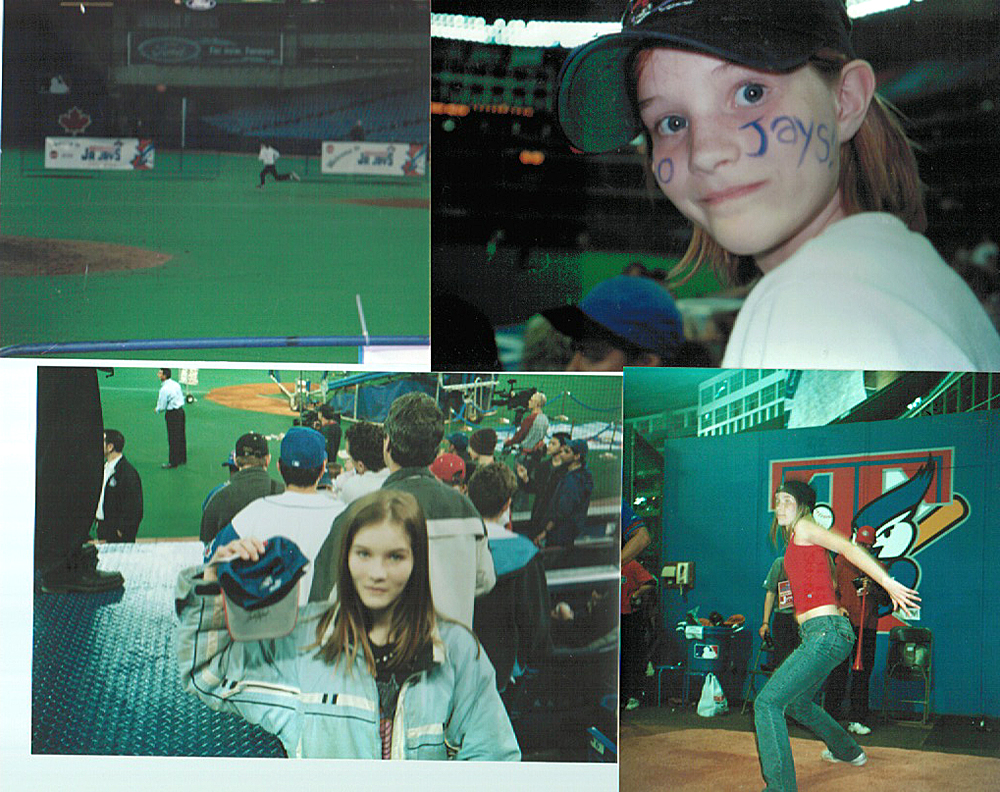

This Friday, my brothers David and Jonathan, Jonathan’s son Jorey, and I will be making the short road trip to Detroit to see the Maple Leafs play the Red Wings. We’ve made a couple of trips like this before, but in the summertime to see the Blue Jays and to visit Cooperstown for Roberto Alomar’s induction.

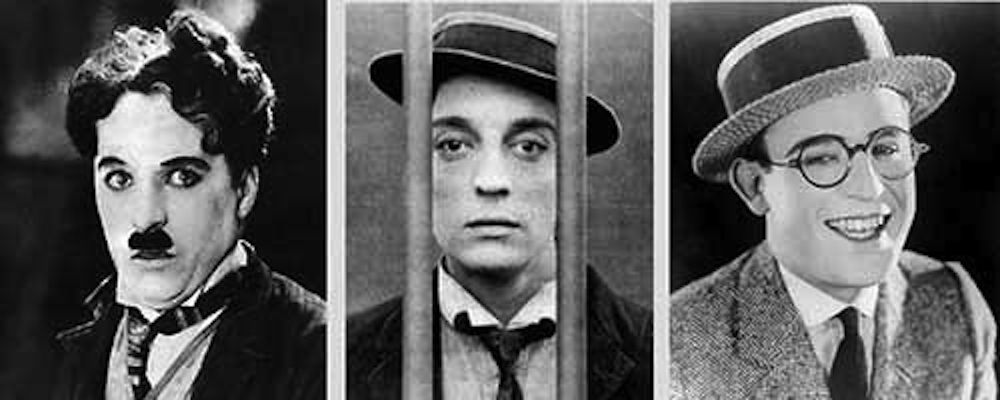

The first picture I ever took with my iPhone. David,

me, Jonathan, and Jorey at a Jays game in 2016.

