The NHL Official Guide & Record Book for the upcoming season was sent to the printer’s earlier this week. More on that in an upcoming post. For now, a story about my quirkiest contribution to this year’s Guide…

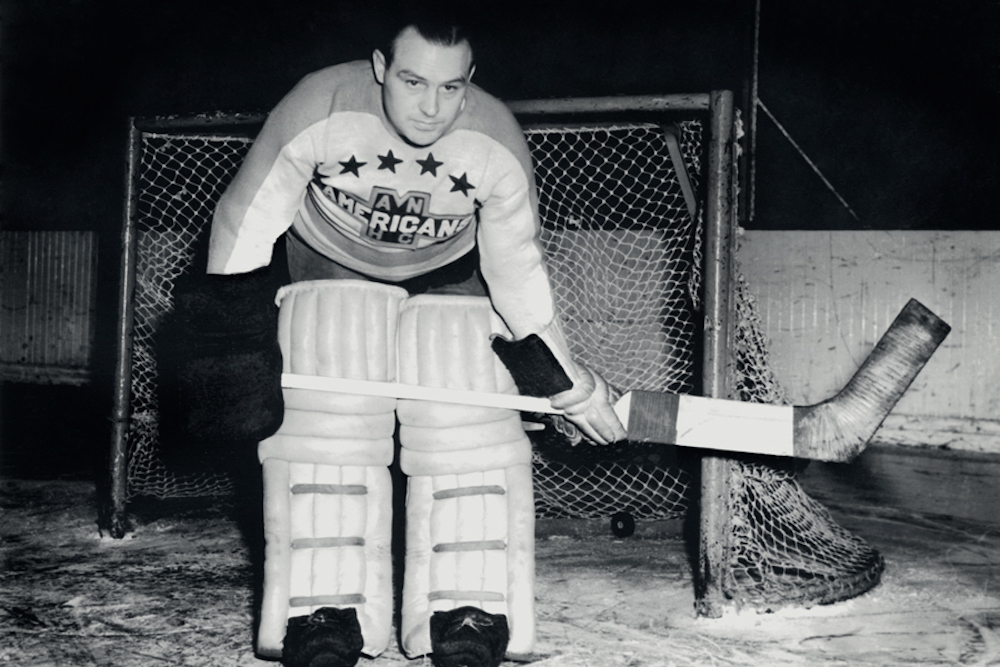

Godfrey Matheson is a name known only to hardcore fans of hockey obscurities. He was, very briefly, one of many coaches in the early history of the Chicago Blackhawks (then spelled Black Hawks). If you know the stories about him (and some of you will), you’re likely to know some variation of these:

- Matheson was from Winnipeg, home of Chicago’s star goaltender Charlie Gardiner.

- Matheson had little or no coaching experience when he was hired by Blackhawks owner Frederic McLaughlin after a chance meeting on a train.

- Matheson’s main claim to coaching fame was leading a Winnipeg high school team to a juvenile championship.

- Matheson devised a system of coaching the Blackhawks by whistle, which he would use to signal his players from behind the bench. One blast instructed the puck-carrier to pass; two toots meant shoot; three signalled a switch in defensive formation.

Strange as it sounds, most of these stories appear to be be true … except that Matheson never actually coached a regular-season game in his NHL career!

