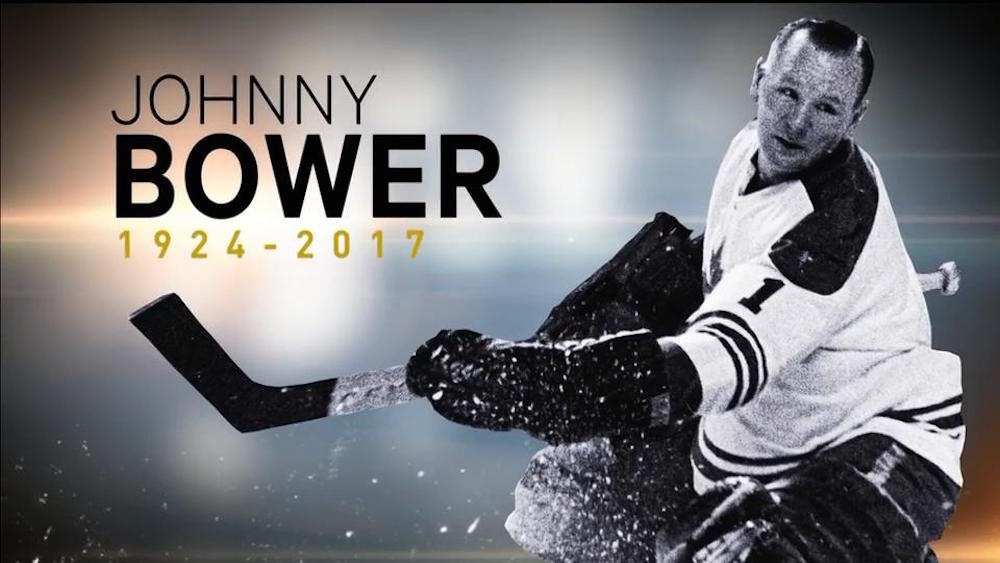

I’ve been writing (and talking) about Johnny Bower a lot about lately. I wasn’t planning to do it again this week, but I’ve been pretty interested (some might say obsessed!) with certain aspects of Bower’s early hockey career and how it’s tied up with his unusual military career. So this story is something of a sequel to my piece Before He Was Bower, which I posted on December 28.

In his 2006 autobiography The China Wall, which Johnny Bower wrote with longtime hockey writer Bob Duff, Bower says that when he was playing hockey as a boy in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, there was an army reserve unit in town. “A lot of us kids from the hockey team used to go every Friday night. We had uniforms and they trained us. It was good fun.” Bower says that, “when the war broke out, I was 15 and most of the guys joined up.”

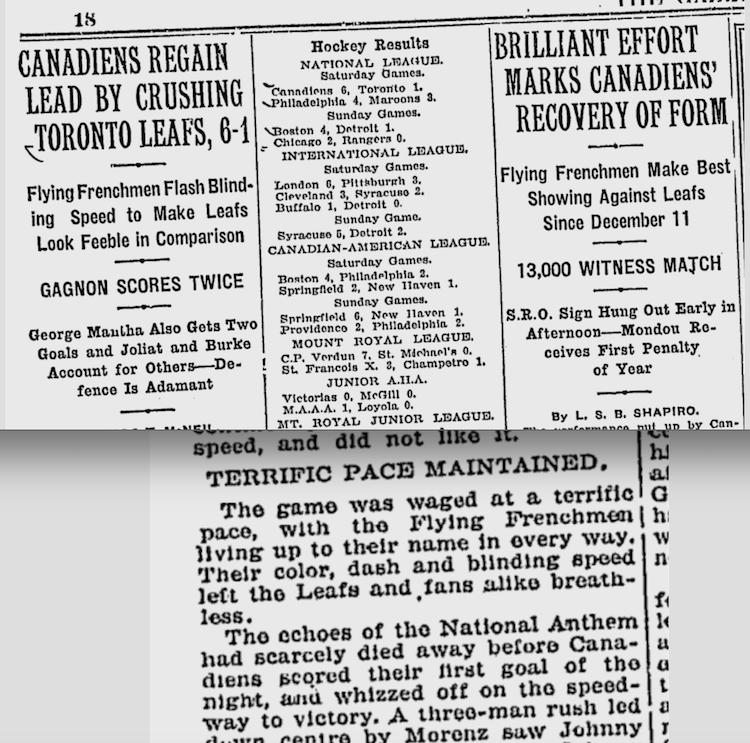

Johnny Bower was still Johnnie Kiszkan when he played wartime hockey in Vernon,

British Columbia. The newspaper clipping is from the Regina Leader-Post on

March 4, 1943. The playoff recap is from Ice Hockey Wiki.

With a birth date of November 8, 1924 (when he was born John Kiszkan), Bower would still have been 14 when World War II began in September of 1939. Perhaps he waited a few months to enlist. Most of his Prince Albert buddies were sent to Vernon, British Columbia for training – but Bower was held back for a few months “because one of the generals found out how young I was.”

Bower was eventually sent to British Columbia for further training, but “they found out when I was in Vernon that I was too young, so I was stationed there for two years.” He may actually have been there for closer to three years.

