I don’t really have a good explanation for why I like the early history of hockey as much as I do. I still watch plenty of the current game, but as I often say to people when they ask me, I can tell you with a lot more authority why the Kenora Thistles won the Stanley Cup in 1907 than I can tell you why I think a team might win it this year.

Thistles captain Tom Phillips (who I’ve written about extensively for the Society for International Hockey Research and mentioned a couple of times on this site) is one of a handful of early era Hall of Famers (along with Art Ross, Frank & Lester Patrick, Cyclone Taylor, Newsy Lalonde, Joe Hall and Fred Whitcroft) that I find fascinating.

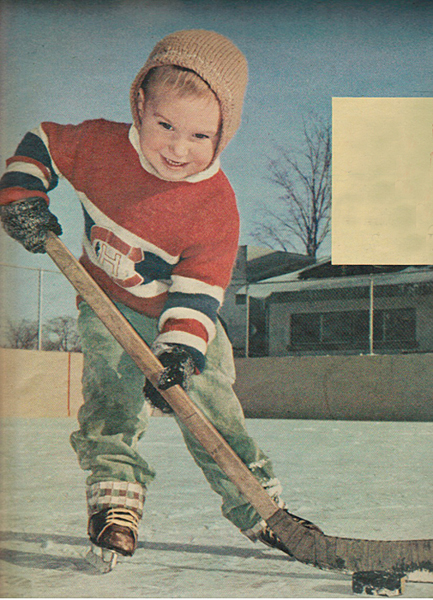