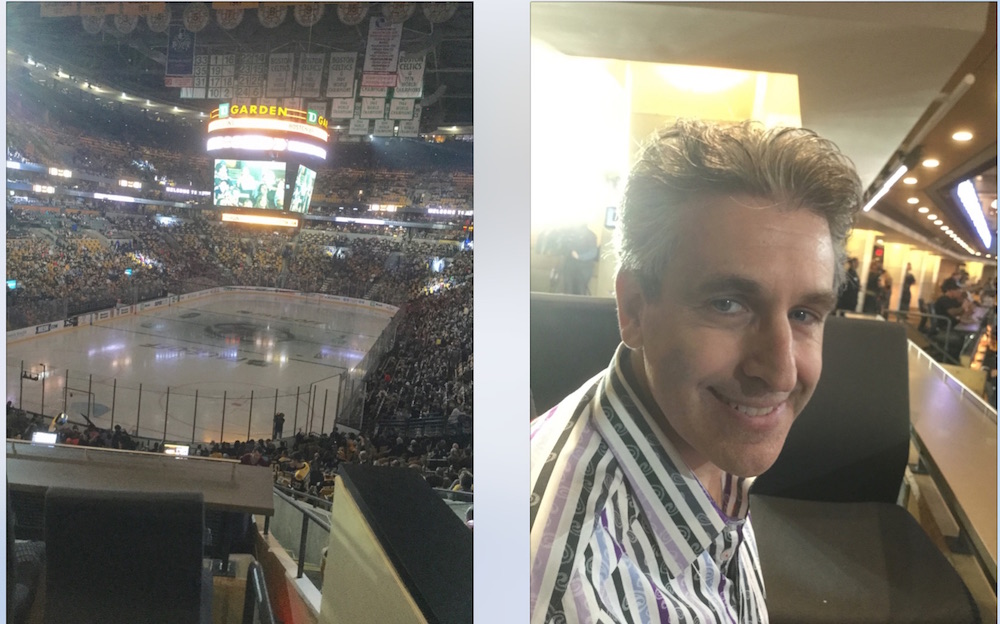

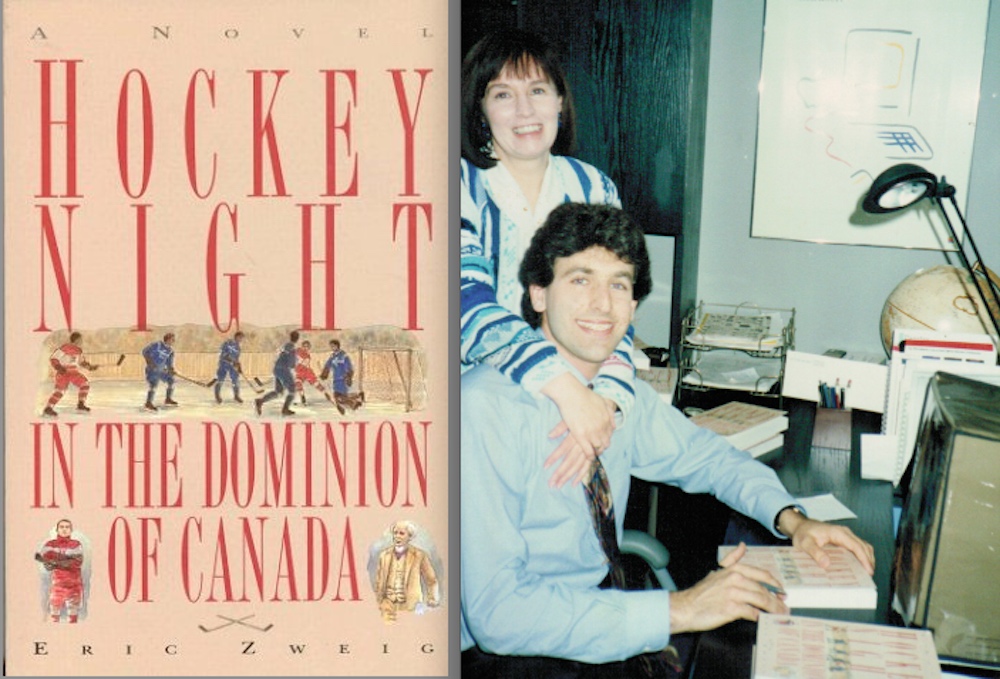

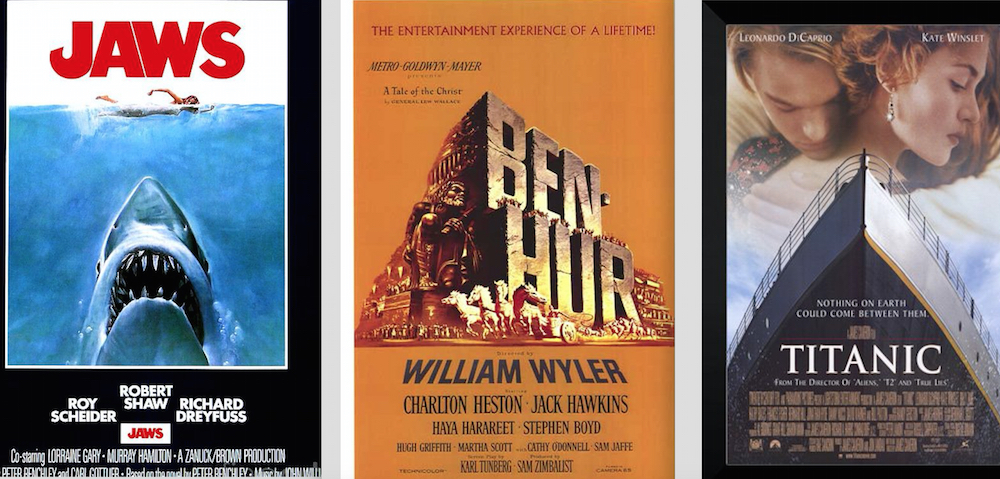

For me, I’m pretty sure this will be the first time I’ve seen the Maple Leafs on the road. First time I’ve seen them live anywhere since Barbara and I went to a game so long ago that I can’t remember exactly when except that it was at least 2006. It was Montreal at Toronto and she was dressed in a vintage Canadiens sweater, me in vintage Maple Leafs. It’s hard to believe, but I think the last time I was actually at a hockey game anywhere was in the fall of 2015. Barbara and I were in Boston and the New England Sports Network (NESN) hosted us in a small private box next to their set where I was to be interviewed about my book on Art Ross during the first intermission.

Photos by Barbara from our box at the game in Boston.

This is my second trip of late. Earlier this month, I spent two weeks in Florida. The weather was perfect, and, as I’ve been telling people, the biggest decision I faced each day was “should I get my tan on the beach or by the pool?” (Sure beats the current dilemma of “should I shovel the driveway now or wait until it’s completely stopped snowing!”)

I rode down with my friend Jeff, who has a place on Anna Marie Island, near Sarasota. He was a great host, and I think I was a good guest. So many people had been telling me after Barbara died that I should get away for a while and lie on a beach somewhere. I’m not sure I actually would have if Jeff hadn’t offered. It really was a wonderful break.

Me on the street in Ybor City, Tampa, about two weeks ago.

Barbara loved to travel. Me, not so much. And, really, for the stupidest of reasons. I used to say, “I don’t want to go away anywhere if I have to come back.” By that, I meant you spend a week or two away, and then you come home to a pile of bills, maybe or maybe not some household disaster that needs your immediate attention, and definitely a ton of work you need to catch up on. Two days back, and it’s like you were never away. So, why bother? And, let’s be honest, I was always worried about spending the money…

These days, you can pay your bills online and I don’t really have any work to catch up on. (Though I did just recently agree to write some short hockey pieces for a friend whose work I admire.) Even so, as great as the Florida trip really was, it did make me realize all over again how alone I am when I’m at home. (Don’t worry too much; I’ve got lots of friends looking out for me!)

