I recently had a very pleasant lunch with someone who asked me why I hadn’t been writing about hockey lately. His question was part of his larger concern for how I’ve been doing. As I’ve been saying all along, in the big picture, I feel that I’m doing fine. Or, at least as fine as can be expected.

So, my being depressed or not being depressed isn’t why I haven’t been writing about hockey. I actually have been writing quite a bit about hockey. I’ve written a new children’s book for Scholastic which will be out this fall, and I’ve done some other writing for a project by another friend whose work I’ve always admired. But the thing is, I’m kind of burnt out on hockey and still unhappy about certain ways in which the NHL Guide came to an end. So I haven’t bothered to write about hockey unless I’m getting paid. Still, I do find that I’ve enjoyed talking about hockey history when I’ve had the chance. So, I figured maybe it was time to post a story again. Because you can always find echoes of the past in anything new in hockey…

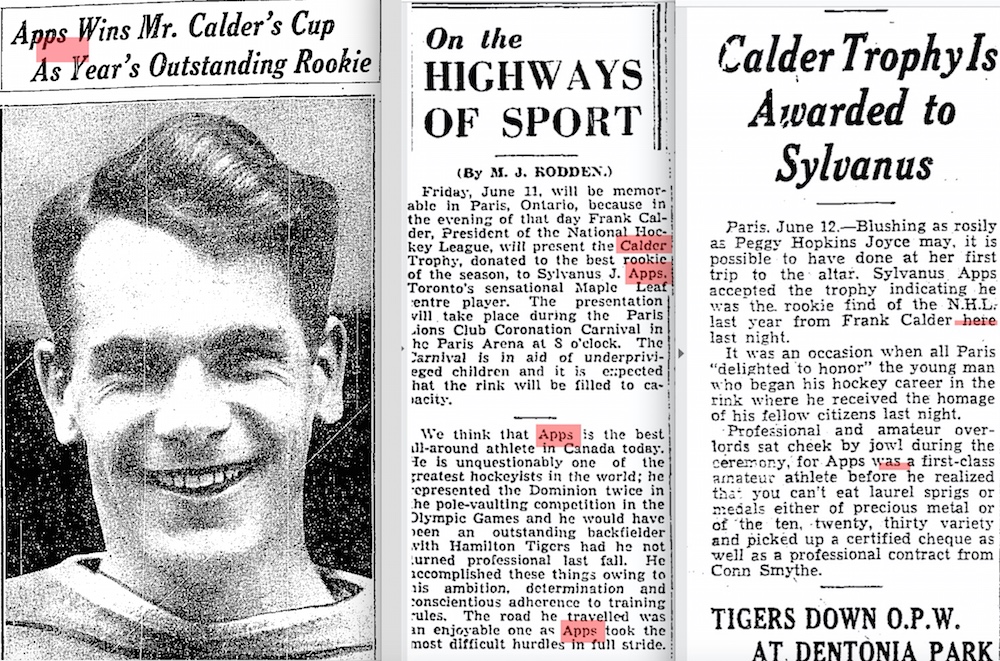

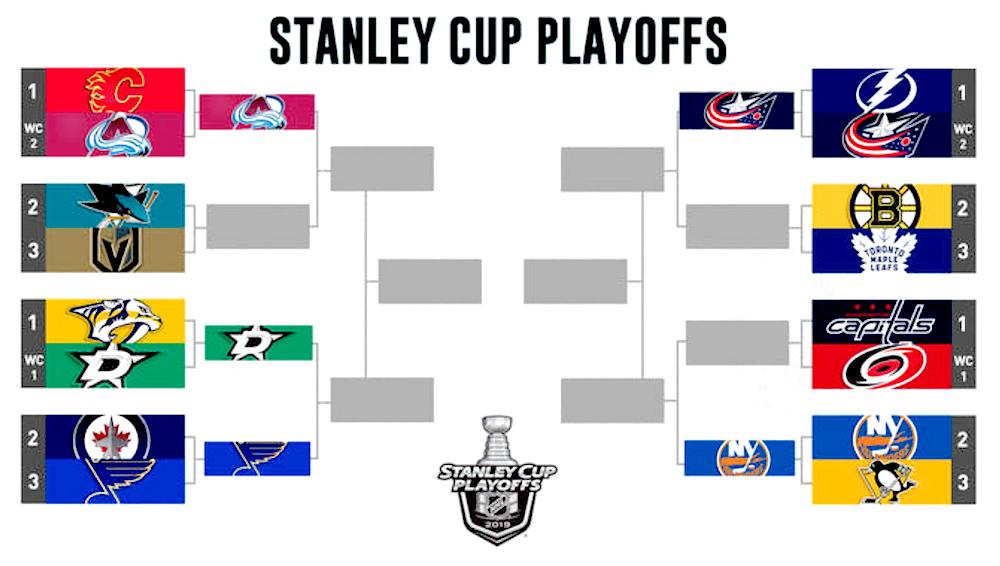

With upsets and more potential upsets abounding in the playoffs already, I read recently that this year marks the first time since NHL Expansion in 1967–68 that the top-ranked teams in both Conferences (or Divisions as it used to be) have been eliminated in the first round. The top teams in each Conference aren’t guaranteed to be the top two teams in the overall standings, but this year the Tampa Bay Lightning and the Calgary Flames did indeed rank 1–2 and yet both were bounced quickly.

First-round results from the 2019 NHL playoffs.