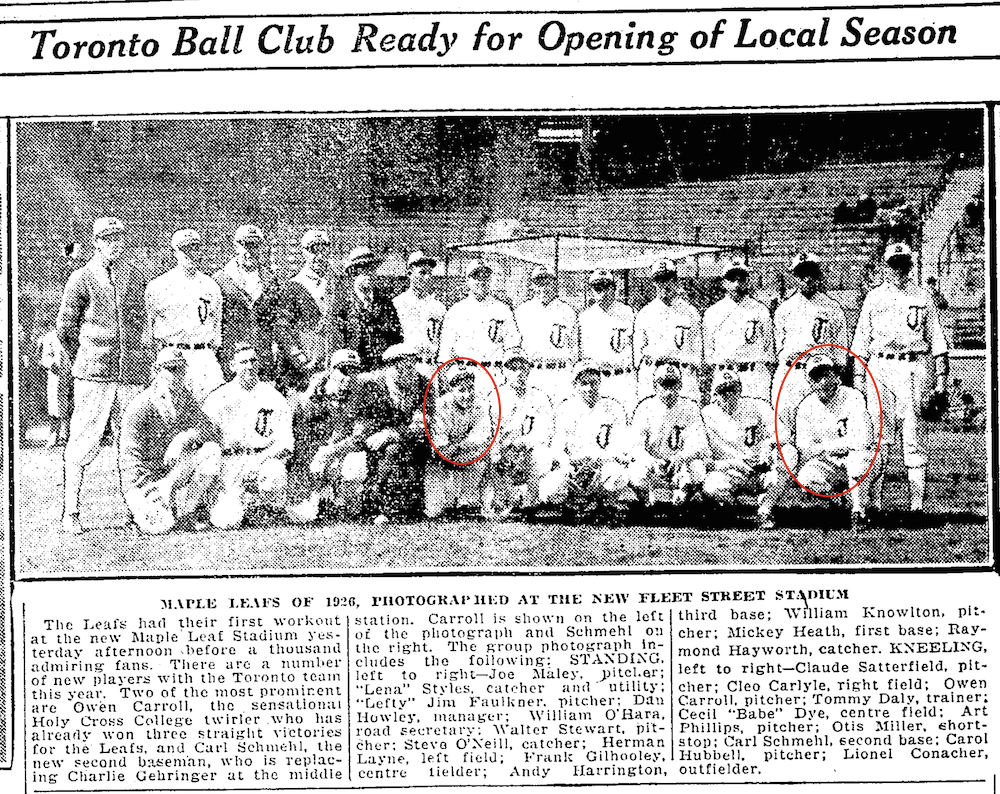

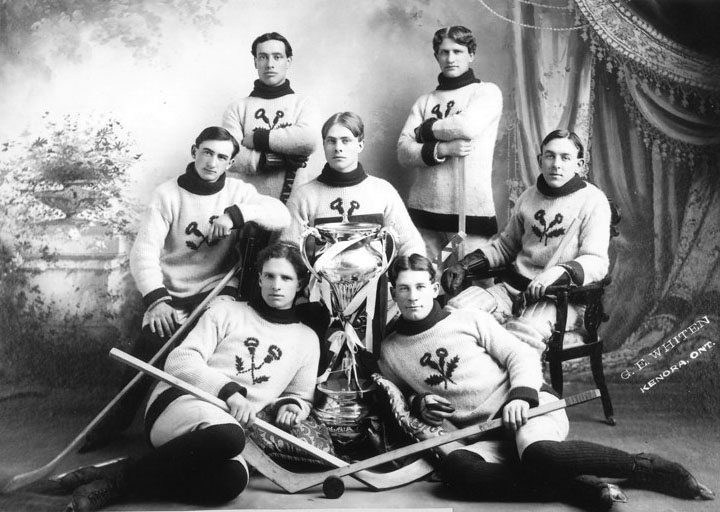

Tommy Phillips reclines to the right of the huge trophy symbolizing the senior championship of the Manitoba Hockey League, which the Kenora Thistles won for the

second of three straight seasons in 1905-06.

Tommy Phillips was the Sidney Crosby of his day. In his era, he was considered one of the top two players in hockey. If you were from the West, you’d likely pick him; while Easterners were more partial to Frank McGee. McGee was a goal-scoring machine with the Ottawa “Silver Seven” who was famously blind (or at least had his vision impaired) in one eye. Turns out, Tommy Phillips was playing under a pretty severe handicap too.