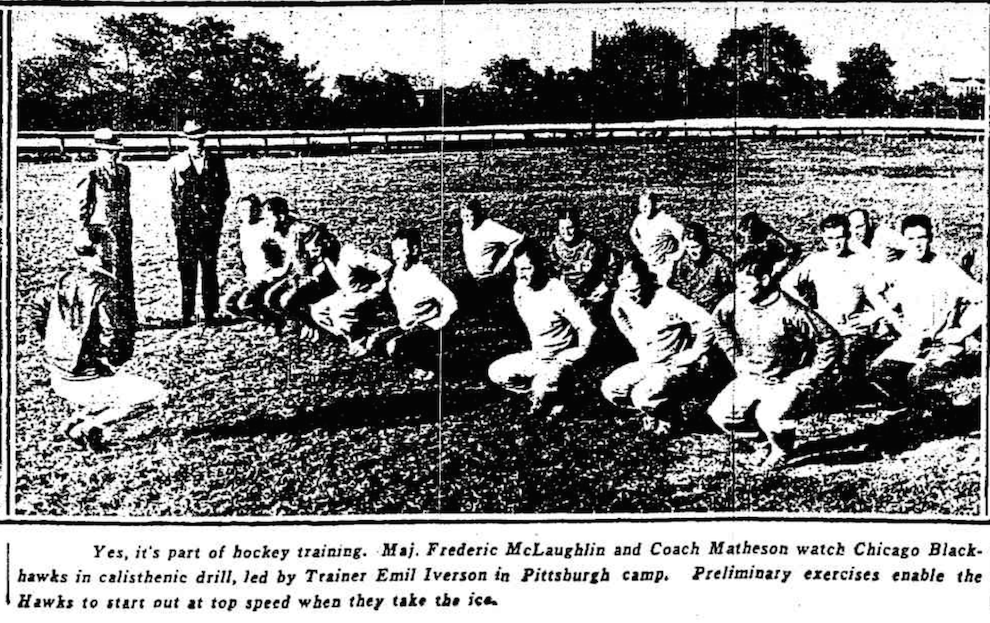

This picture appeared in the Chicago Tribune on October 15, 1931 with the story announcing the hiring of Godfrey Matheson. He appears at the far left, with the hat low over his eyes.

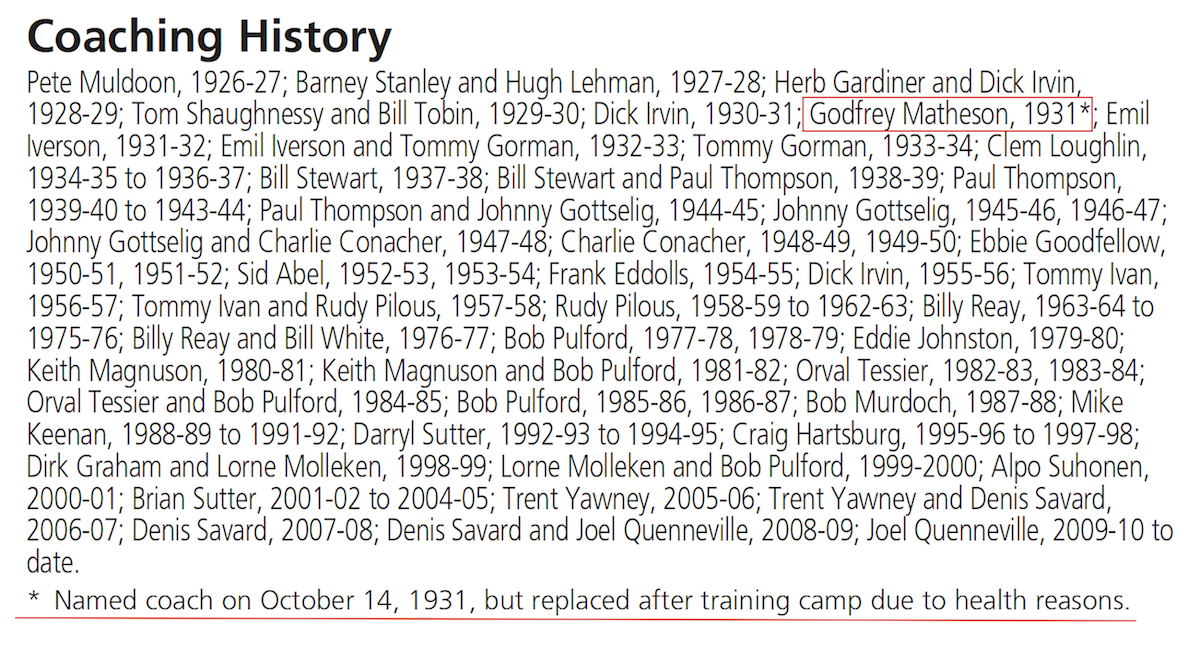

For decades, NHL records have shown Godfrey Matheson coaching the Blackhawks midway through the 1932-33 season. He was thought to have held down the job for just two games between the brief tenures of Emil Iverson and Tommy Gorman. In fact, Matheson was actually hired in October of 1931, but by the time the season started on November 12, 1931 – with Chicago visiting Toronto for the opening of the brand new Maple Leaf Gardens – he was no longer with the team.

Frederic McLaughlin had a penchant for firing his hockey coaches in a way that makes the late George Steinbrenner’s treatment of his baseball managers seem almost tame by comparison. McLaughlin was married to Irene Castle, a jazz-era dance, film and fashion icon who was played by Ginger Rogers opposite Fred Astaire in the 1939 film The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle. Irene wrote a serialized newspaper biography that appeared in the Chicago Tribune late in 1958. She paints a rather unflattering picture of McLaughlin.

“The early 1930s were not good years for me,” writes Castle, “but not for the same reason they were bad for the country. My trouble was not money. Instead, it was the slow decline of a marriage which had not been too satisfactory even in its early stages. Frederic became interested in a hockey team, which kept him in a temper much of the time.”