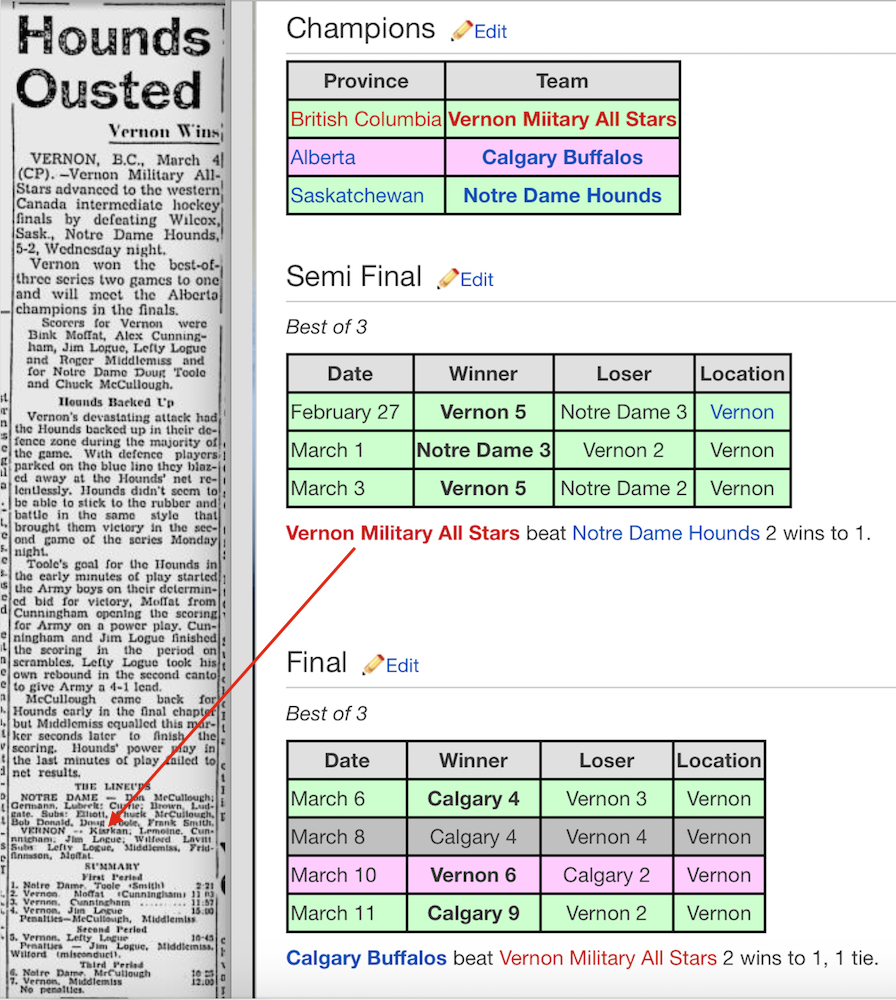

Tom Hawthorn, a veteran reporter who lives in Victoria, B.C., recently had a great story about Johnny Bower in an online British Columbia news magazine called The Tyee. It includes an account of Kiszkan/Bower playing goal for the Vernon Military All-Stars during the winter of 1942-43. Hawthorn relates that Bower led his team to the British Columbia intermediate provincial championship, followed by victory over the Saskatchewan champion Notre Dame Hounds before losing the Western Canadian title to the Calgary Buffaloes in mid-March of 1943.

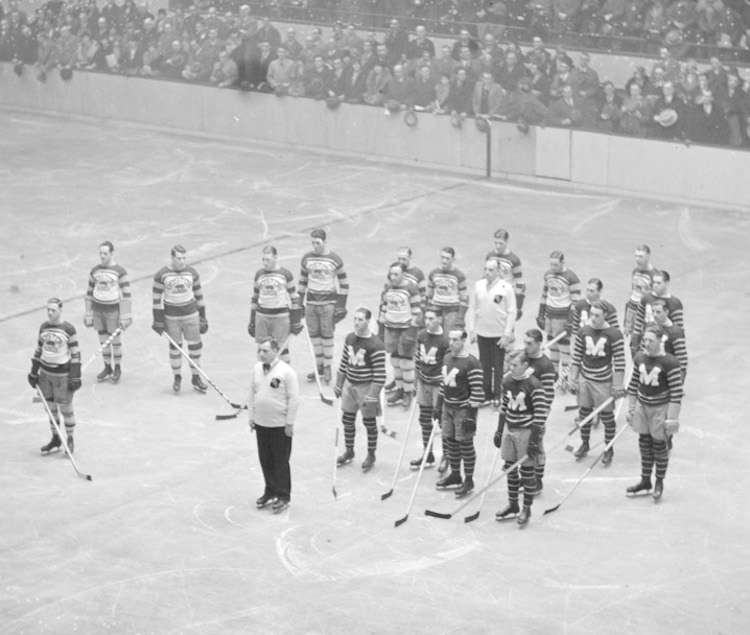

Johnny Kiszkan/Bower sits in the middle of this team photo of the Prince Albert M&C Warhawks, between two of the three trophies he helped the team win in 1943-44.

Sixty years later, in a 2003 interview (much of which appeared recently as a lengthy obituary in The Globe and Mail) Bower told Regina sportswriter and historian John Chaput that, “I went overseas around 1943 and I was going to play hockey at one of the camps, but when I arrived I found that Turk Broda and pretty well all the pros that played for the Maple Leafs were on this hockey team, so I turned around.”

This appears to make it impossible for Bower to have had the near-miss at Dieppe due to illness in 1942 that I wrote about in December, and which he himself discussed in The China Wall. Still, much of Bower’s overseas experience in 1943 was spent in hospitals as he battled rheumatoid arthritis. By January of 1944, he was back in Saskatchewan and would soon be out of the army. Bower returned to Regina, got a discharge, and went to Saskatoon. He writes that he then went back to Prince Albert, “and got a job on the railroad.”

At this point, virtually all hockey sources – and Bower himself – have him returning to the game as a Junior with the Prince Albert Black Hawks for the 1944-45 season. But as I more-or-less stumbled across in my December story, Bower/Kiszkan had returned to the ice almost as soon as he got home. I contacted John Chaput about this and he agreed to go through the Prince Albert Daily Herald on microfilm at the Provincial Archives in Regina for the winter of 1943-44. Here’s what we’ve found.

A closer look at a young Johnny Kiszkan/Bower from the M&C team photo.

There was a four-team Prince Albert City League in 1943-44. They played a six-team double-round robin schedule. Bower/Kiszkan wasn’t a part of the league, but did play on a Prince Albert All-Star team in an exhibition game against the Saskatchewan RCAF Tech Aeronauts on January 22, 1944. In hyping the game on January 19, the Prince Albert newspaper noted: “An added attraction will be Pte. Johnnie Kiszkan, late of the Prince Albert Black Hawks and Victoria [likely Vernon] Army, who will be netminder for the All-Stars. Johnnie recently returned home from action overseas.” Perhaps he’d already been playing hockey in Regina or Saskatoon, as Johnnie and the All-Stars won the game 6-3.