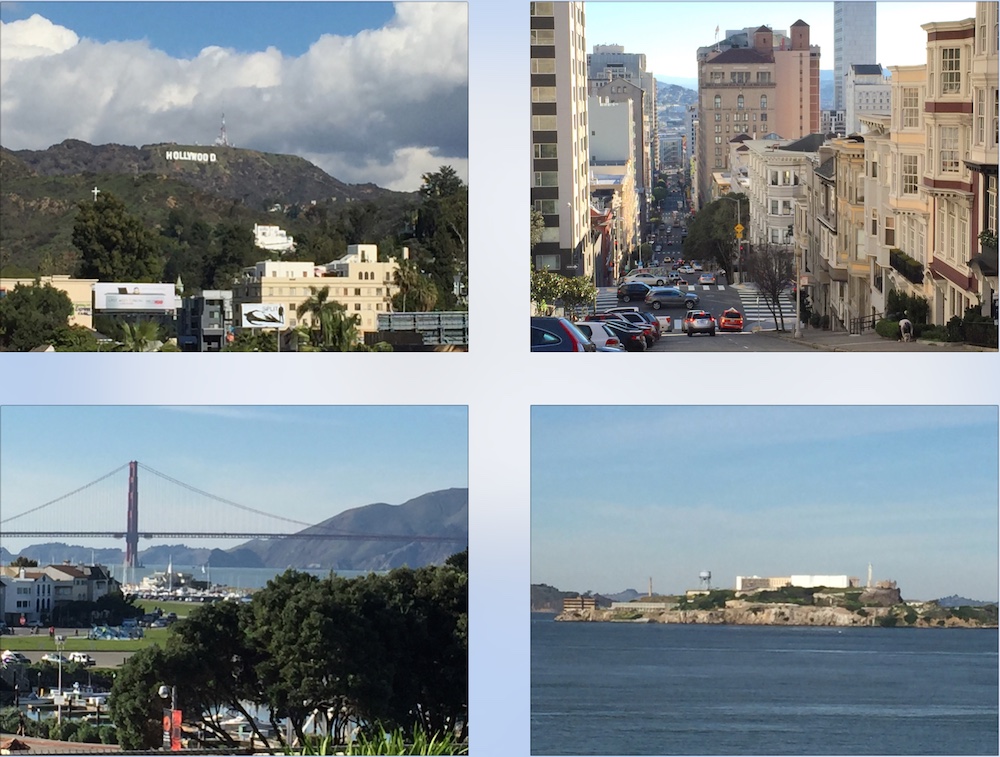

It felt nice to get away, but it was strange to be on vacation without Barbara. No matter how much I griped about it before agreeing to go somewhere, we always, always, had a great time. Didn’t matter where we went, or how long we stayed. Here are a handful of pictures from some of our trips over the years…

The last big trip Barbara and I took was to Los Angeles and San Francisco

two years ago right about now. I’d never been to L.A. before. We’d both

been to San Francisco, including on our honeymoon. This trip was a belated

20th Anniversary / early Barbara milestone birthday present.

We didn’t have to go far to have fun. The top picture is overlooking the Niagara River

at Lewiston during a weekend in Niagara Falls in 1993. The lower picture is an ostrich farm

in Prince Edward County (near Kingston) about 10 years later. It did NOT smell great!

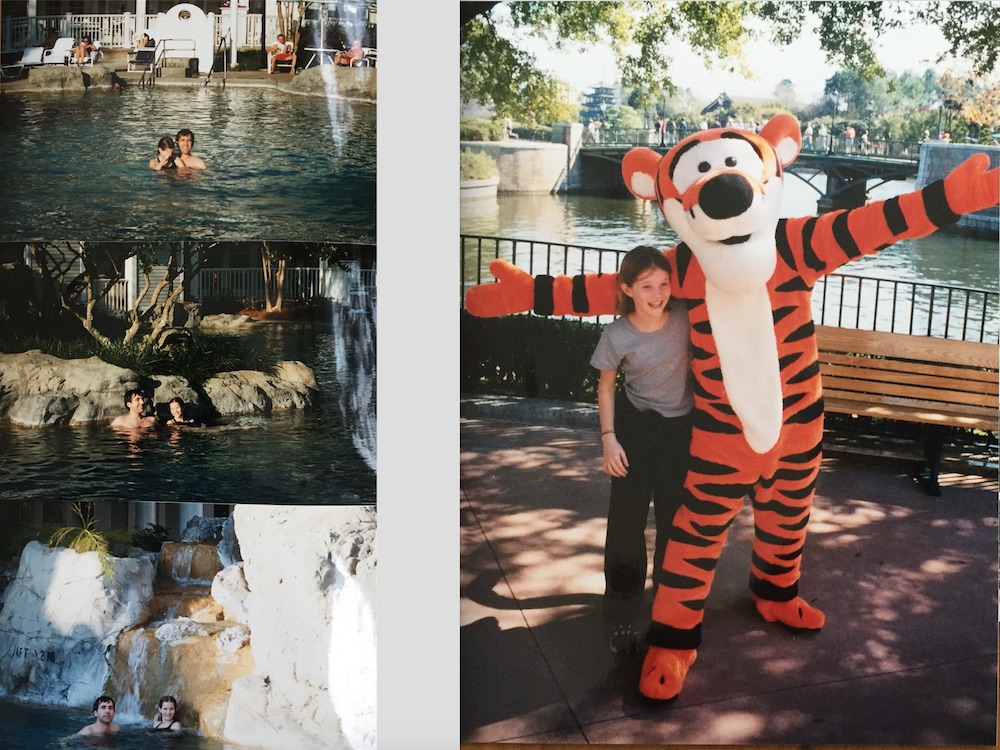

One of the best trips we ever had was taking Amanda to Disney World in 2000. That’s

me and Amanda in the pool at our hotel on the left and her with Tigger on the right.

