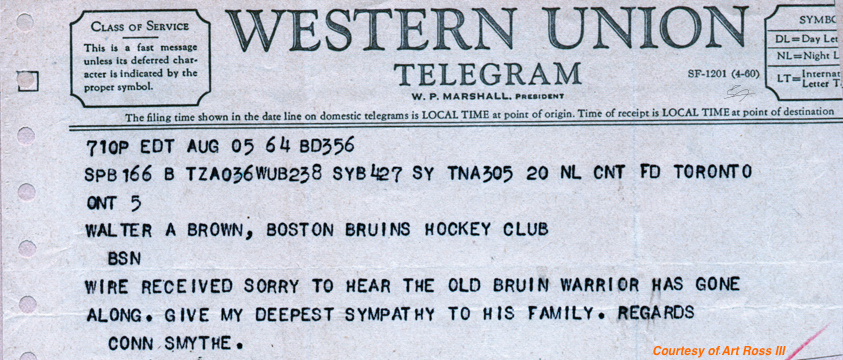

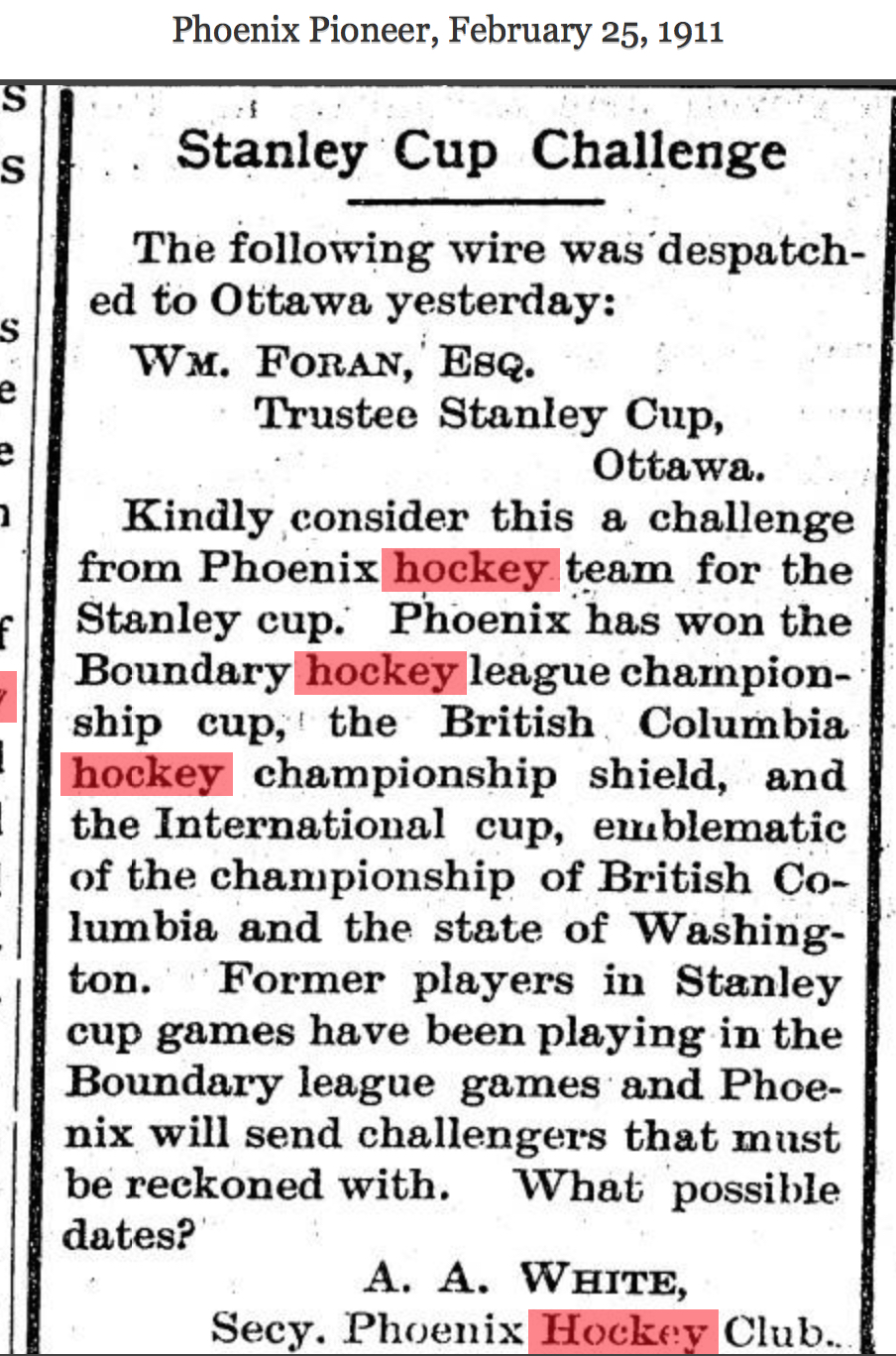

Undaunted, on February 24, 1911, a telegram was sent to William Foran, one of two trustees in charge of administering the Stanley Cup, asking for a series with the Ottawa Senators:

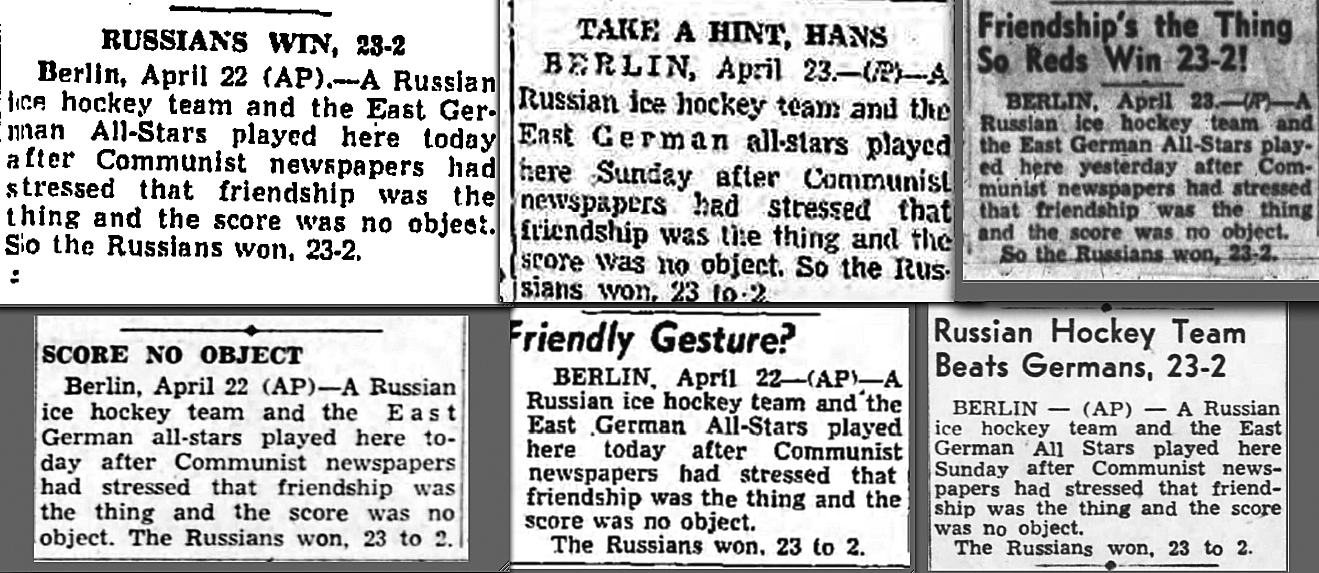

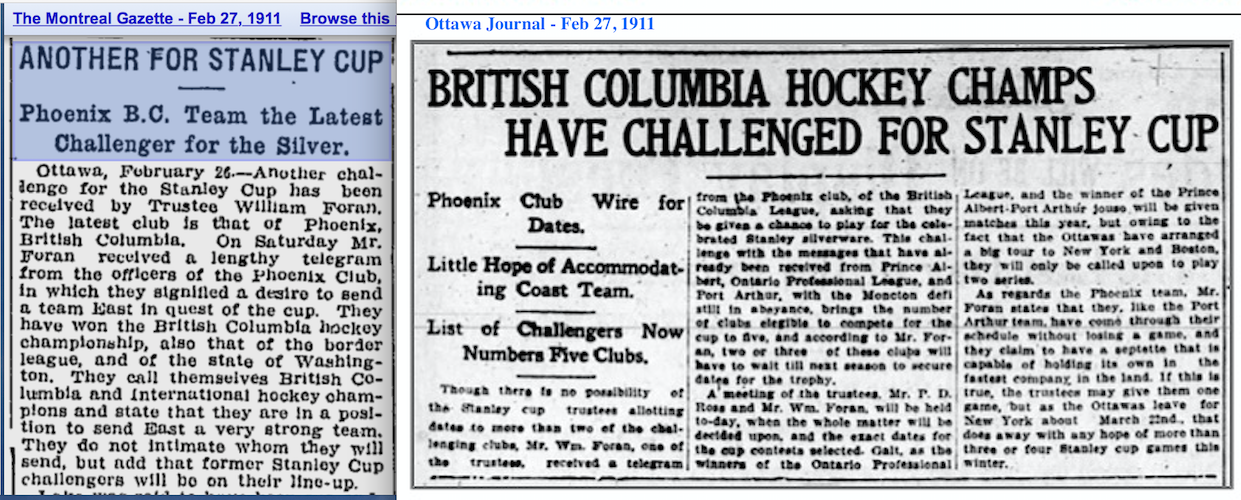

Newspapers across Canada reported on the Phoenix challenge, though few gave the team serious consideration.

When a reply came from William Foran, it was indeed bad news:

“Challenge received. Regret impossible to give you dates this season as there are three other challenges before the trustees. If you so desire will arrange for a series of matches with the holders of the cup at the opening of next season.”

It was strongly hinted that if Phoenix did get a chance to play for the Cup, they would add Frank and Lester Patrick to their lineup. However, as the 1911-12 season approached the brothers were busy creating the Pacific Coast Hockey Association. Phoenix never seems to have followed up with Foran.

The team continued to have success in the Boundary League in the years to come, but there would never again be a Stanley Cup challenge.