The Prince Albert M & C Repair Depot team — sponsored by the M & C Aviation Company and known as the Warhawks — finished in first place in the City League standings. Kiszkan/Bower didn’t play for any team that season, but the Warhawks were also the only Intermediate hockey team in Northern Saskatchewan, and they added Johnnie Kiszkan to their roster for the playoffs against the Southern champions:

Feb. 25/44: Notre Dame Hounds 2 at M&C 5

Feb 27/44: M&C 4 at Notre Dame 0

(M&C wins total-goal series 9-2 and wins Henderson Cup as Saskatchewan intermediate champions.)

He remained with the team to face the Alberta Champions too:

March 17: Canmore Briquetters 2 at M&C 3

March 18: Canmore 1 at M&C 4

(M&C wins best-of-three series 2-0 and Edmonton Journal Cup as Western intermediate champs.)

Kiszkan/Bower played two more games that year, on March 30 and April 1 when the M&C Aviation Warhawks defeated Prince Albert Army 5-2 and 2-0 to win the Quinn Cup as Prince Albert City champions.

A closeup look at the team plaque on the Henderson Cup from 1943-44. (Thank

you to Brock Gerrard, Curator of the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame in Regina.)

“It’s only a few games, and against diluted wartime competition,” says John Chaput, “but the goals-against average is pretty gaudy; 1.43 overall, 1.17 if you exclude the exhibition, 1.25 for the four games that really matter…. There are no quotes in any of the stories and the game descriptions are rather general, but the one thing about Kiszkan/Bower that is evident is [his style]. Against Notre Dame, “Kiszkan displayed some remarkable footwork in warding off the attacks of the determined Hounds.” Against Canmore: “Much credit for the win goes to Kiszkan for kicking out a good many ‘labelled’ shots.”

The poke check would come later!