Even before expansion, such a double elimination was very rare. In the 25 years from 1942–43 through 1966–67, there were only two times when teams that finished 1–2 atop the six-team standings got knocked out in the first round of the playoffs. In 1964, third-place Toronto and fourth-place Detroit eliminated Montreal and Chicago before the Maple Leafs defeated the Red Wings to win the Stanley Cup. Prior to that, in 1961, third-place Chicago and fourth-place Detroit knocked off Montreal and Toronto before the Blackhawks (still written as Black Hawks back then) beat the Red Wings in the finals. That’s it.

Prior to the so-called “Original Six” era, the NHL featured between eight and ten teams playing in two divisions for 12 seasons from 1926–27 through 1937–38. Never in that time did the top teams from both divisions get eliminated in the opening round of the playoffs … but that was because it was impossible under the playoff formats at that time.

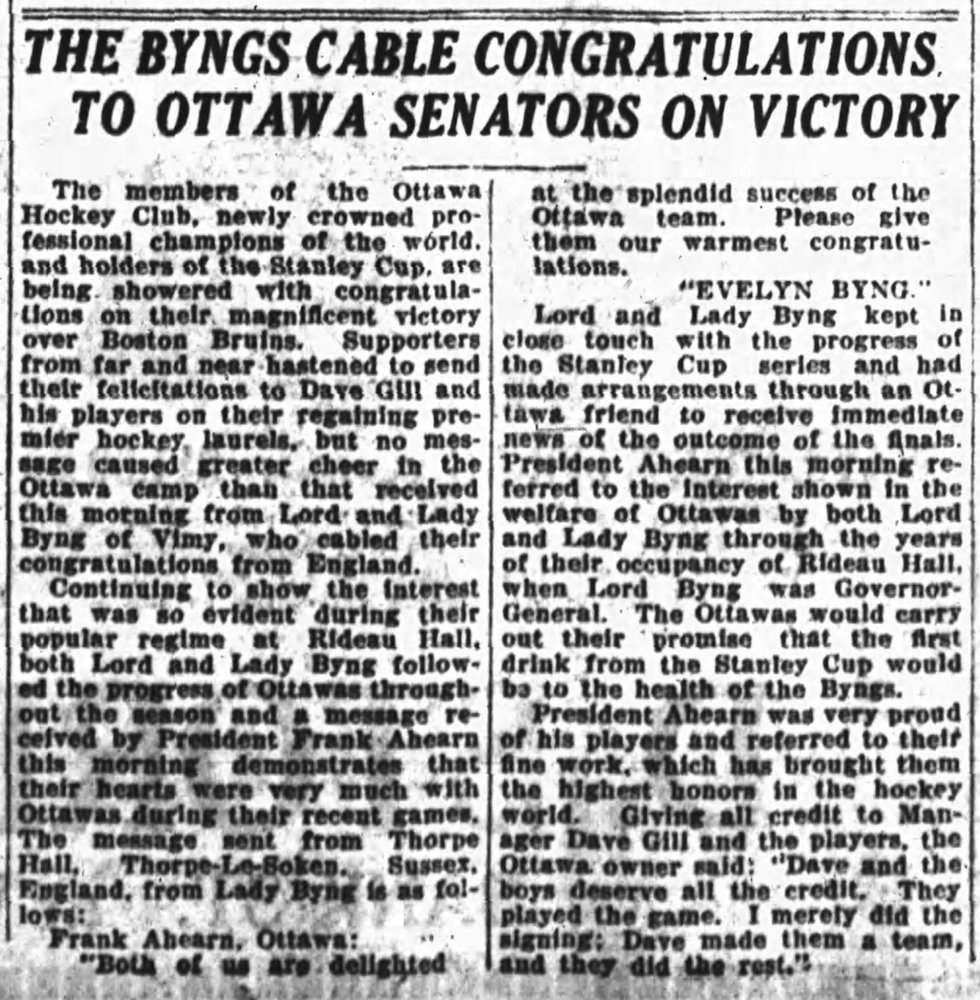

In 1927 and 1928, first-place teams got a first-round bye in a format very similar to the way the Canadian Football League playoffs have usually operated. In 1928, both first-place teams from the regular season (the Montreal Canadiens and the Boston Bruins) came off their short first-round layoff and were eliminated in the division finals. After pulling off those upsets, the second-place New York Rangers then faced the second-place Montreal Maroons in the Stanley Cup Final. The Rangers won.