Castle describes McLaughlin as running his team “with the zeal of an amateur who doesn’t know what it’s all about.”

“I often wished he had never seen a hockey stick,” she says. “He was always getting mad at somebody.… His favorite sport was quarrelling with [coaches].”

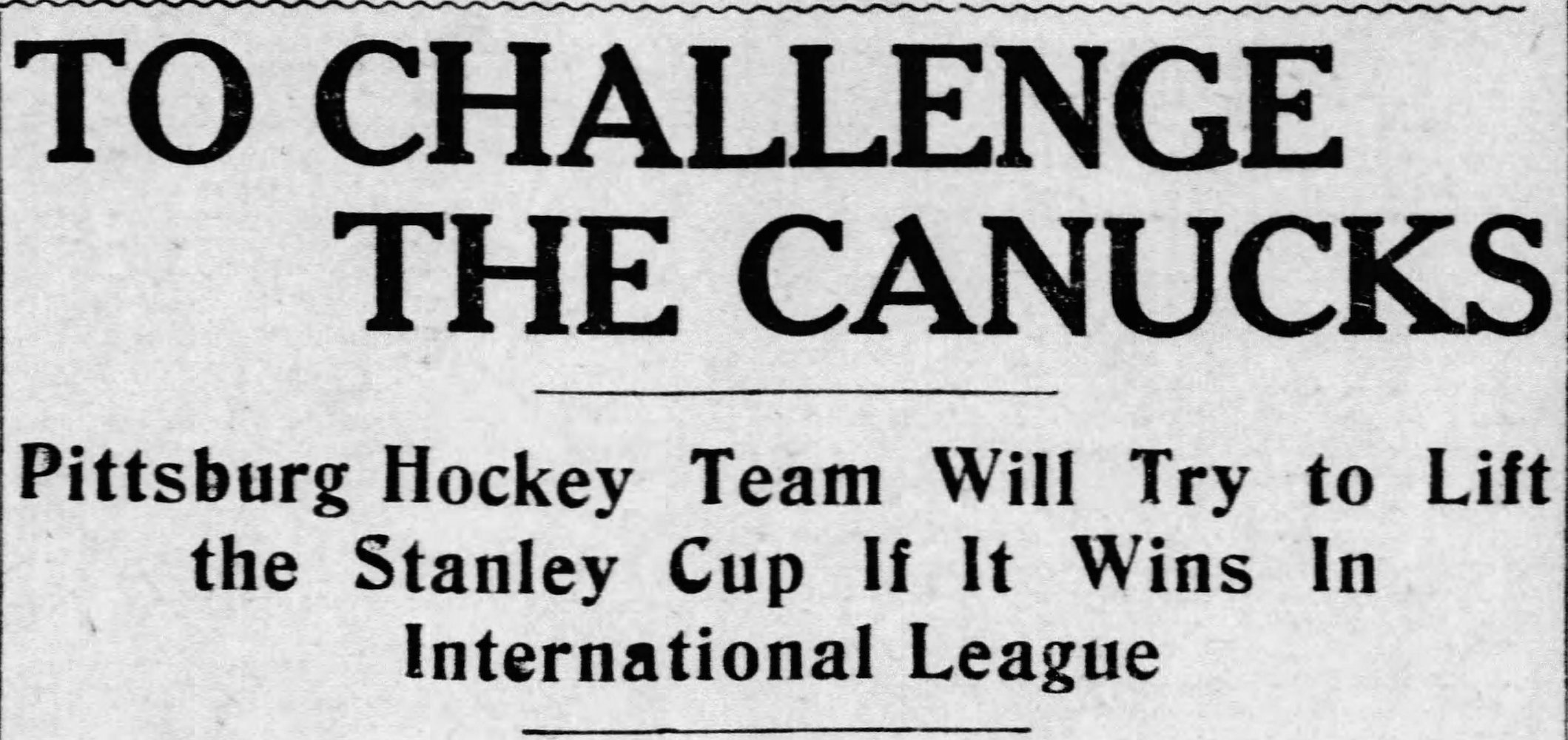

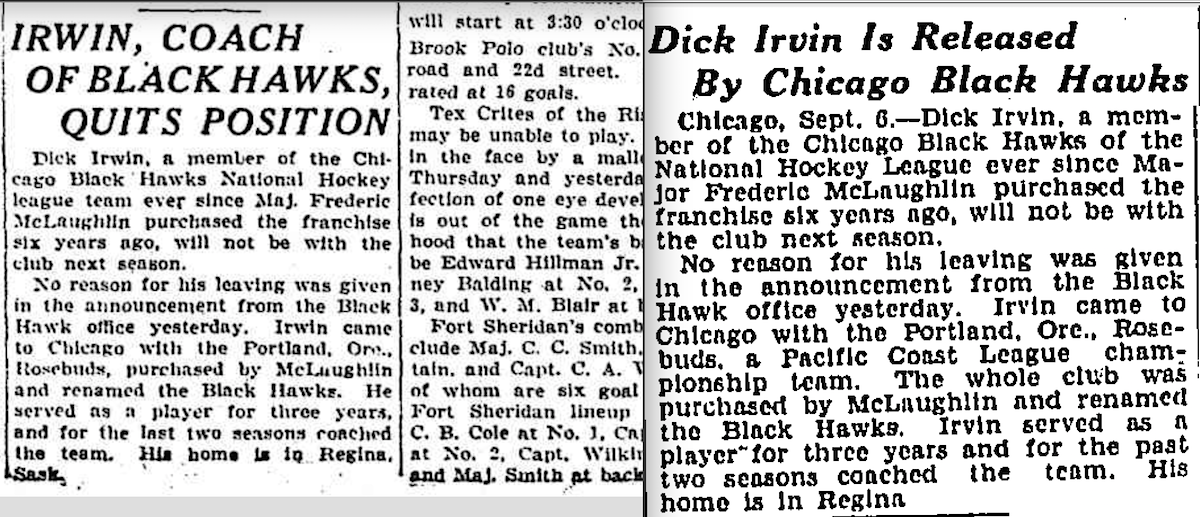

Stories from the Chicago Tribune on September 6, 1931,

and the Globe in Toronto on September 7.

Dick Irvin, for example, had been the first star player in Chicago, and coached the team after a fractured skull ended his playing career. Irvin coached Chicago to the Stanley Cup Final in the spring of 1931, but that wasn’t enough to keep him employed and he became the seventh coach to lose his job in the five-year history of the team.