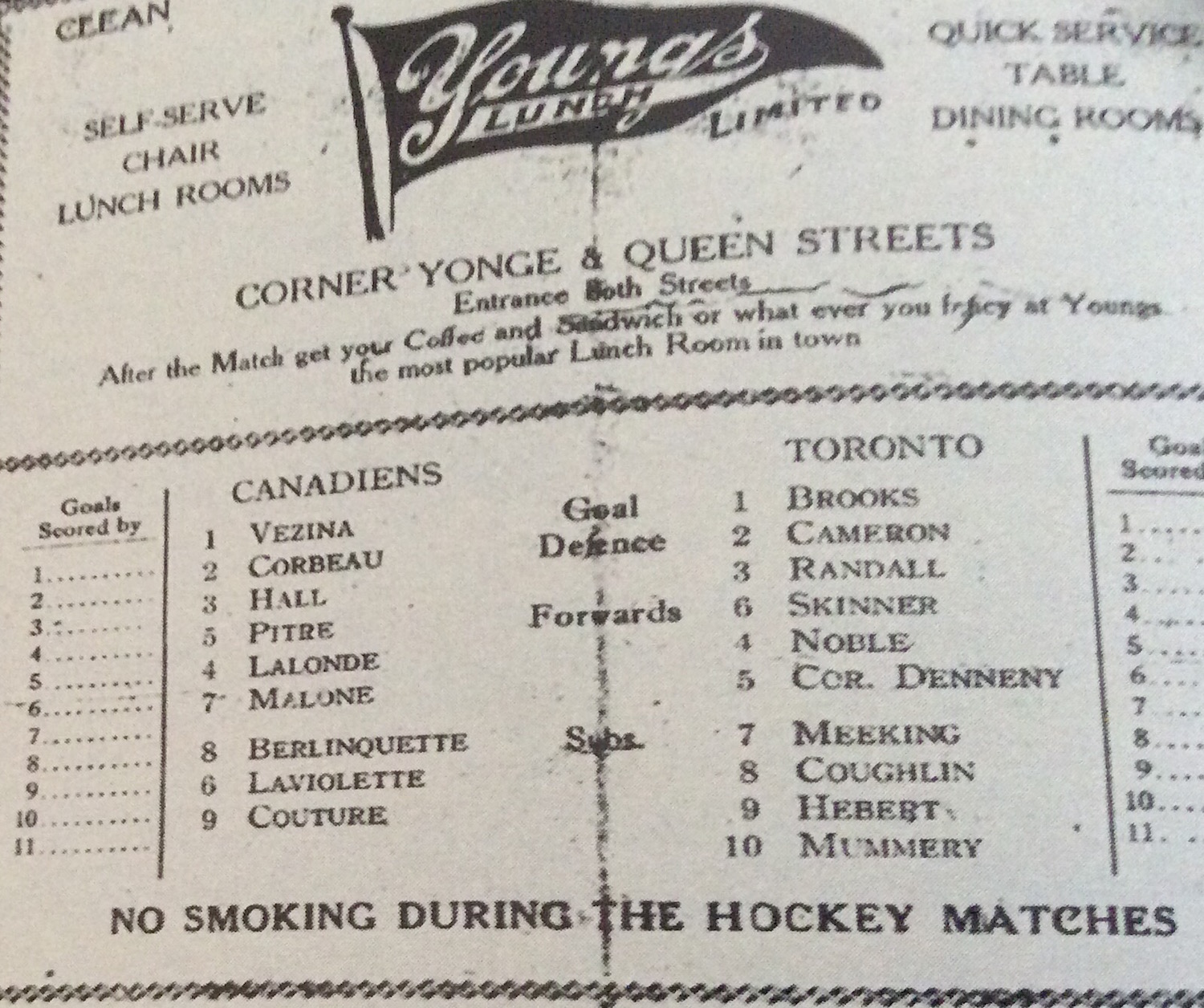

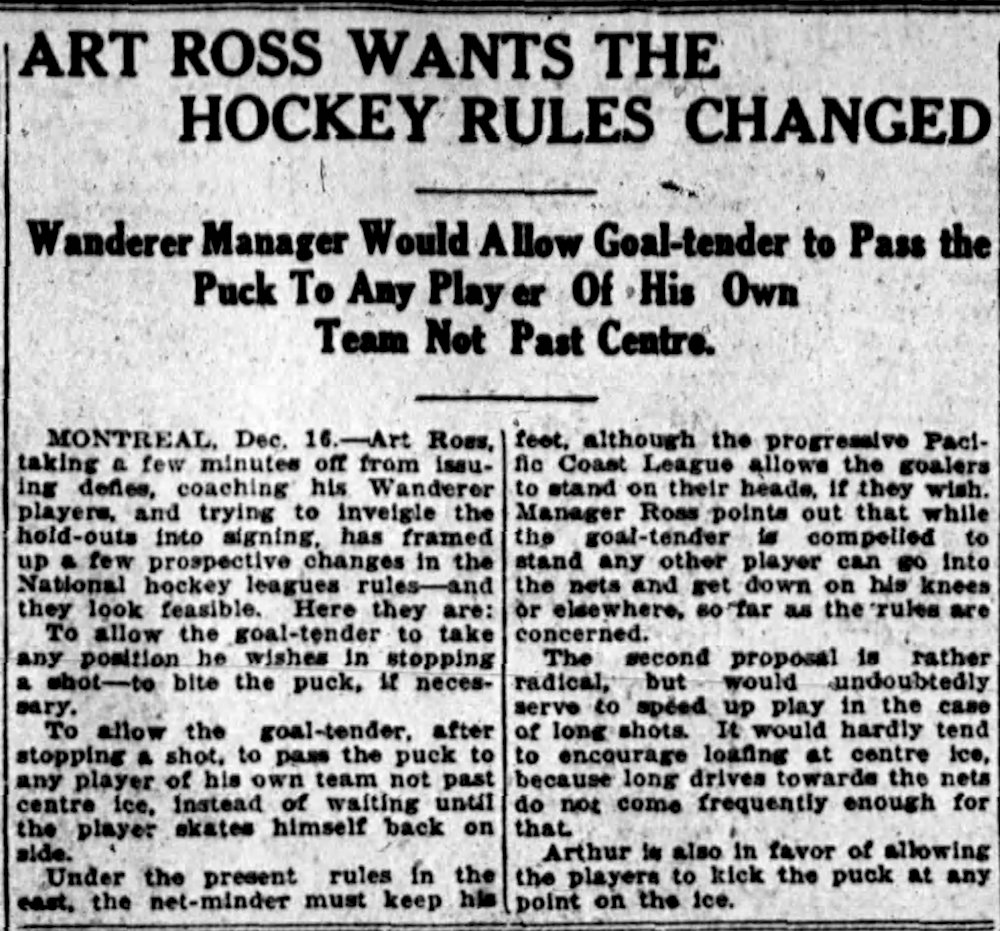

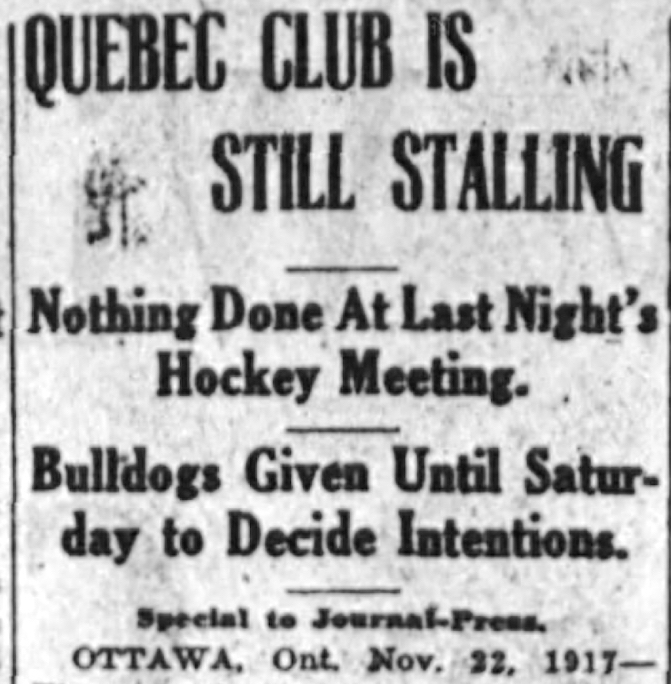

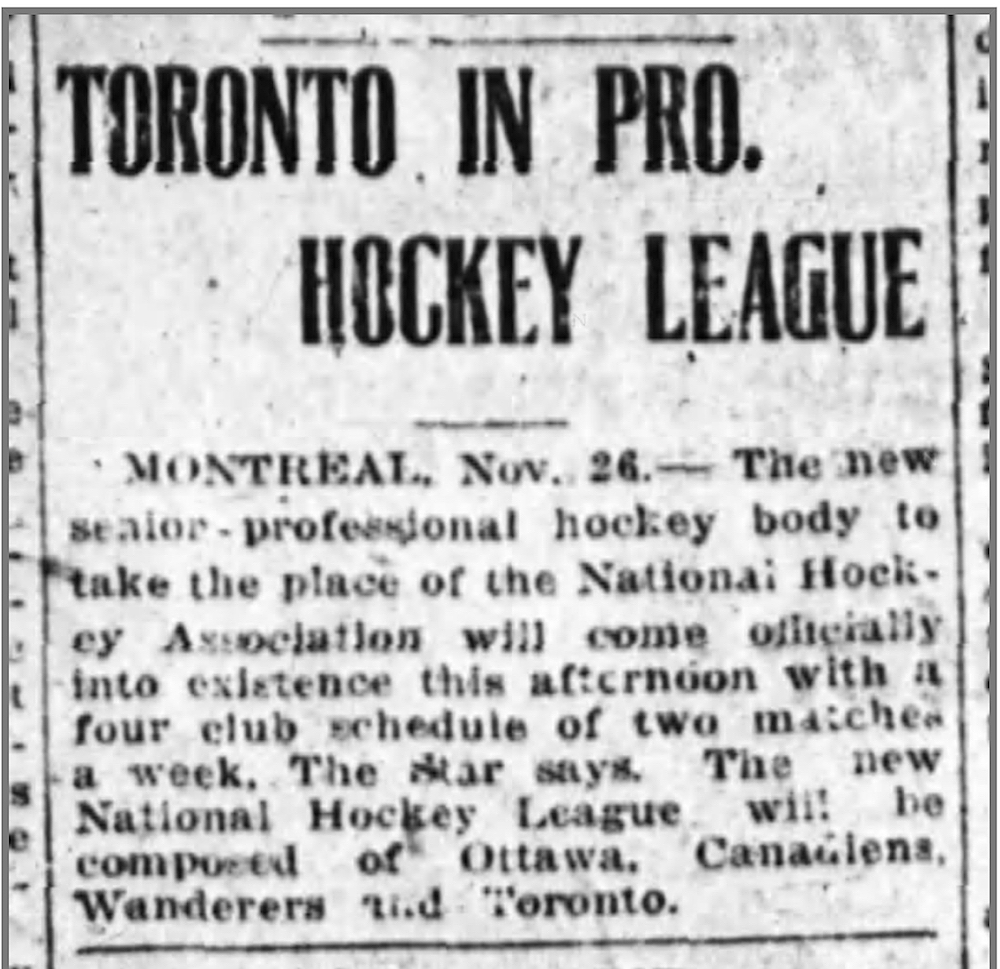