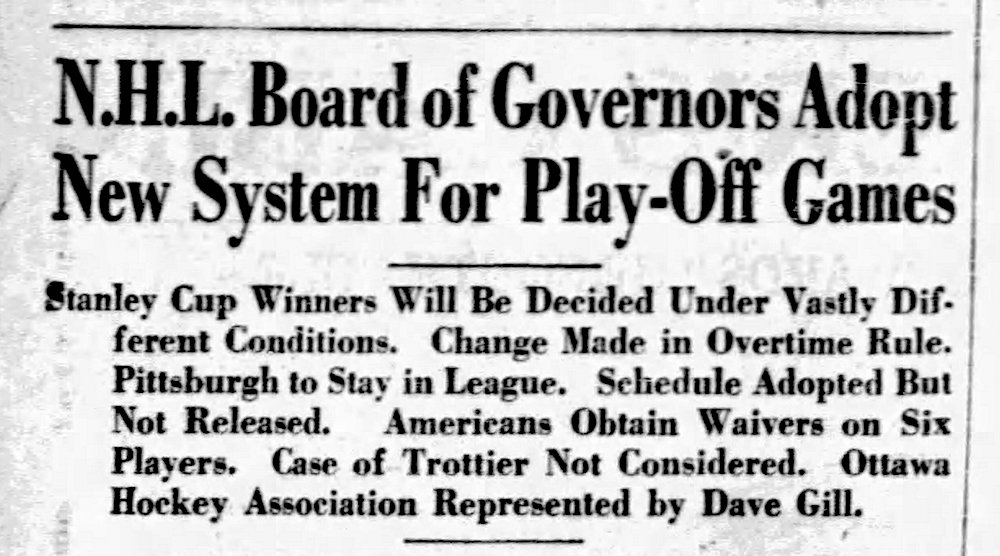

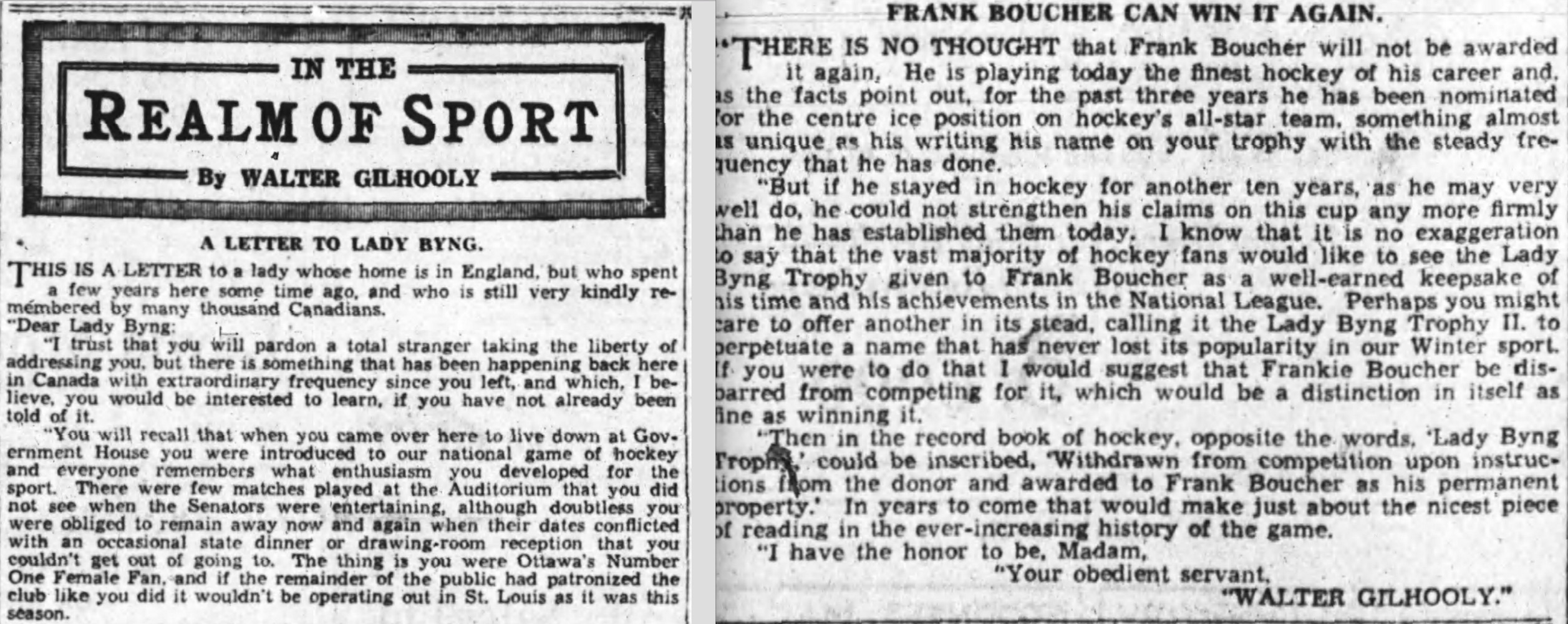

The Ottawa Citizen on September 24, 1928, reports on the new NHL

playoff format and other changes heading into the 1928–29 season.

There were those who wondered if the time off in the first round dulled the two division champions, and the NHL certainly wasn’t happy with the fact that neither first-place team got to play for the Stanley Cup. So Art Ross and Charles Adams of the Boston Bruins proposed a new playoff format that was accepted for the 1928–29 season. With a few tweaks, it would essentially remain in place until the 1942–43 season — although even with all the complaints about the current playoff system, this one looks awfully strange from a modern perspective.

The new format basically created a two-tier playoff in which the first-place team from the Canadian Division faced the first-place team in the American Division in a best-of-five series with the winner advancing directly to the Stanley Cup Final. Meanwhile, the second- and third-place teams essentially played their own short tournament to determine the other finalist.

“The change in the rules,” reported the Montreal Gazette on September 24, 1928, “guarantees that at least one of the teams winning the top rung at the end of the scheduled series will be assured of a place in the [finals].” Of course, it also guaranteed that one first-place team would be eliminated! But it was impossible to eliminate them both. And it did create a viable way of keeping all teams active in a six-team playoff format.