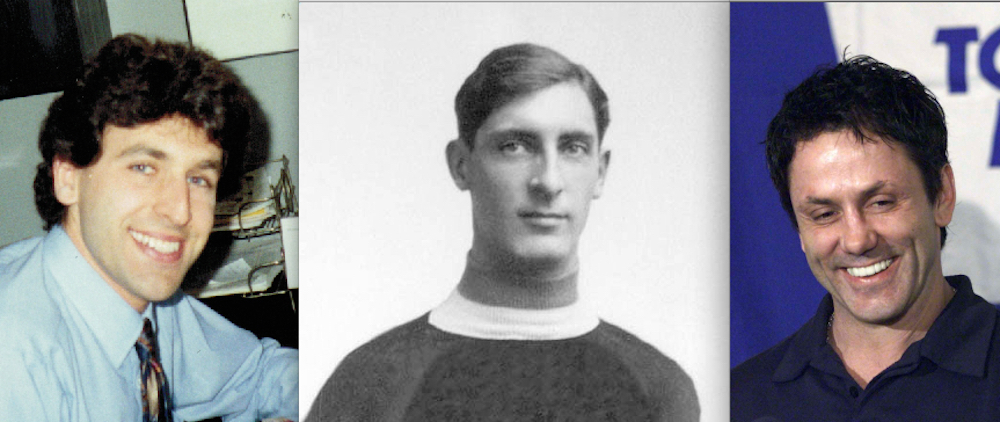

In the acknowledgements to my Art Ross book, I thanked his granddaughter

Valerie for saving Barbara and me from the worst hotel we ever almost

spent the night in near Williamstown, MA. This is where Valerie took us instead!

An earlier Ross-related trip. Us with our friend Kathy in Maine.

Chicago. Late in August, 2013. We loved it there!

Cheesy blue screen photos are us! The Red Baron’s Fokker triplane

and Air Force One at the U.S. Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio.

More blue screen fun! The George C. Page Museum at the La Brea tar pits on our

Los Angeles trip. The polar bear is actually real! (Or was.) It’s at the Natural History

Museum in L.A. where we spent an afternoon on a pouring rainy day.