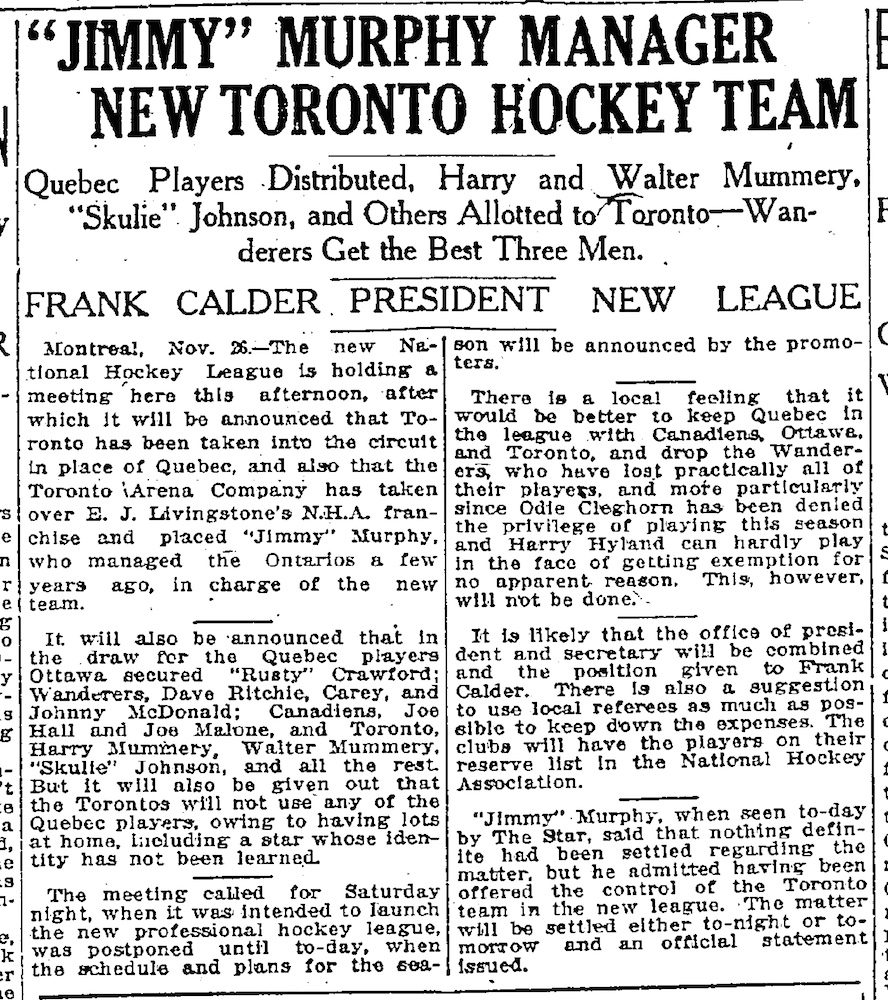

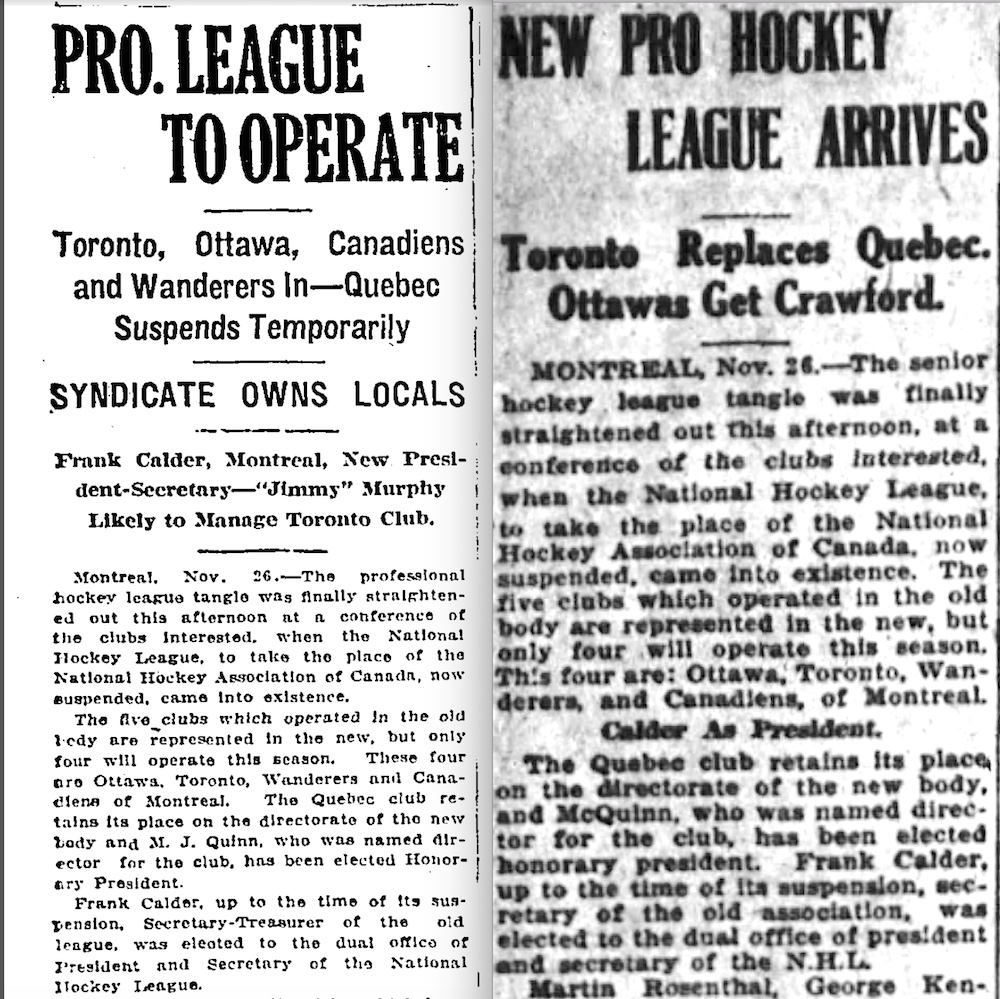

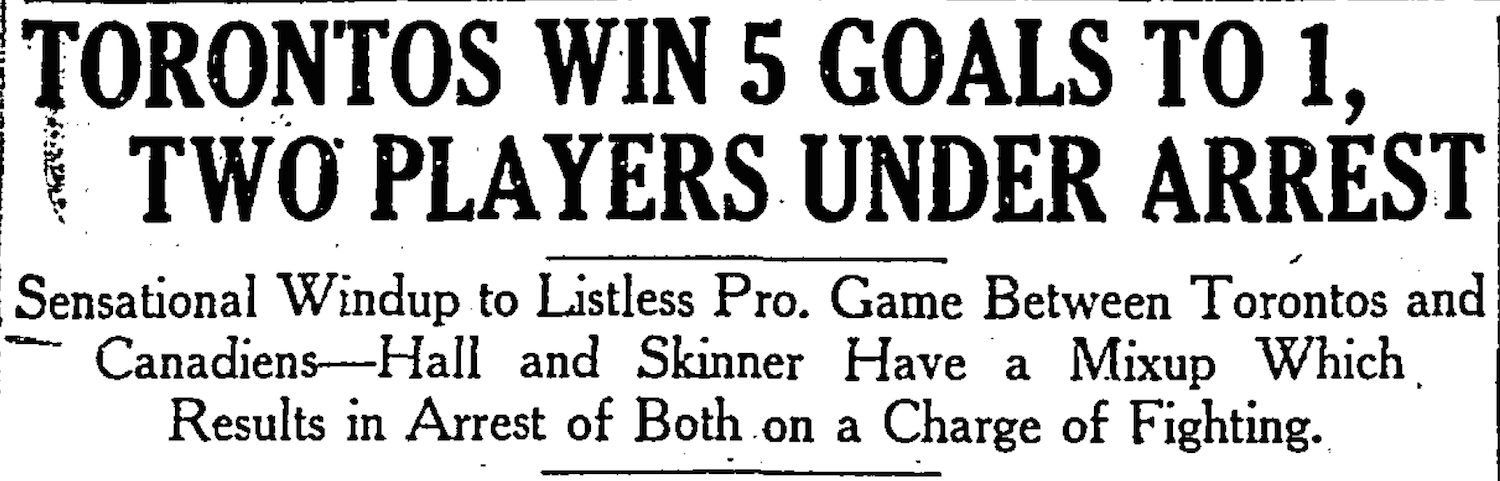

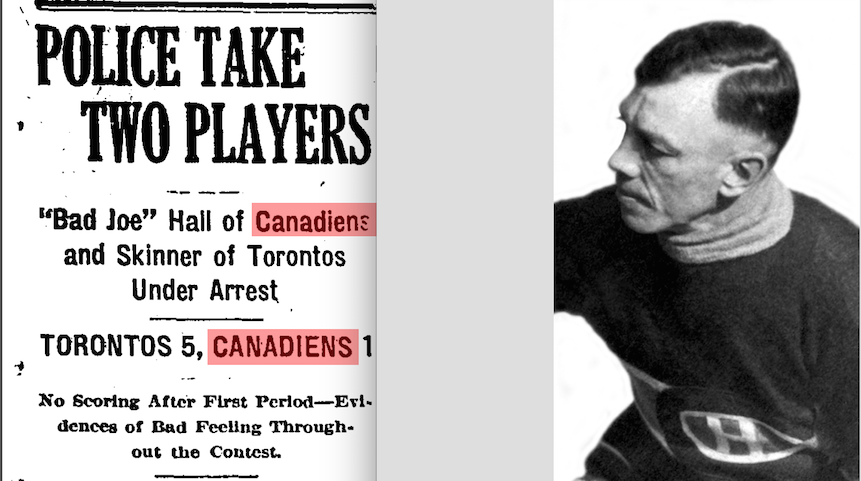