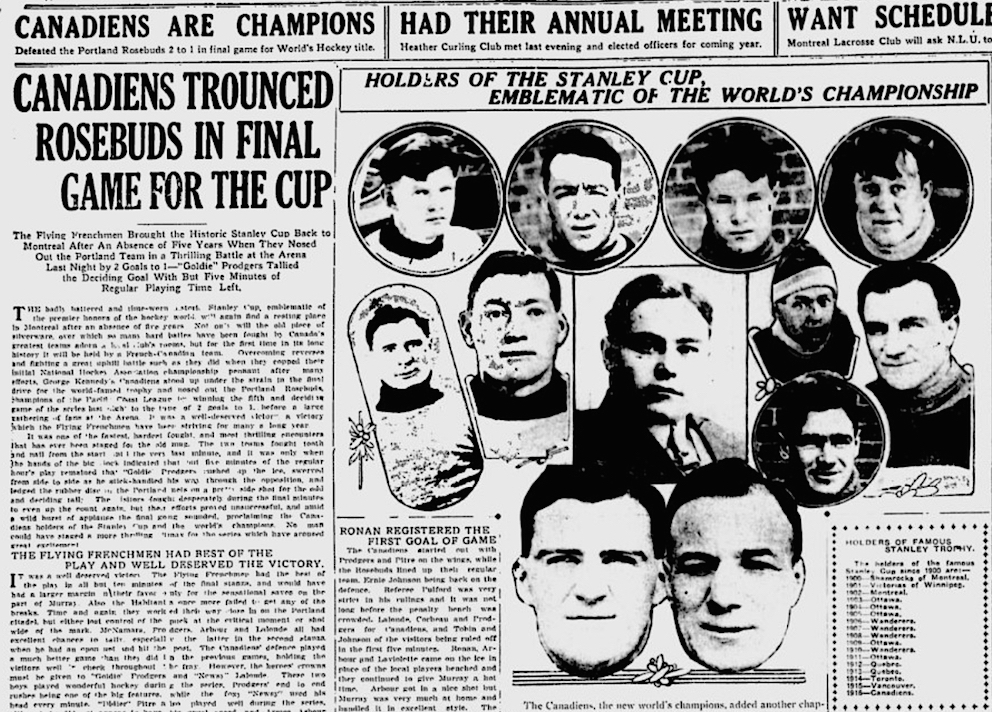

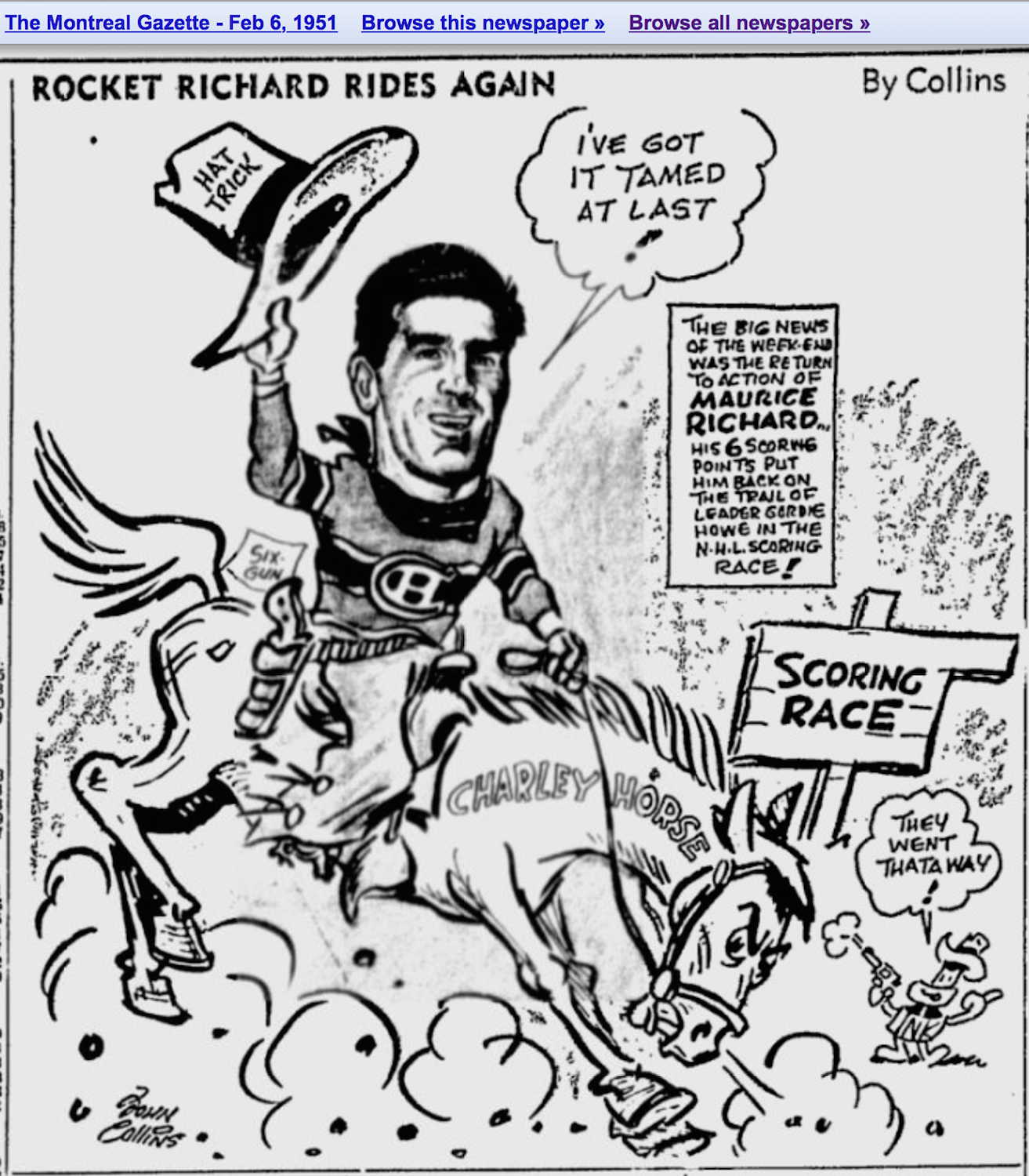

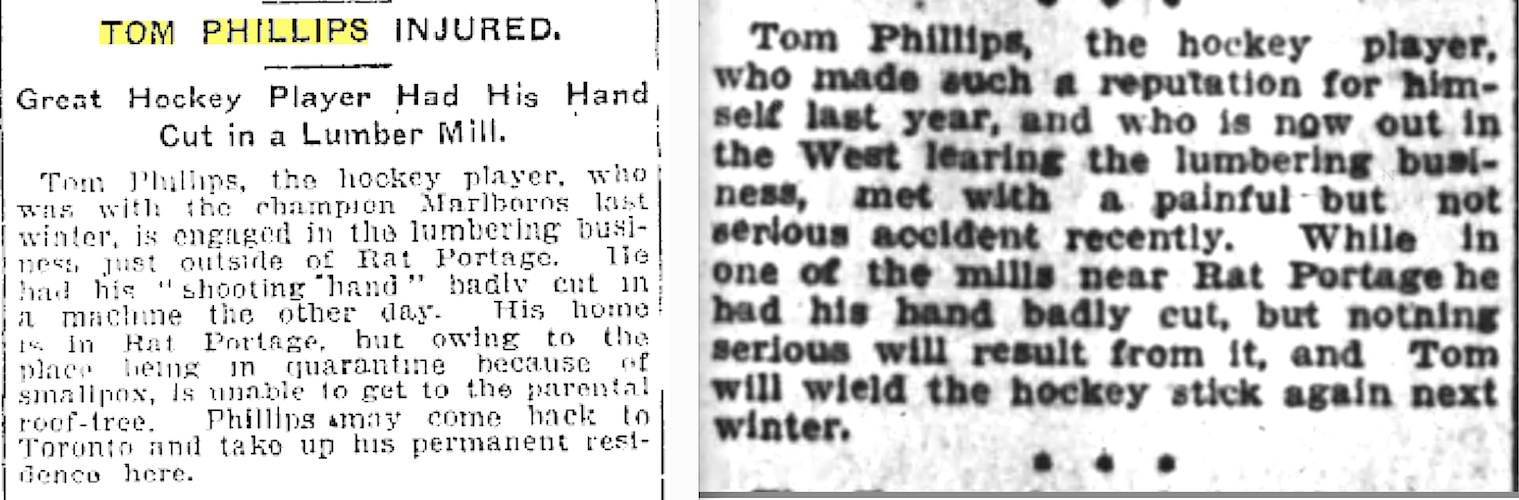

Articles from the Toronto Star on August 4, 1904 and the Ottawa Journal one week later.