Some records show Irvin beginning the 1931-32 season as the coach in Chicago before moving on to join the Maple Leafs in Toronto five games into the schedule. The truth is he was fired or quit on September 5, 1931, six weeks before the Blackhawks began training camp. Irvin offered little about the reason for his departure in newspapers over the next couple of days, but it was later reported by Globe sports editor Michael J. Rodden that Irvin had not been in agreement with training methods favoured by Chicago management. Enter Godfrey Matheson, who was hired by the Blackhawks on October 14, 1931.

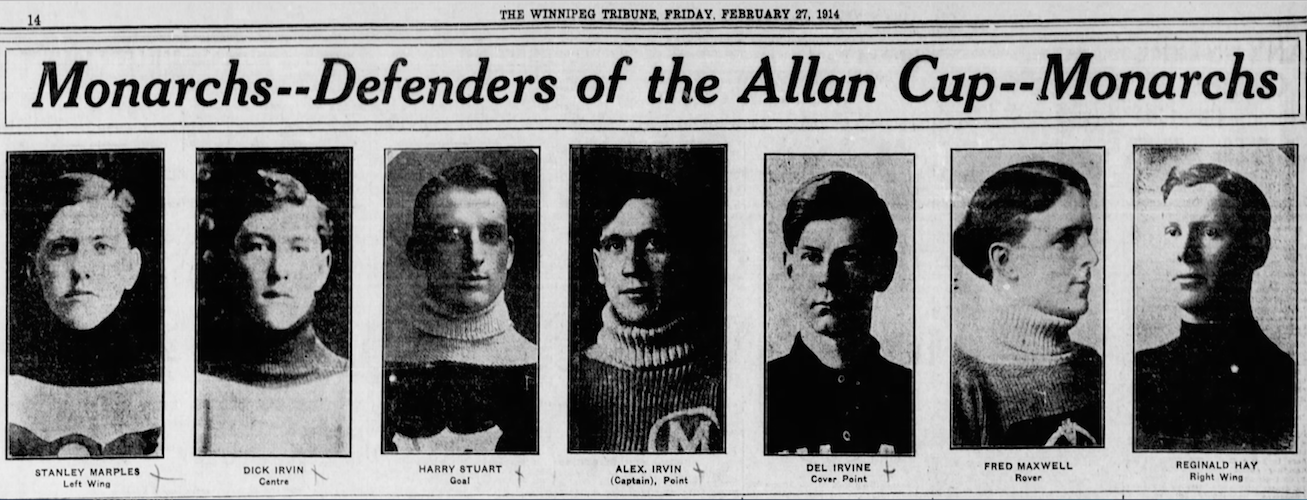

Stories at the time make no direct mention of McLaughlin and Matheson meeting on a train, but do state his brief success as a coach at St. John’s College in Winnipeg. Stories in the Winnipeg Tribune on October 24 and 28 discuss his having played earlier at the same school, and later with the Winnipeg Victorias team in the Winnipeg city league and with a local Bank of Commerce hockey team.