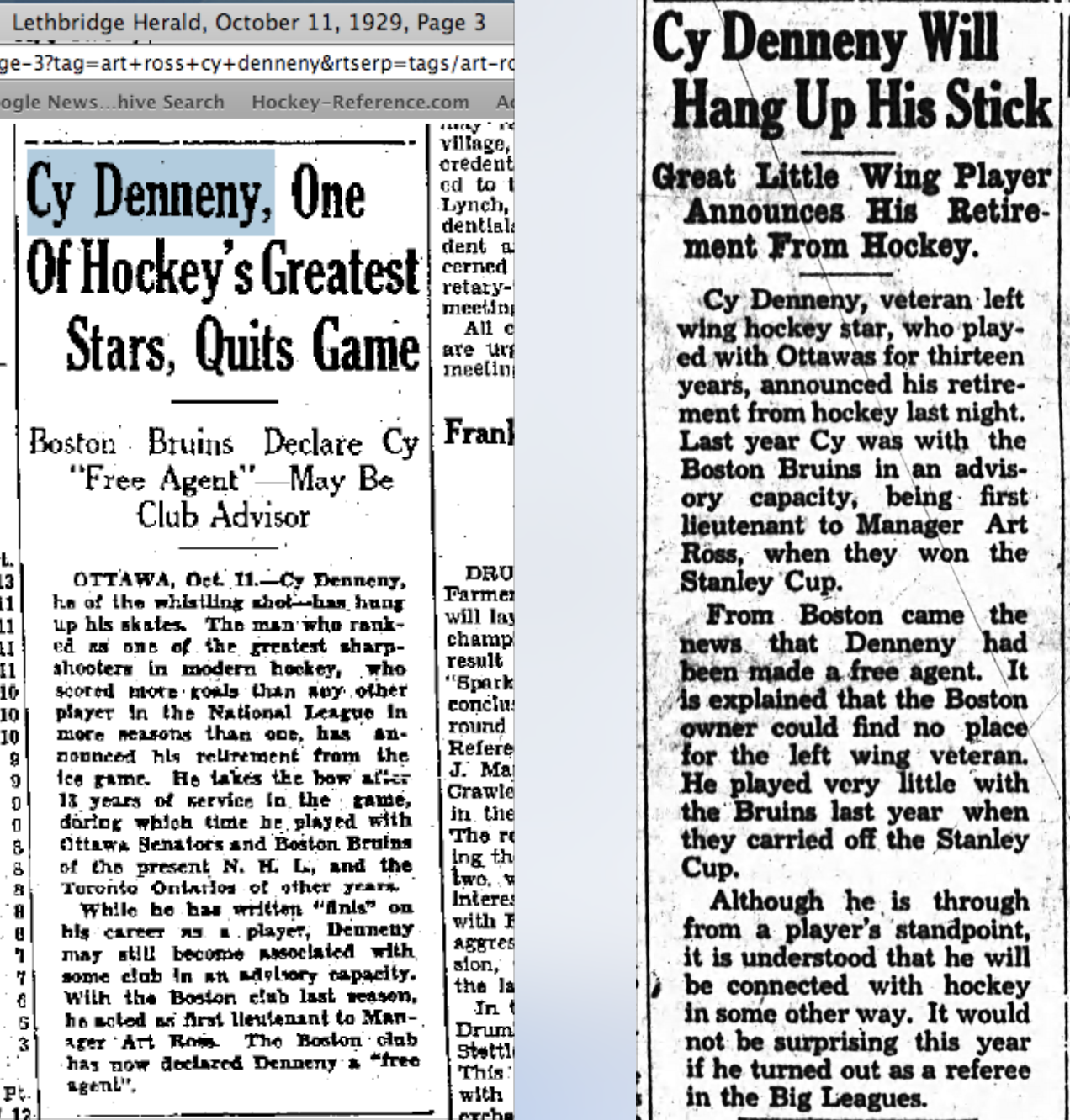

Ad for Toronto’s NHL opener in The Globe on December 22, 1917.

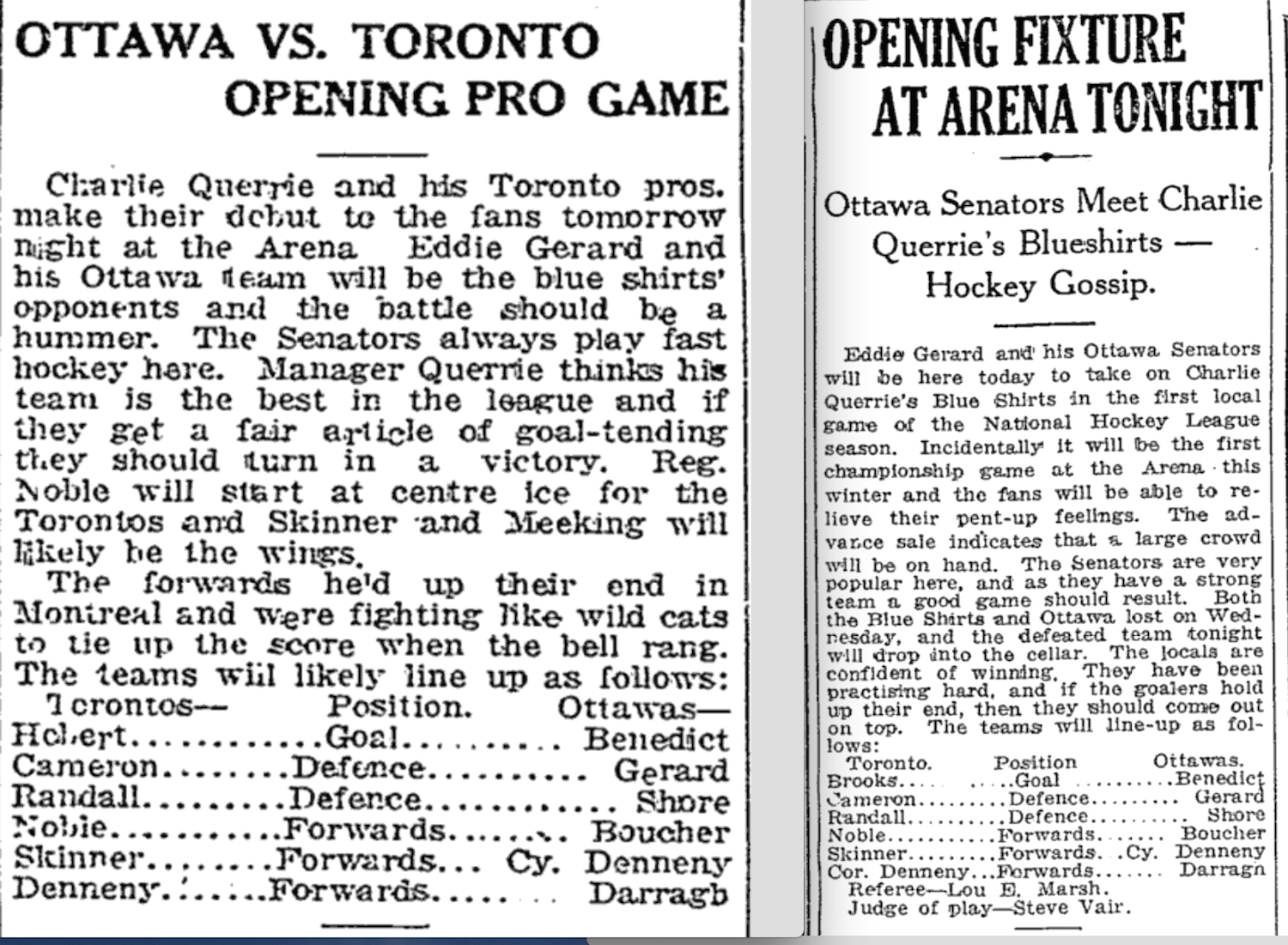

Ad for Toronto’s NHL opener in The Globe on December 22, 1917. Pre-game coverage of Toronto’s NHL opener in The World on December 21 and 22, 1917.

