As many of you reading this are already aware, I have a biography called Art Ross: The Hockey Legend who Built the Bruins due out this fall with Dundurn. Several stories that have appeared on my web site already have been the result of items I came across while researching Art Ross. More will be coming in the months leading up to the release in September, but this is the first real “commercial” for the book.

In March of 1970, Eddie Shore was in New York to receive the Lester Patrick Trophy for his contributions to hockey in the United States. He was presented with the award at Toots Shor’s Restaurant on the evening of March 9, 1970, but had held court with reporters at the Madison Square Garden press lounge during the afternoon. Shore was asked about the current star of the Bruins defense, Bobby Orr.

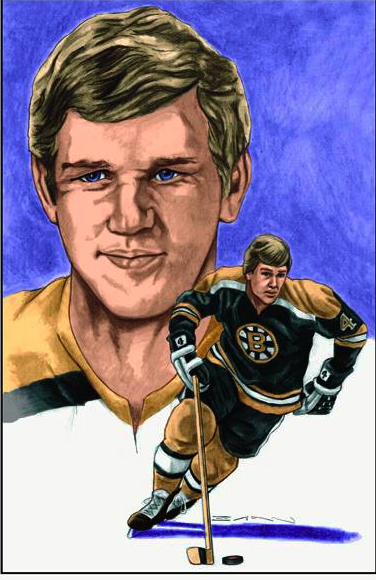

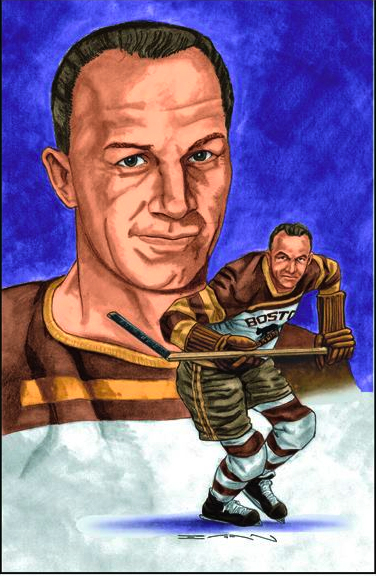

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on Facebook.

“I haven’t had that much chance to see Orr play,” Shore admitted. “But when I first watched him as a junior, I said he would be outstanding. He’s obviously a fine skater but I think the best thing about him is his ability to adjust his own speed to anticipate the speed of the players whom he is giving a pass.”

Those present wondered how Orr would have fared in Shore’s era, and somebody wondered if Shore had ever thought that a defenseman might win the NHL scoring title, as Orr was en route to doing.

“Yes, I believe one might have,” Shore said with a sly grin. “But maybe I shouldn’t really be specific.” Tom Fitzgerald, writing in the Boston Globe, noted that it didn’t take much urging for Shore to elaborate.

Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

“Sure, I think I might have done it myself at least one year, but it would have cost me money. You see, when I carried the puck in, if I shot instead of passing, Art Ross had a standing fine of $500. It would have been too expensive.”

Ross had been dead for nearly six years at this time, so he wasn’t there to comment. Still, he’d told a very different type of story to Lester Patrick’s sons, Lynn and Muzz, back in 1958, which was reported by Dave Anderson, then of the New York Journal-American:

“When Leo Dandurand owned the Canadiens,” Ross explained, “he was in Chicago one night and we were there. So I invited him to sit down on the bench with me. After a while, I said to him: ‘Leo, would you like to see Shore score a goal?’ And he said: ‘What?’ So I asked him again. ‘Do you want to see Shore score a goal? I’ve got a signal.’ Without waiting for him to answer, I caught Shore’s eye and gave him the signal.”

Ross pointed his right forefinger, then rotated it clockwise; all the time holding his hand near his hip so as not to be conspicuous. Then he continued:

“Shore got the puck, took off, and wham! Goal! So Dandurand looked at me and said: ‘Can you do that anytime you want?’ ‘Sure,’ I told him, ‘and not only that, he’ll keep doing it until I tell him to stop.’ So, I caught Eddie’s eye again and give him a wave. That was the signal to stop. I didn’t want to overdo a good thing.”

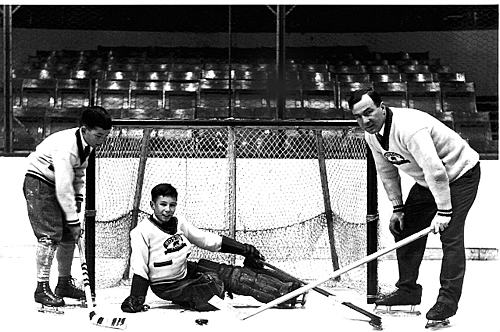

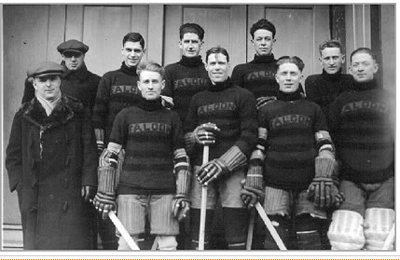

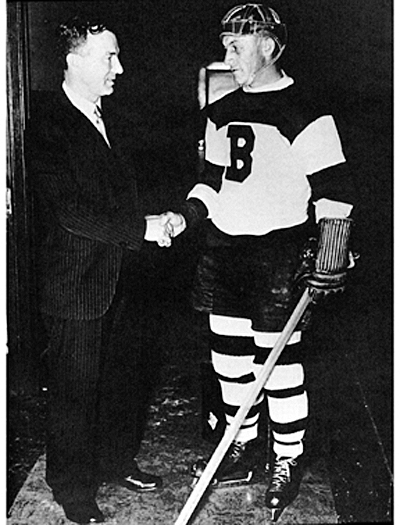

Photo courtesy of Art Ross III

Could either Shore’s or Ross’s tale be true? It’s difficult to say. Sportswriters for a long time rarely let the facts get in the way of a good story, and there’s little reason to believe the subjects of those yarns were any better!