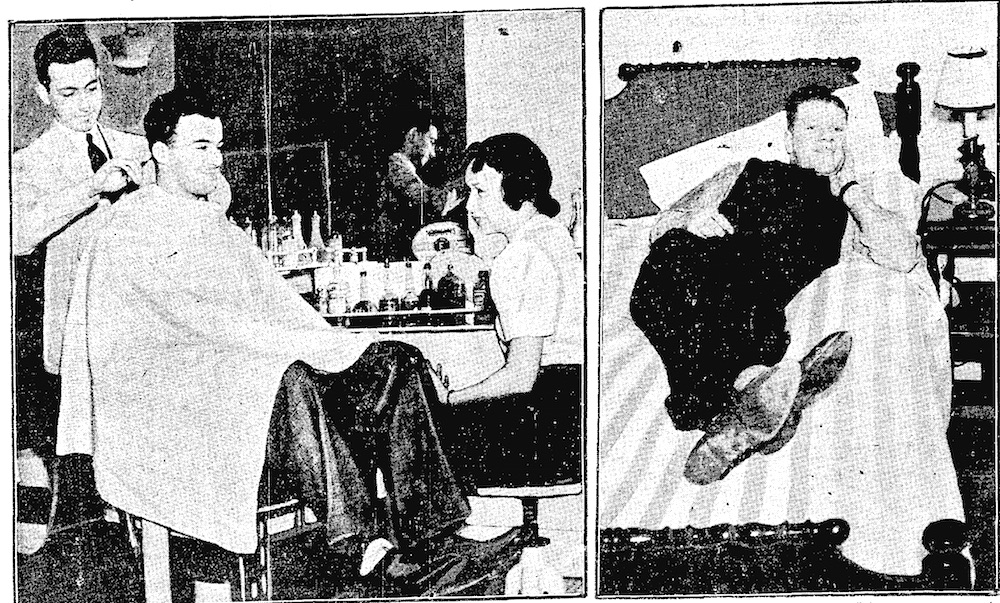

The past is a foreign place! Gordie Drillon gets a haircut and manicure

before scoring the series-winning goal in overtime for the Maple Leafs

over the Bruins in 1938. Turk Broda relaxes in his Boston hotel room.

Another historic note regarding the early ouster of Tampa Bay this year is that it marks the first time in the post-Expansion era that the team that finished first overall in the regular-season standings was eliminated from the playoffs without winning a single game. This has also happened previously, in earlier days of NHL history when series were only two, three or five games long, but it hasn’t happened since 1938. That year, the Toronto Maple Leafs (who’d finished atop the Canadian Division, but only third overall in the NHL standings) swept the first-place Boston Bruins in three straight games.

That 1938 victory over Boston offers something of a cautionary tale to Toronto fans who believe Tampa’s loss and the other upsets clear an easy path to the Finals for the Maple Leafs if they should get past the Bruins tonight. There were upsets aplenty during the 1938 playoffs as well, and a Toronto team that should have easily defeat Chicago for the Stanley Cup lost to what will likely forever be the team with the worst record (14-25-9 in a 48-game season) ever to win it.

But I’m guessing Toronto fans will be happy to take their chances if the Maple Leafs can just beat the Bruins!