This photo appeared in the Chicago Tribune on October 23, 1931.

The Blackhawks and their new coach left Chicago for training camp in Pittsburgh on the evening of October 14. They would work out on the ice at Duquesne Garden, in the gymnasium at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, and engage in outdoor runs when the weather permitted. It would be years before stories of Matheson’s whistle system appeared in newspapers, along with tales of him training his goaltenders by have as many as three or four pucks at a time thrown at them (not shot) from all angles. Even so, Toronto Star sports editor Lou Marsh, writing on the eve of the new season on November 11, 1931, hinted at the unusual tactics and described Matheson’s odd attire at training camp: “He wore skates and knee pads – and had his garters on the outside of his knee pants… He looked like he was going to lay a cement sidewalk.”

But by then, Matheson was no longer with the Blackhawks. The Chicago Tribune reported on November 10, 1931, that the coach had entered a Pittsburgh hospital the day before with a stomach ailment. The Toronto Telegram had a very different story when the Blackhawks arrived to face the Maple Leafs without their coach: “Godfrey Matheson … has departed to Florida, a victim of a nervous breakdown.”

The Telegram believed that Matheson may have jumped the team before he was pushed, but a story in the Winnipeg Free Press on December 3, 1931, would note that Matheson was spending the winter in Daytona Beach after being ordered by doctors “to take a long rest.” His health was reported as improving, “but he will be unable to rejoin the team this season.”

And he never did. So, in consultation with the Blackhawks (they had a few other things wrong; so did we) and the NHL’s long-time statistician Benny Ercolani, here is the new Chicago Coaching History that will appear in the NHL Guide beginning this season:

There are also a few corresponding changes to coach’s Win-Loss records in the early years.