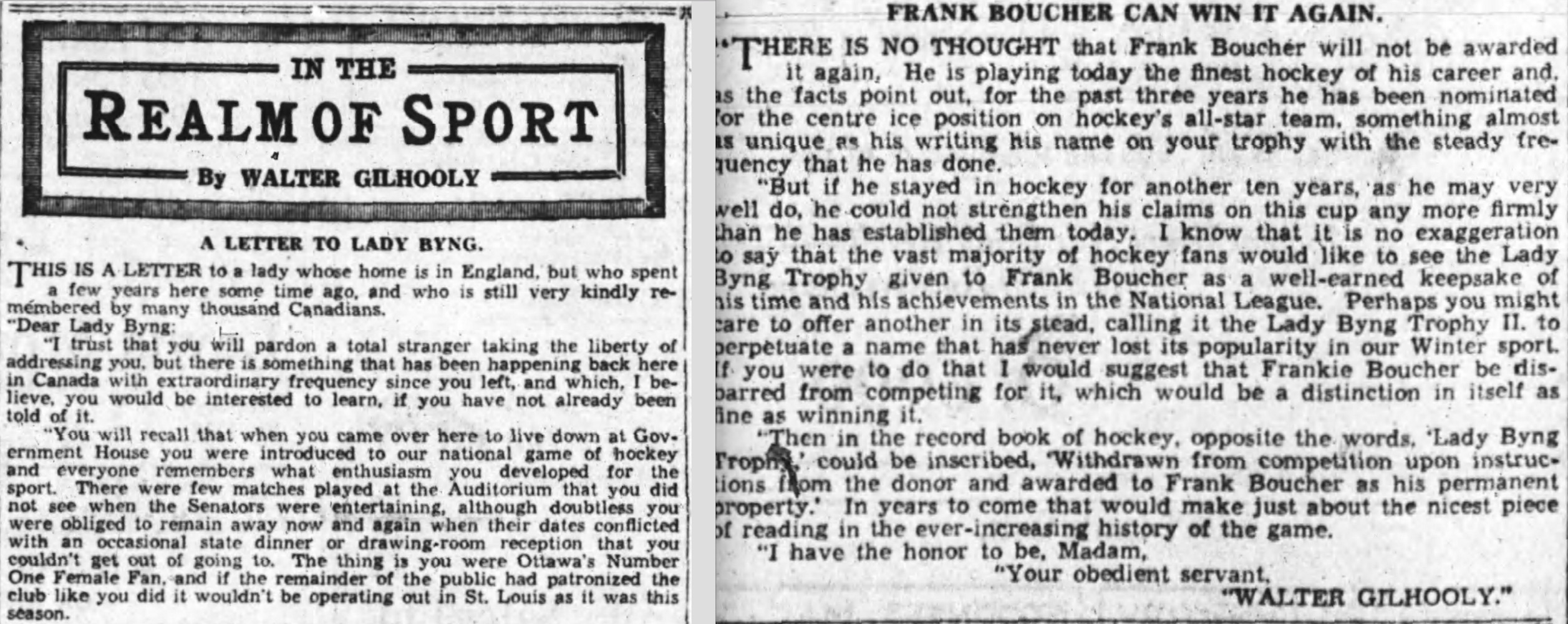

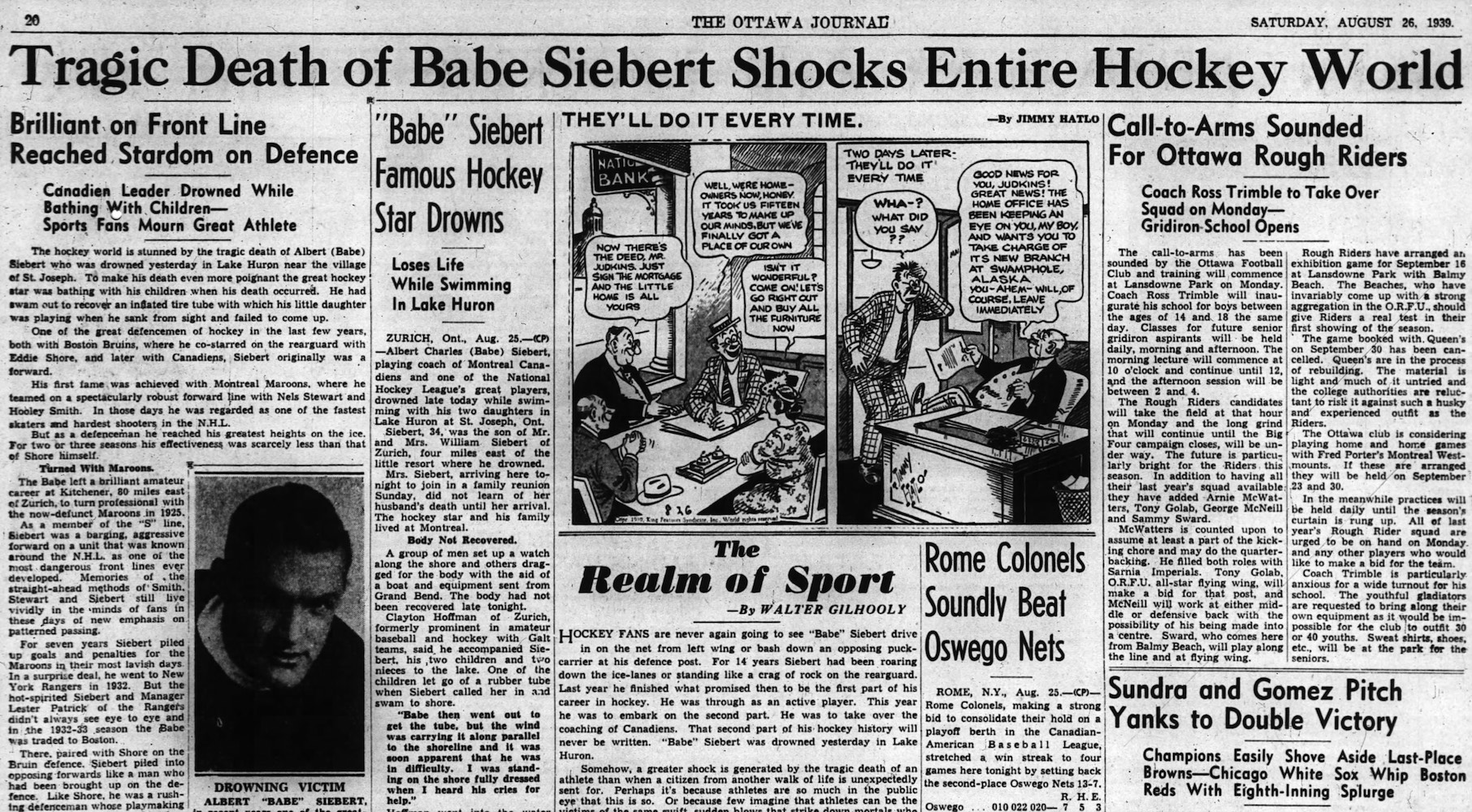

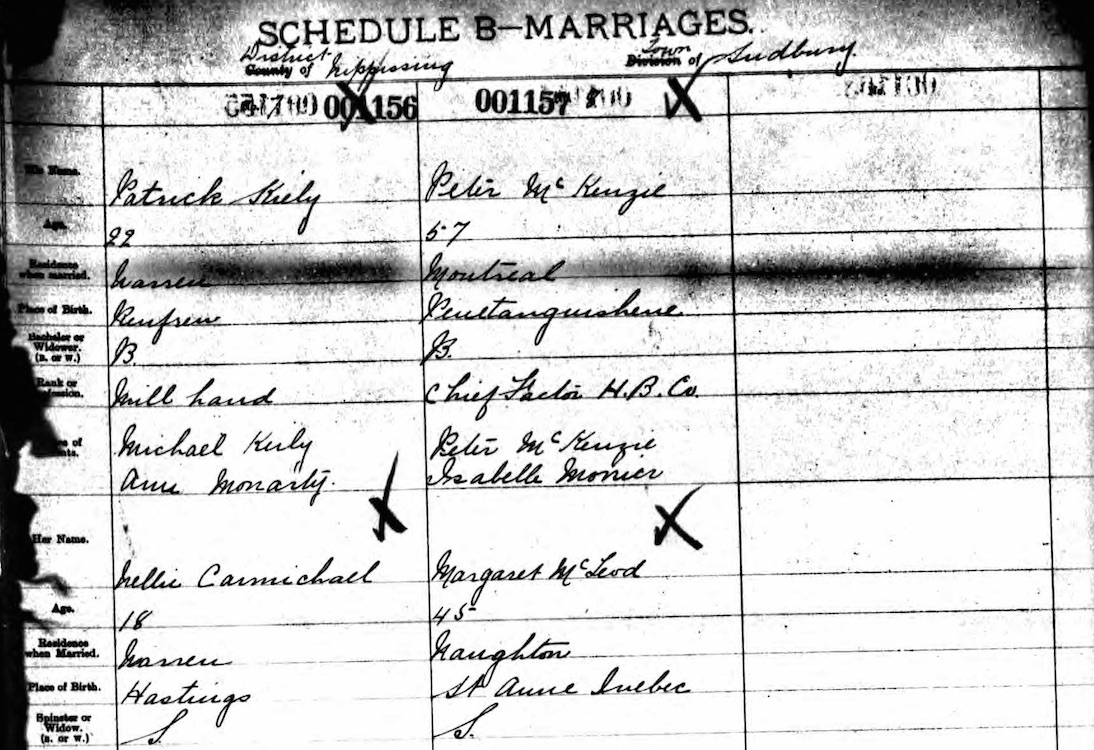