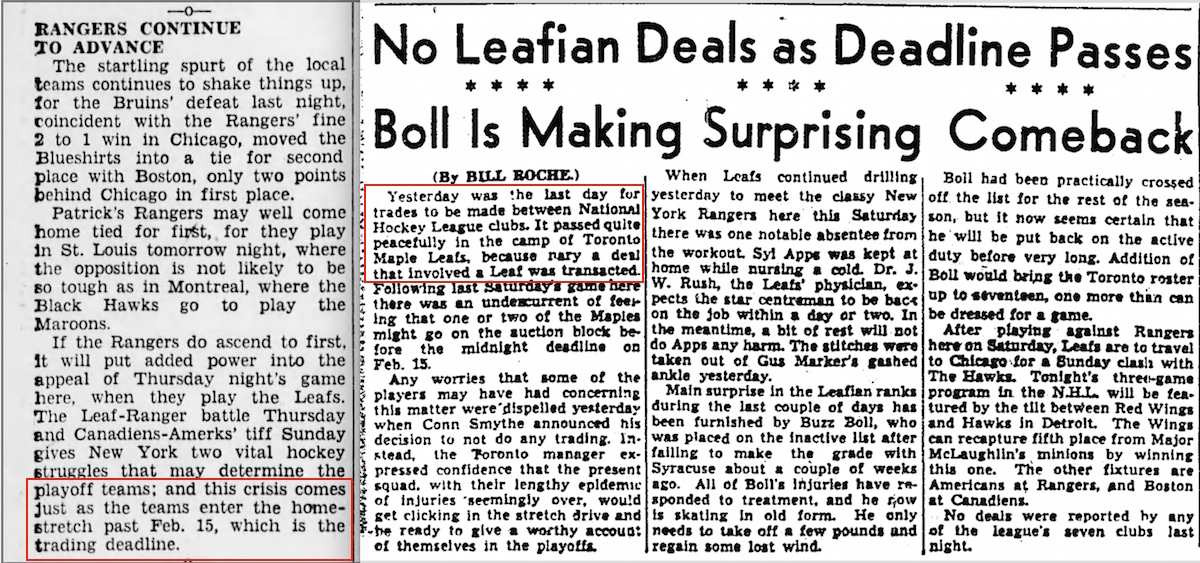

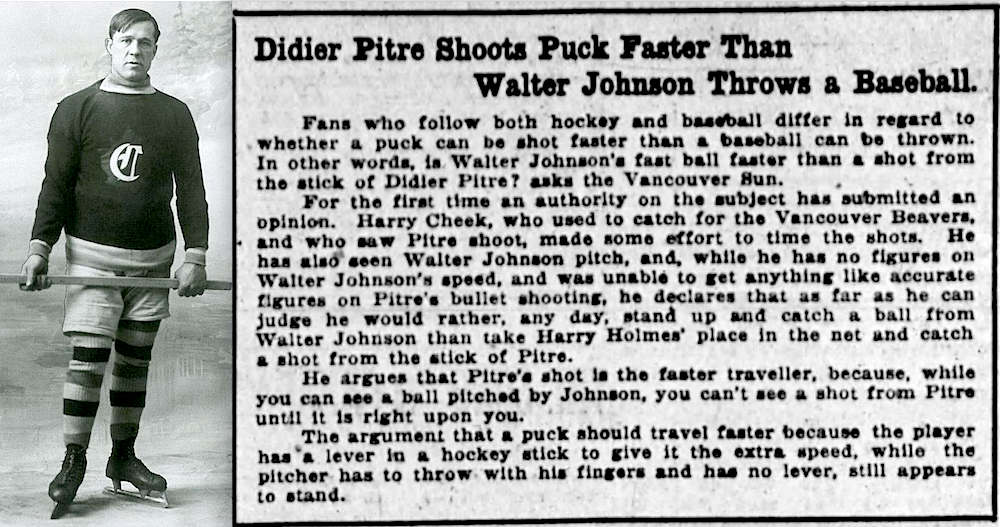

The Ottawa Journal, April 14, 1927.

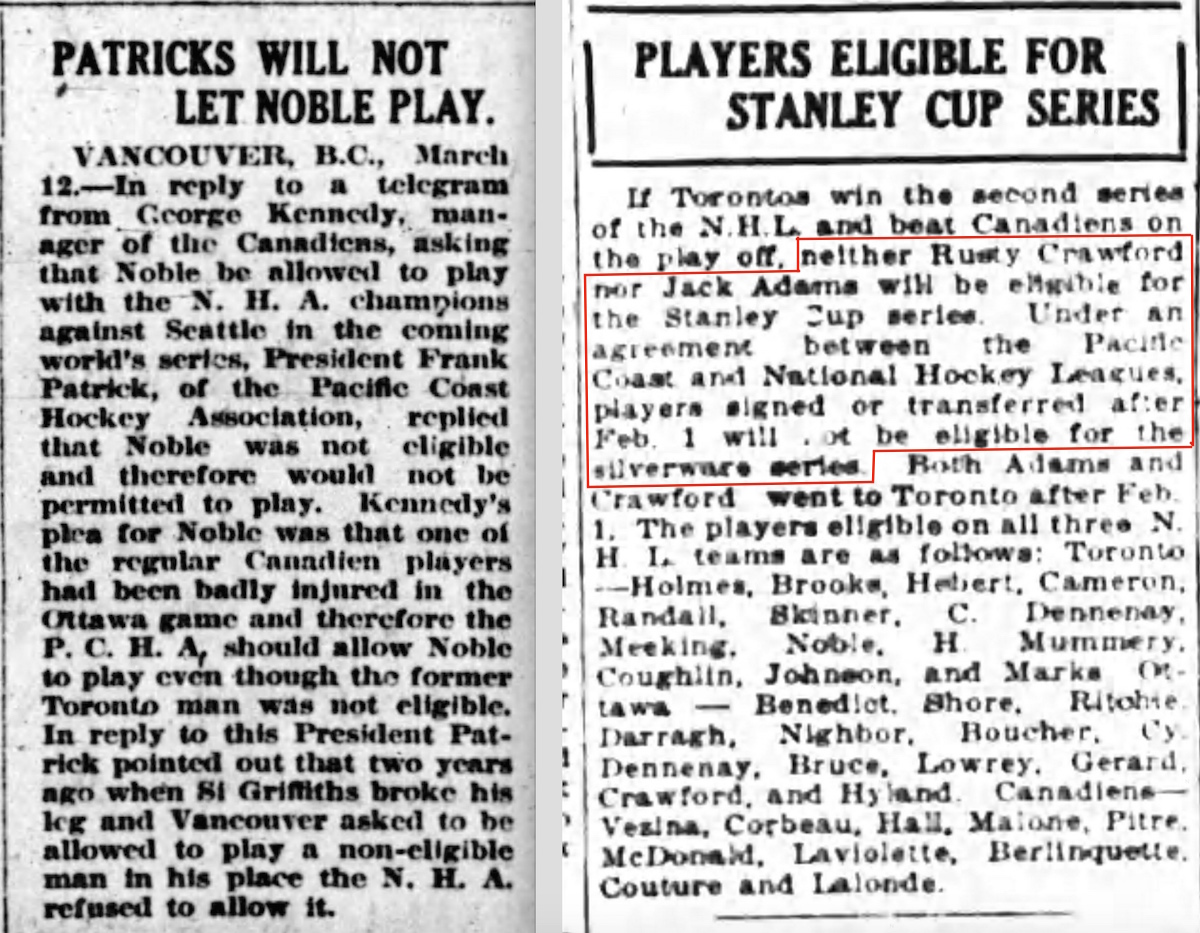

The Ottawa Journal, April 14, 1927. The Ottawa Journal, March 16, 1935.

The Ottawa Journal, March 16, 1935.