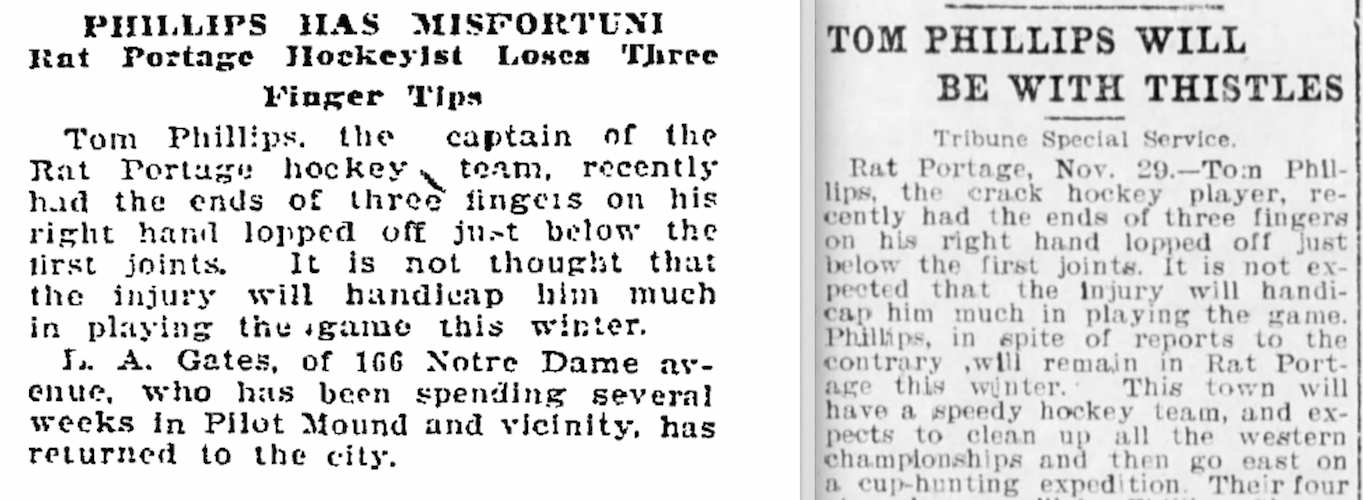

Several years ago, I came across the Toronto Star newspaper clipping above claiming that Phillips had injured his hand while working in a lumber mill near his hometown during the summer of 1904. Recently, I went searching for more stories about this, and discovered a couple of clips that make the injury sound a lot more serious than just a bad cut. It seems Phillips had actually lost parts of three fingers on his right hand.