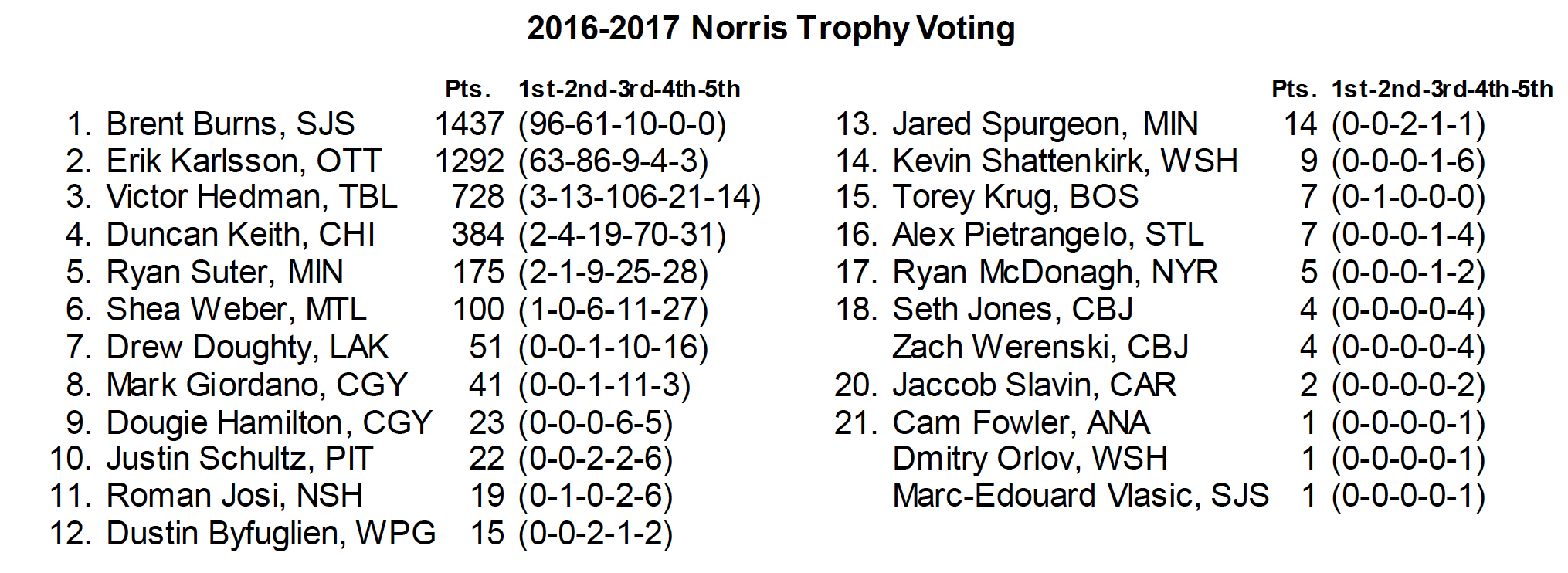

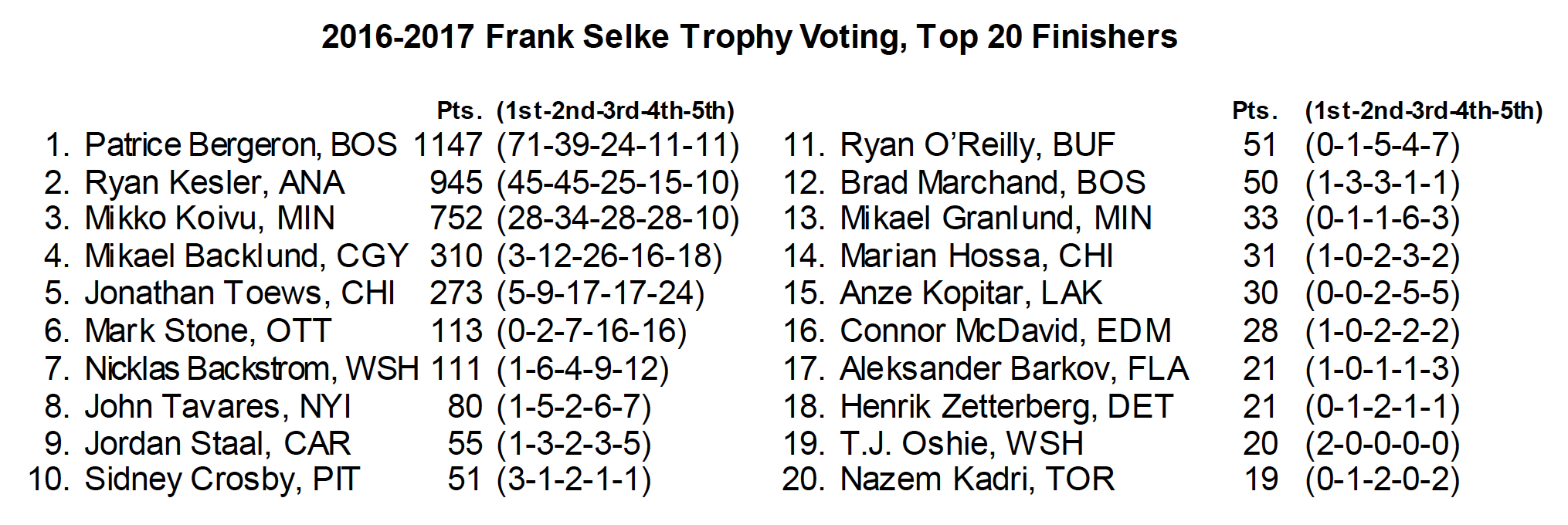

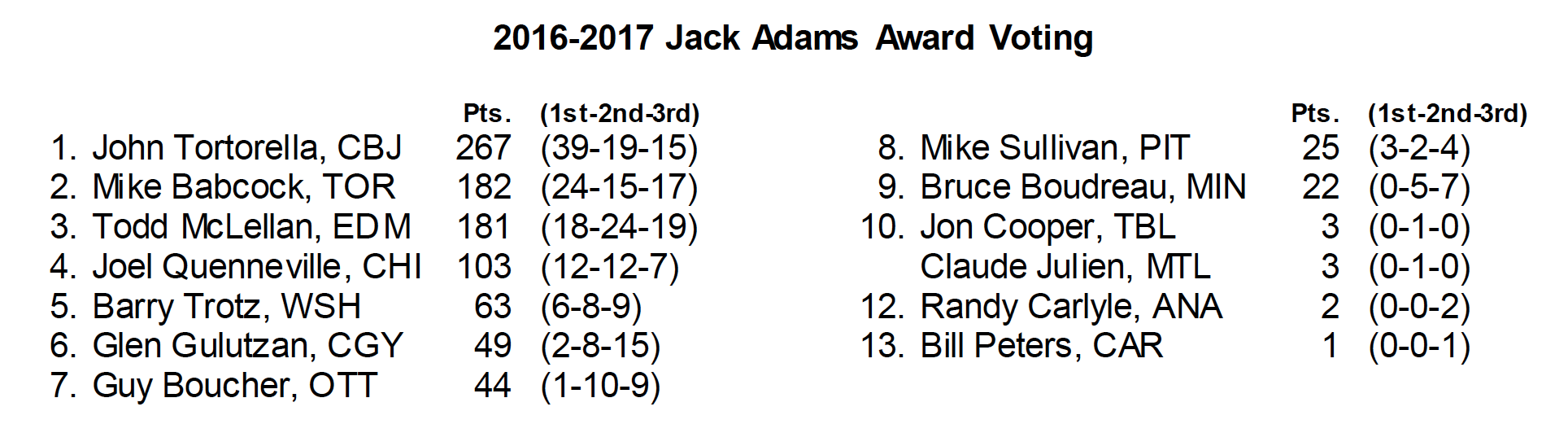