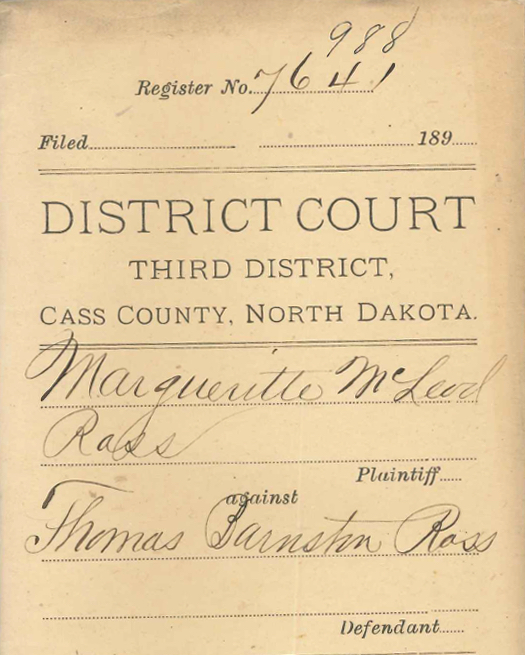

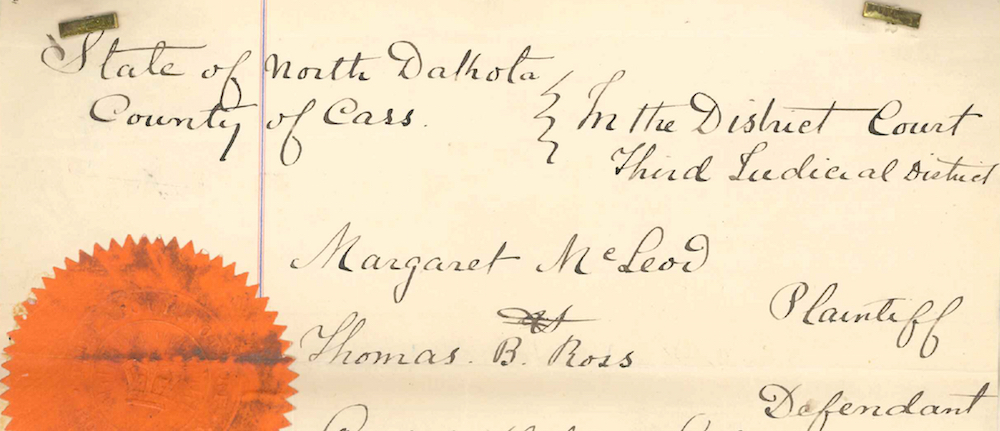

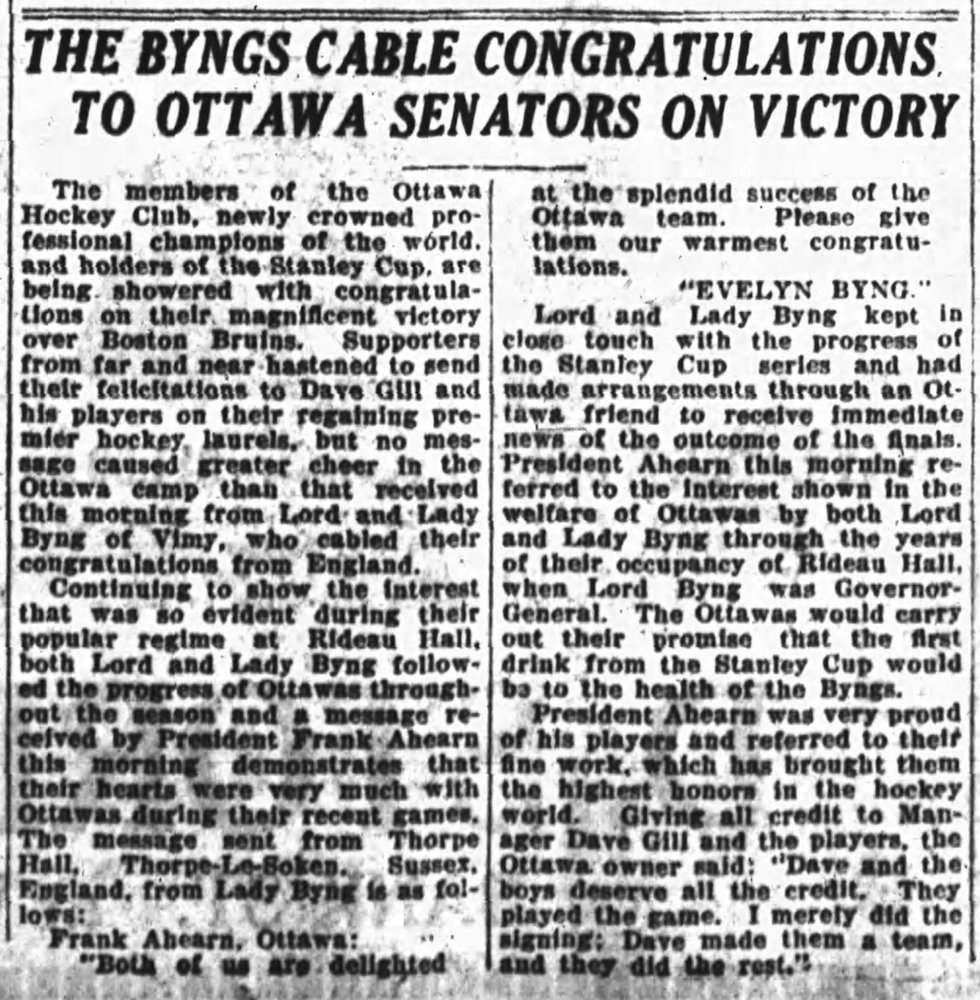

The Ottawa Journal, April 14, 1927.

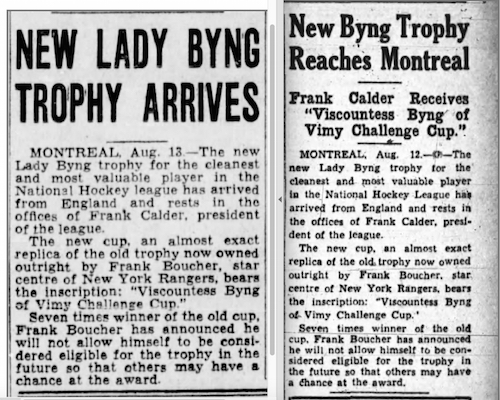

The Ottawa Journal, April 14, 1927. The Ottawa Journal, March 16, 1935.

The Ottawa Journal, March 16, 1935.