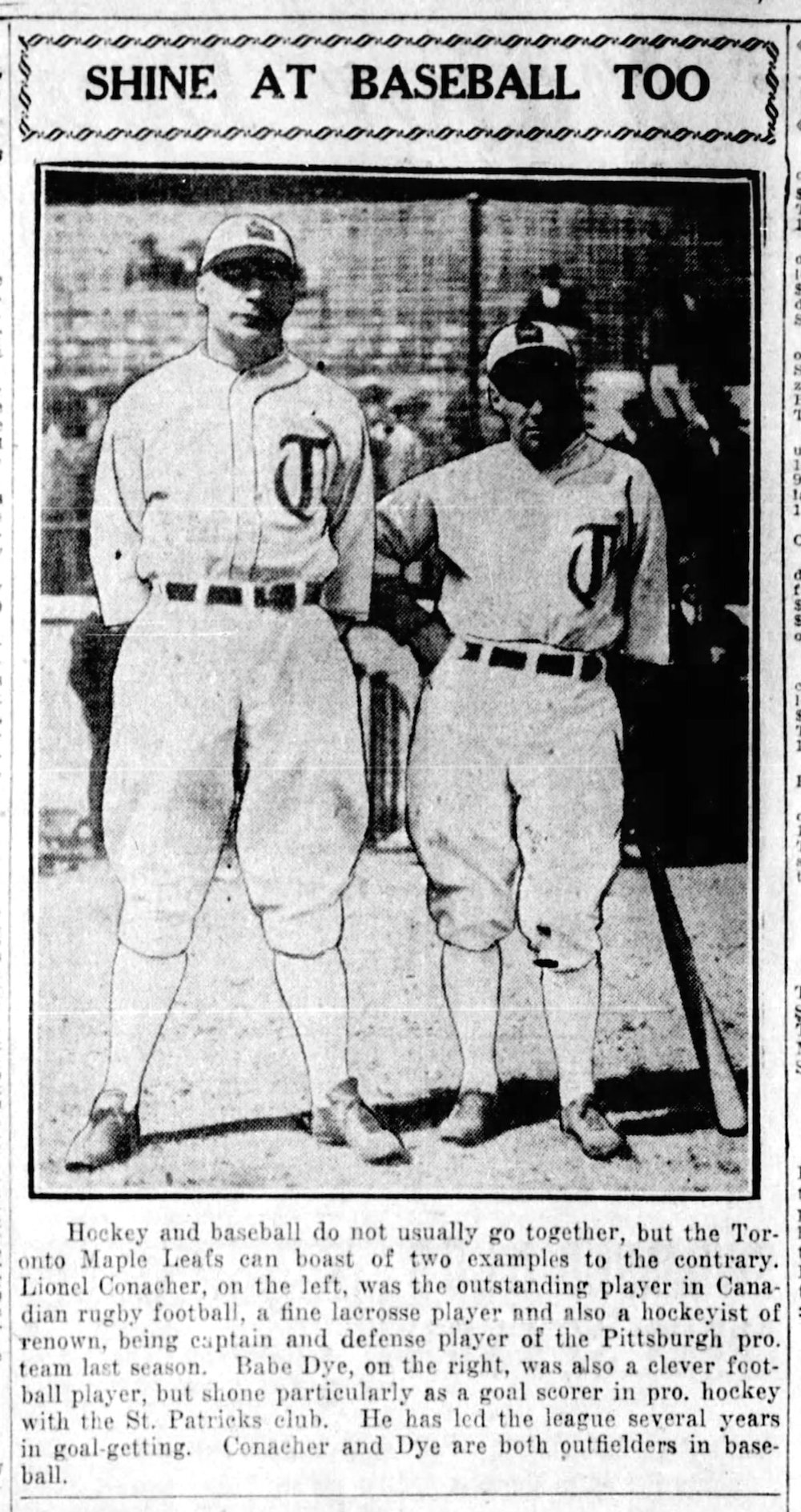

Articles from the Winnipeg Morning Telegram and Winnipeg Tribune on November 29, 1904.