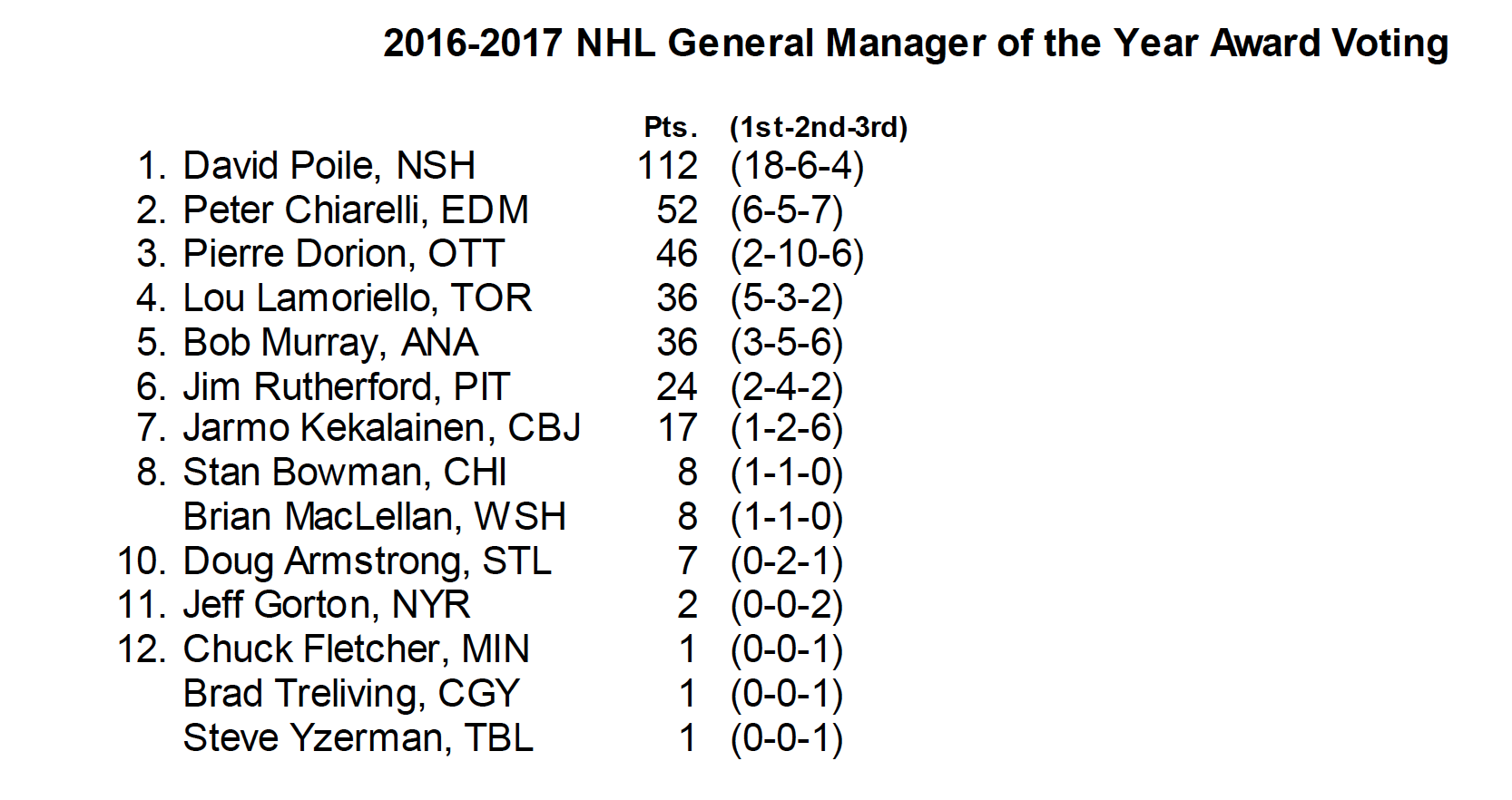

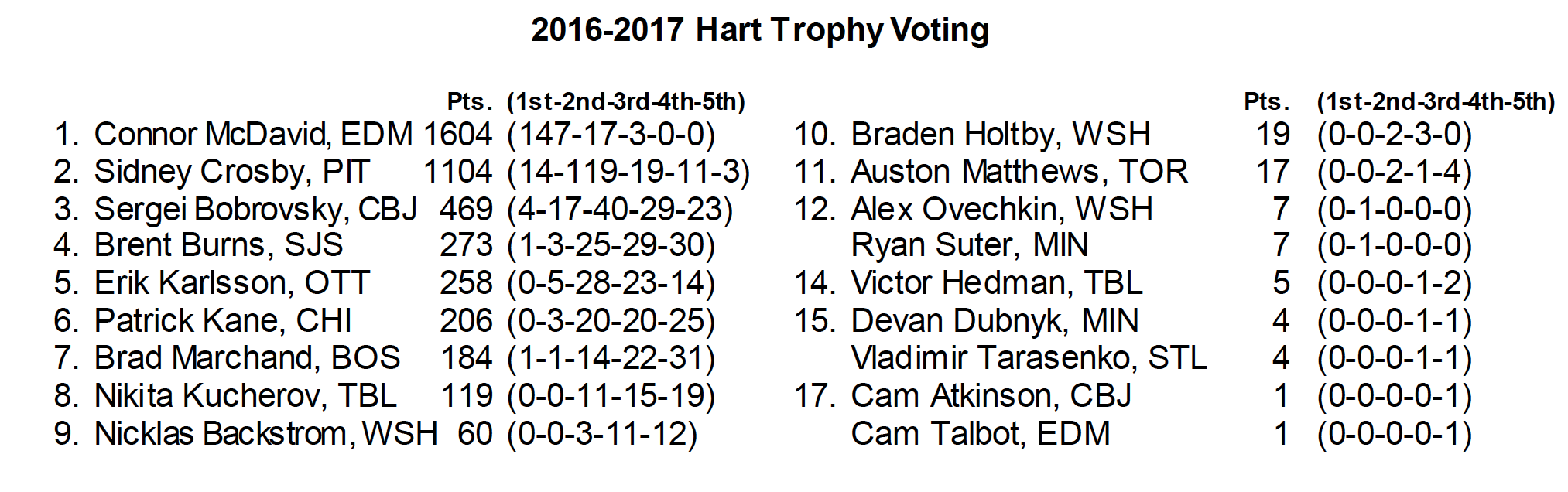

Selected from 167 votes cast by the Professional Hockey Writers Association.