In the following years, many men from the tiny town of Phoenix found themselves fighting with the Canadian Army during the first World War. Fifteen sons of Phoenix gave their lives. In a sense, the town did too. The end of the War saw world markets for copper collapse, and in 1919 the Granby mine closed down. The town cleared out, with many former inhabitants leaving everything behind. By 1920, Phoenix was literally a ghost town.

Among the last projects planned in Phoenix was a monument to the local War dead. When many of the town’s buildings were sold for scrap, the $1,200 raised by the sale of iron and lumber from the local hockey rink was put toward the memorial. Today, the Phoenix Cenotaph is the only relic remaining from a once booming town that had hoped to win the Stanley Cup.

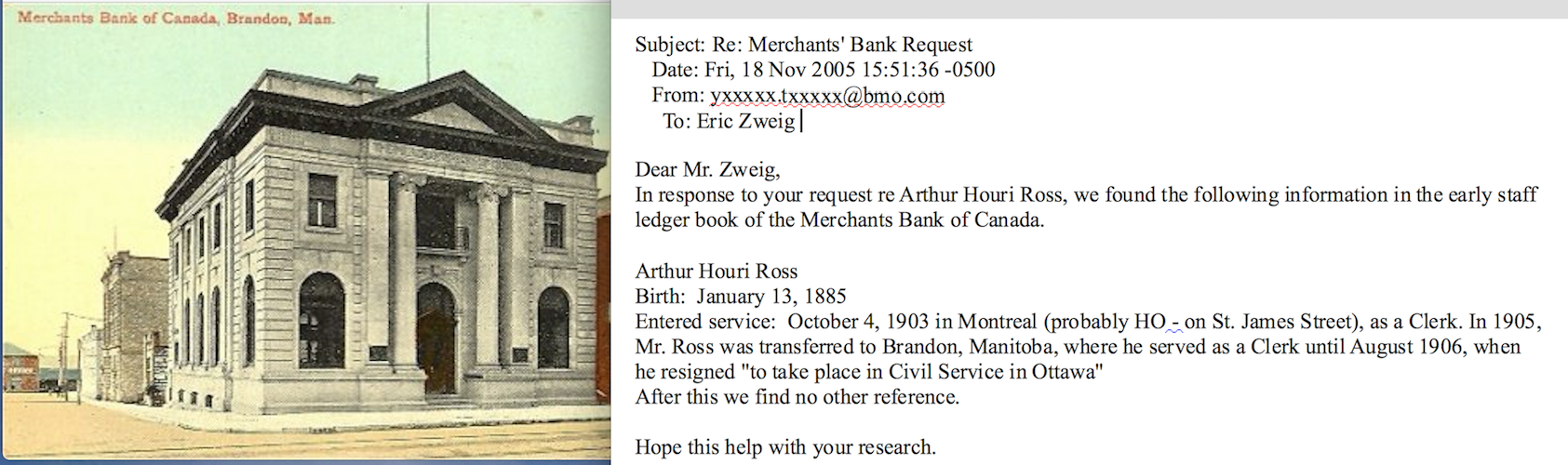

I was amazed that the Bank of Montreal HAS an archivist, and that she could find this …

I was amazed that the Bank of Montreal HAS an archivist, and that she could find this …