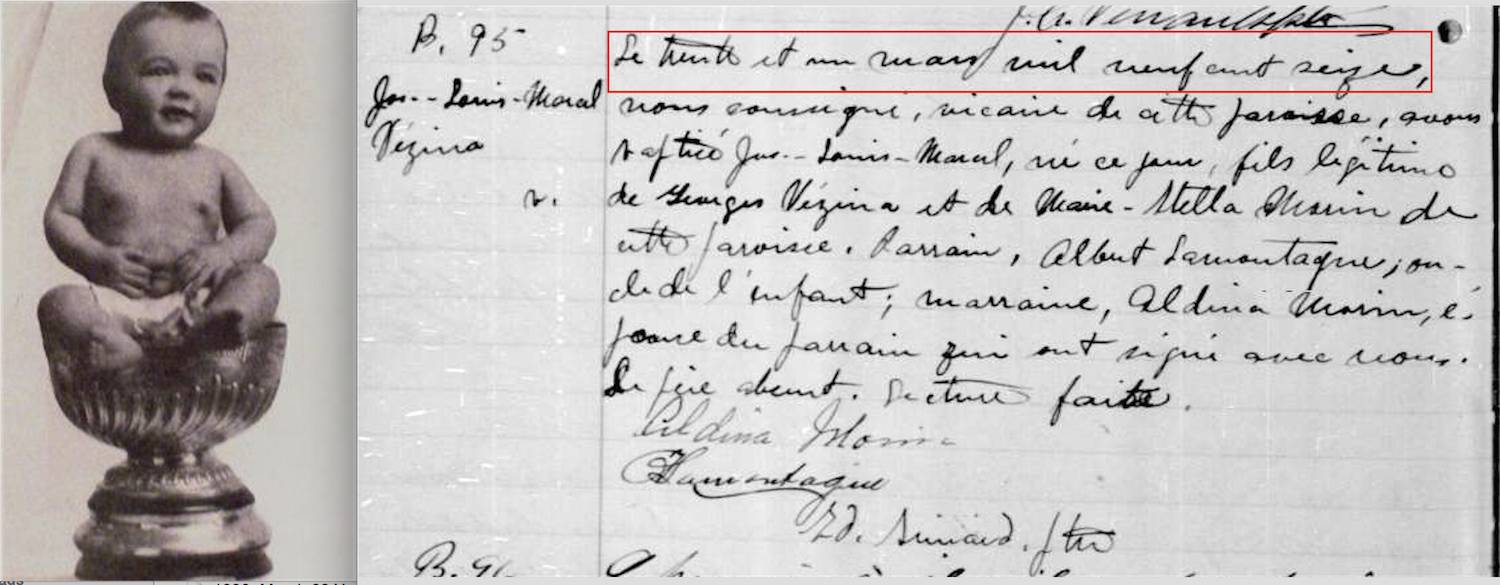

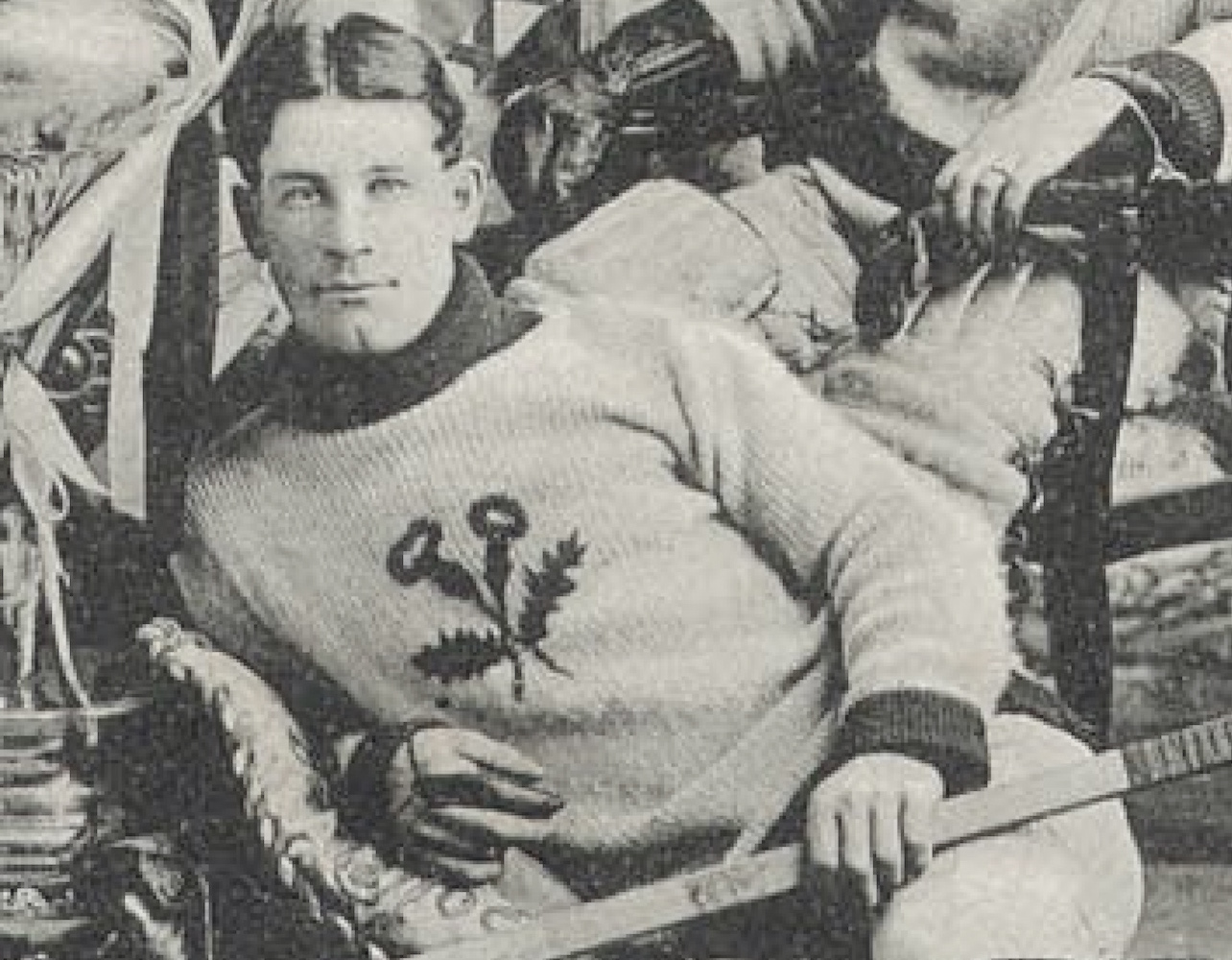

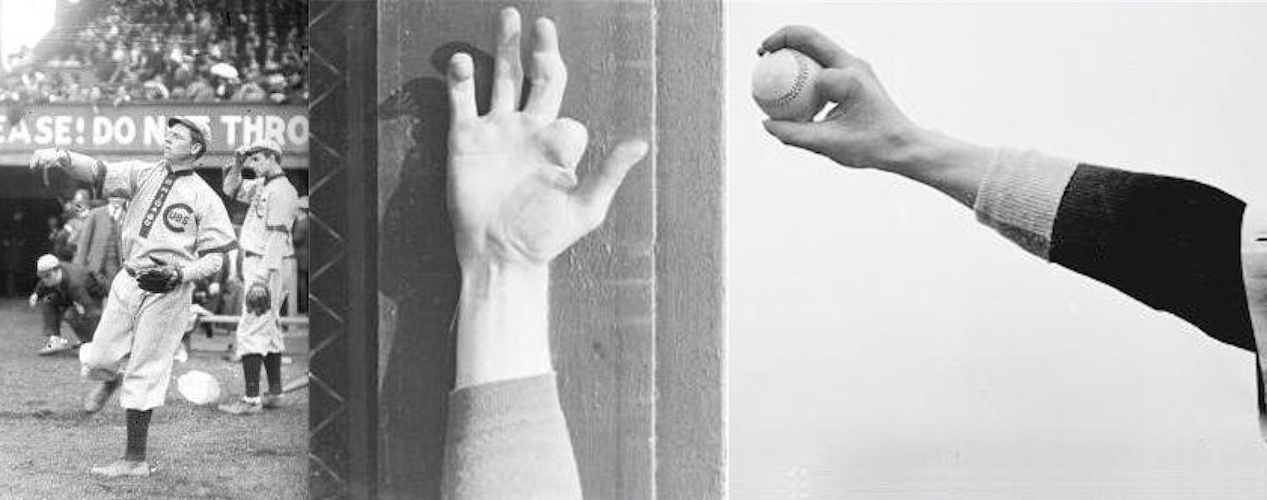

Look again at the team picture above, and then have a look at the (slightly blurry) blow up below. Clearly, there’s something up with Phillips’ right hand.

There appears to be a strap leading to what is either a protective cover or some sort of artificial right index finger. His pinky as well as the finger next to it (which certainly seems to be abnormally short) both look to be similarly protected or replaced.

Unlike Hall of Fame baseball pitcher Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown of the same era – who had his right hand mangled in farm machine as a youth but learned to grip a baseball in such a way that it gave him an exceptional curve ball – it’s hard to believe that Tom Phillips’ accident gave him any sort of physical advantage.

Yet given that Phillips had the best years of his career from 1904-05 through 1907-08, he was clearly able to perform at an extremely high level despite his injury. He may not have been Bobby Orr on wounded knees, or Mario Lemieux beating cancer, or Sidney Crosby coming back from a concussion, but it’s still pretty remarkable.