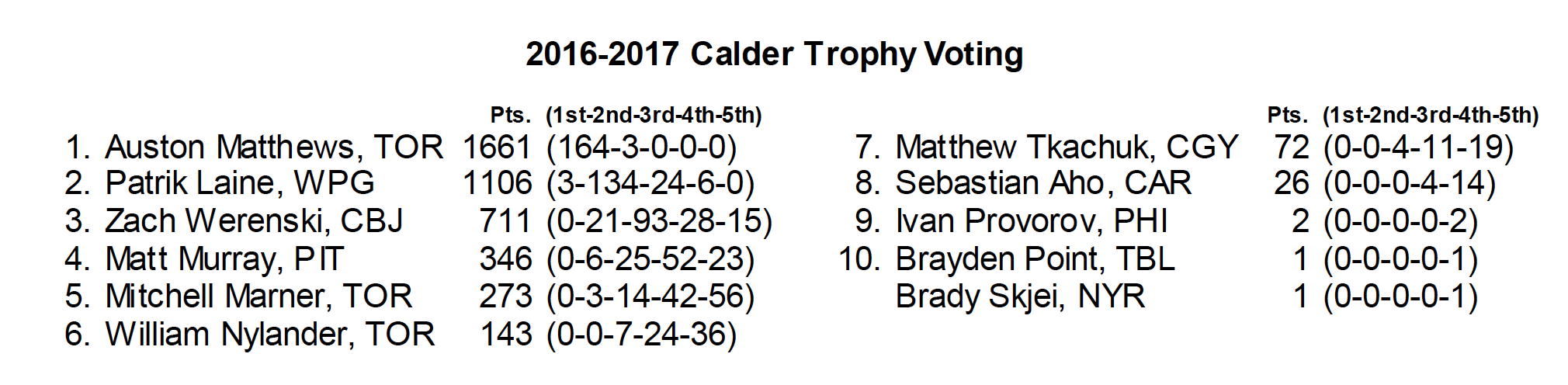

Selected from 167 votes cast by the Professional Hockey Writers Association.