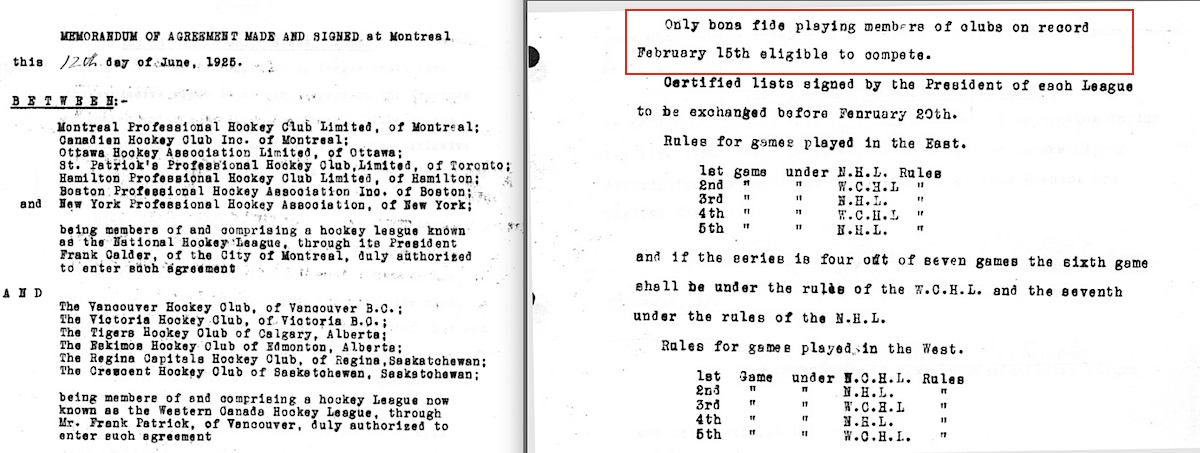

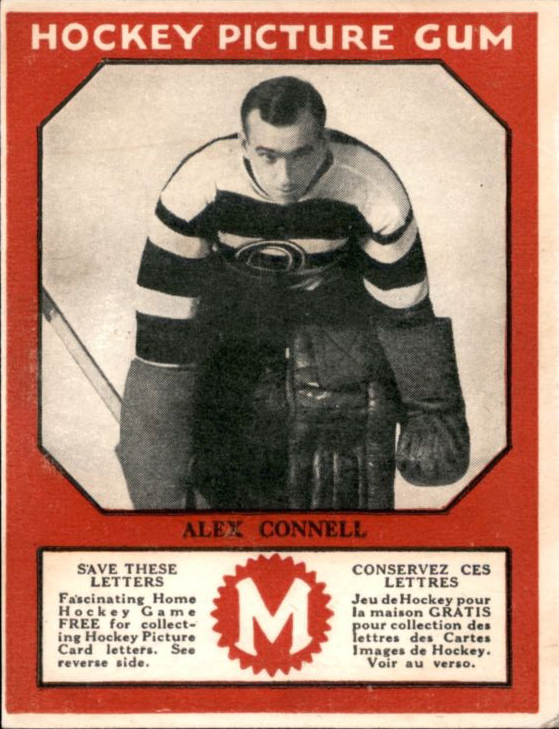

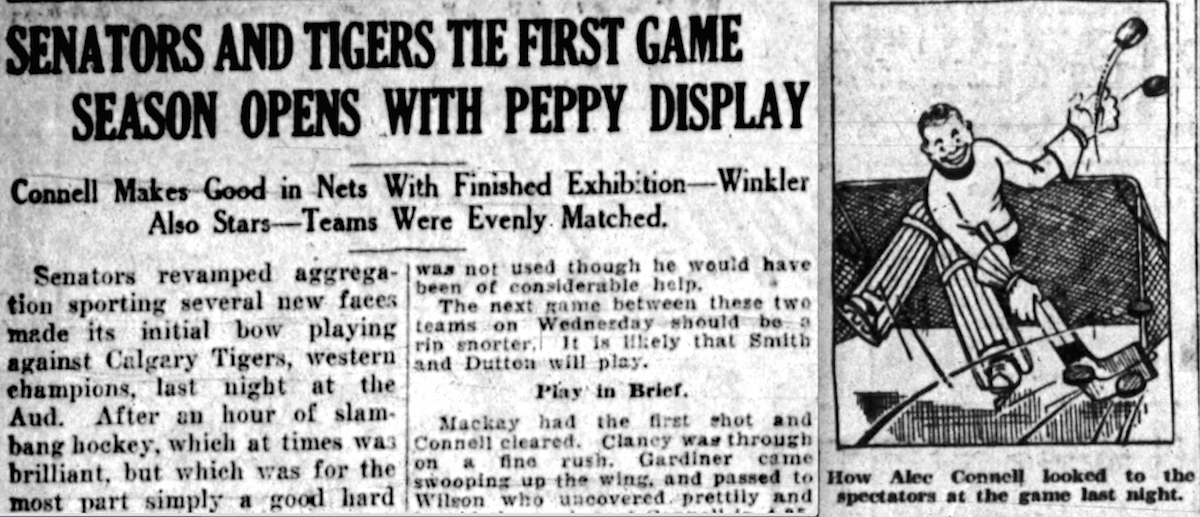

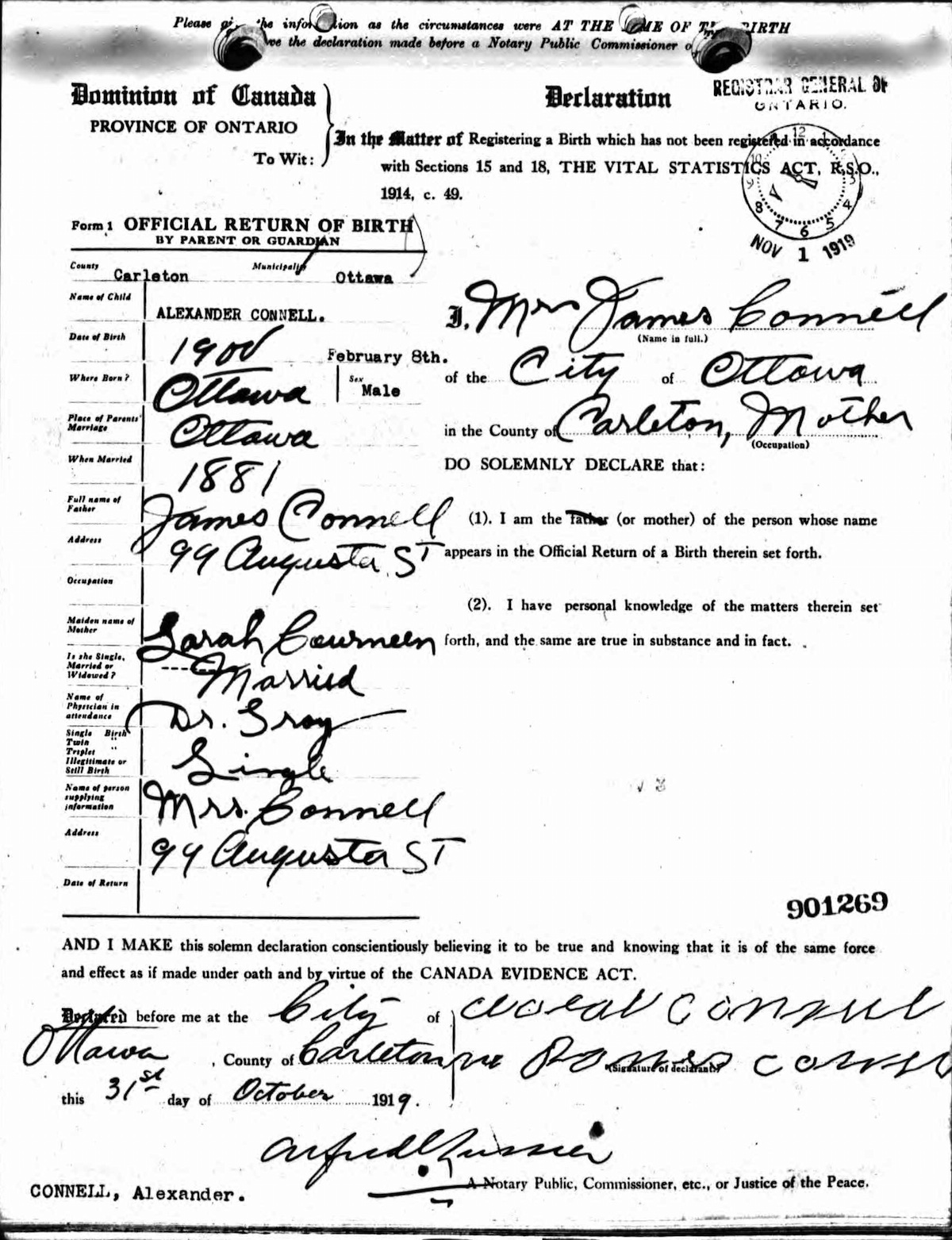