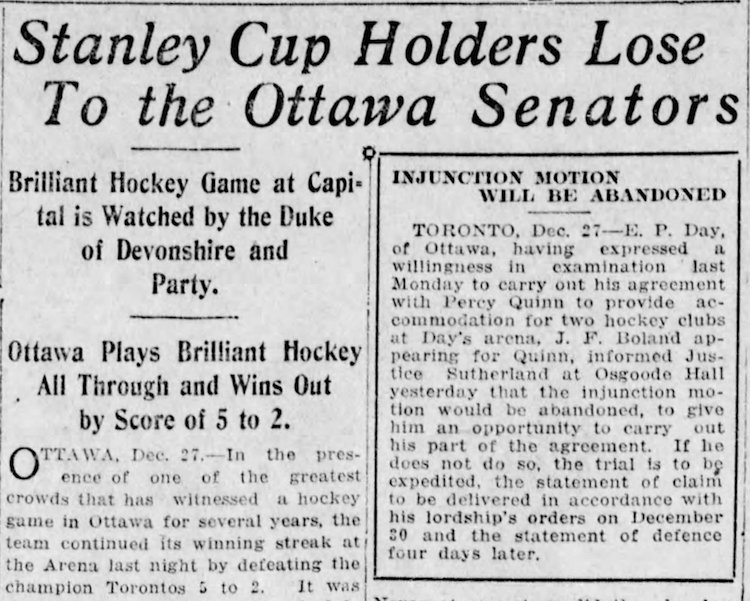

Pre-game coverage of Toronto’s NHL opener in The World on December 21 and 22, 1917. Hockey fans in 1917 would have noted little difference between the NHA and the NHL.

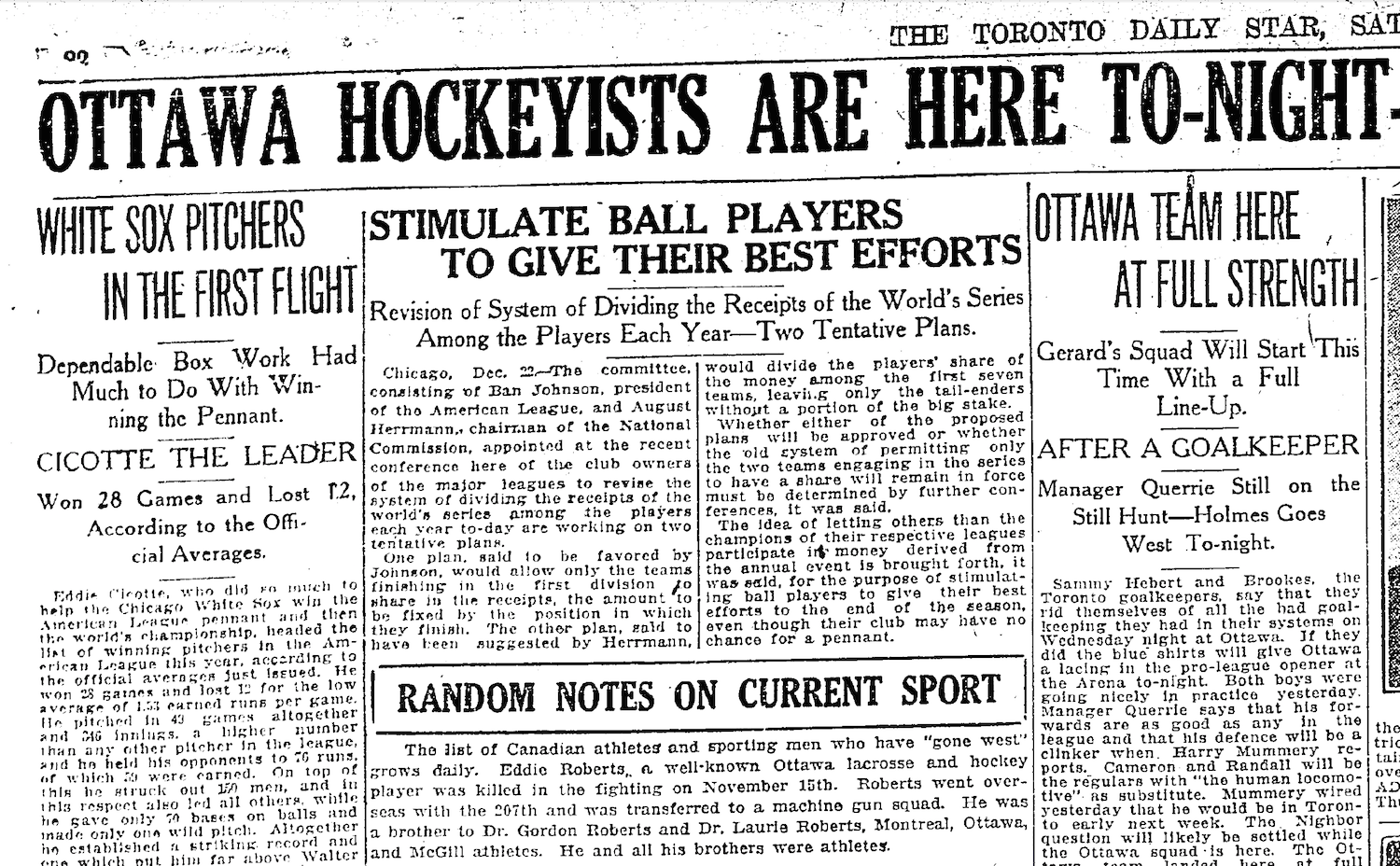

Hockey fans in 1917 would have noted little difference between the NHA and the NHL. The death of Eddie Roberts is noted in Random Notes on Current Sports.

The death of Eddie Roberts is noted in Random Notes on Current Sports.