Alec Connell’s debut with the Senators on November 24, 1924 earned a note

Alec Connell’s debut with the Senators on November 24, 1924 earned a note

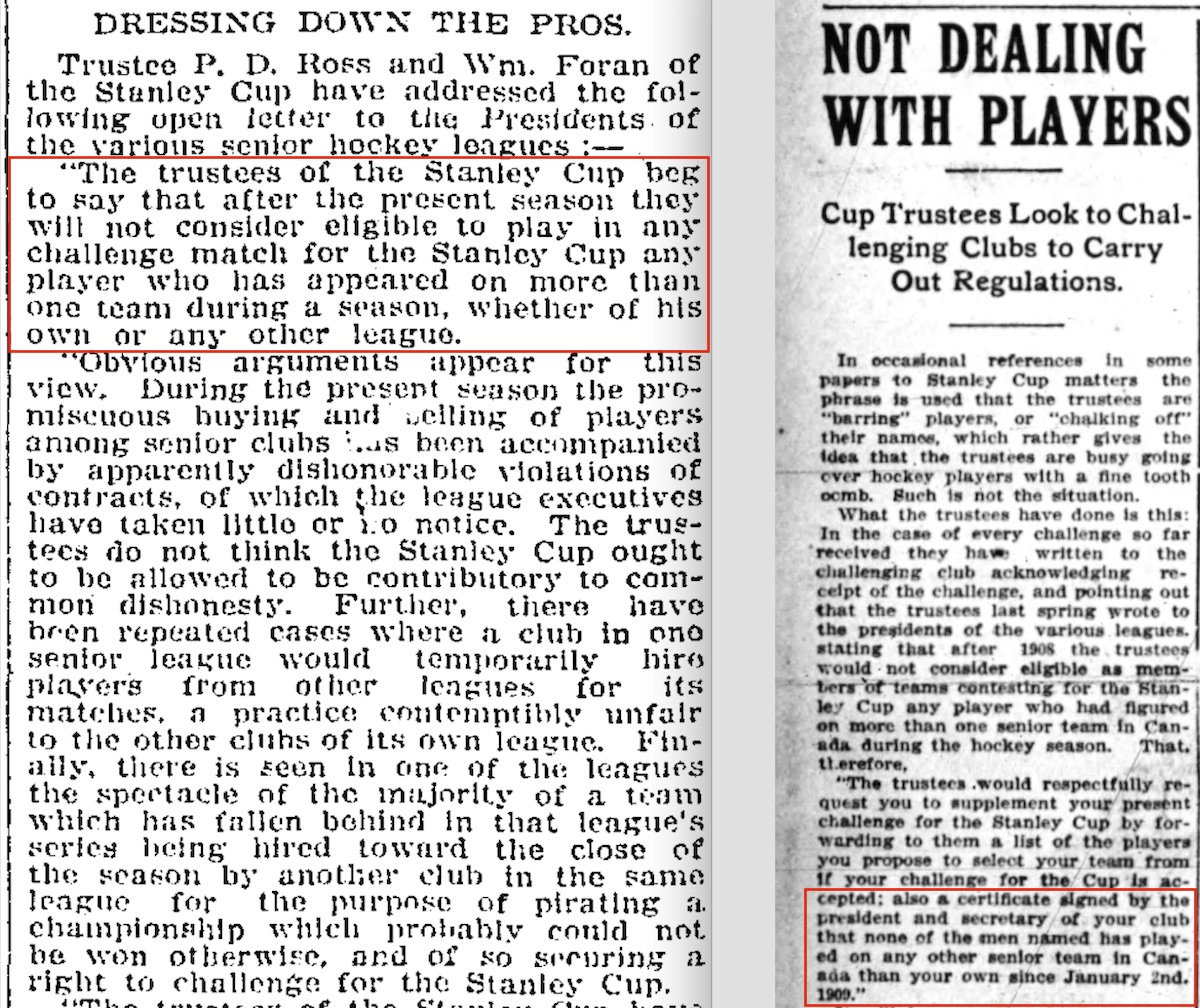

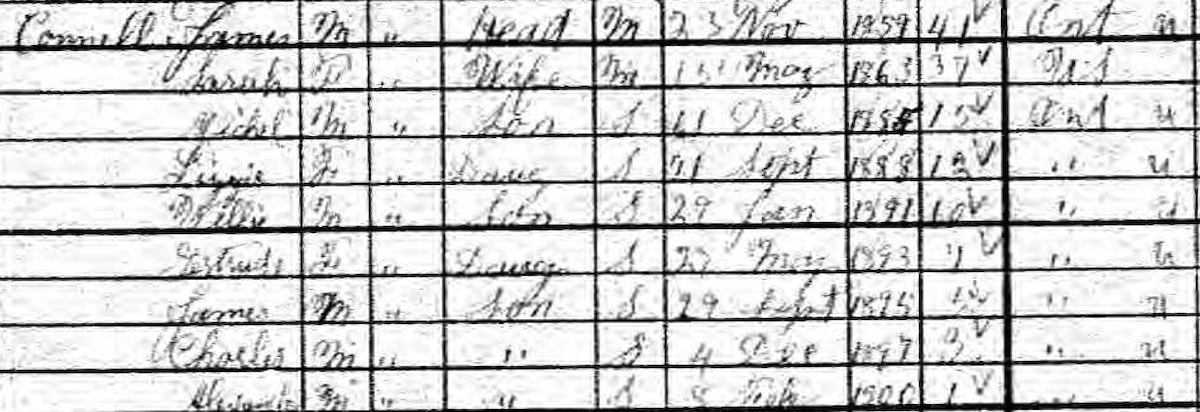

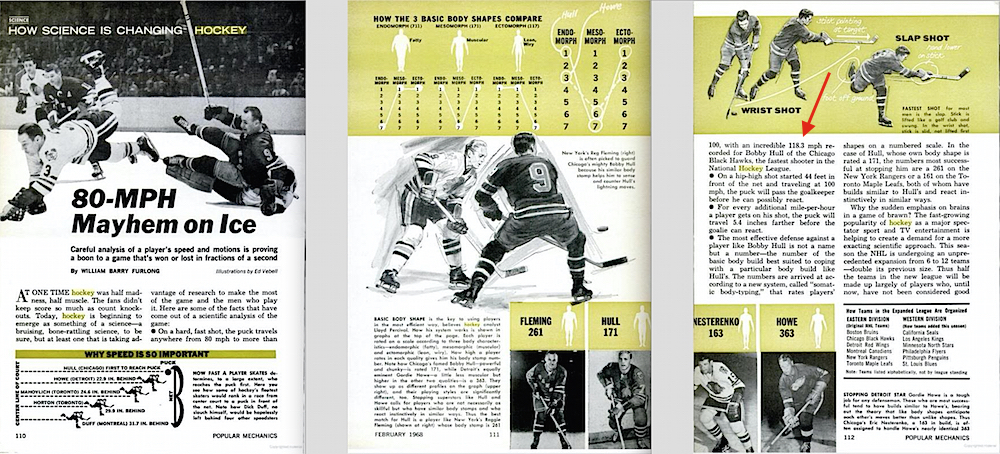

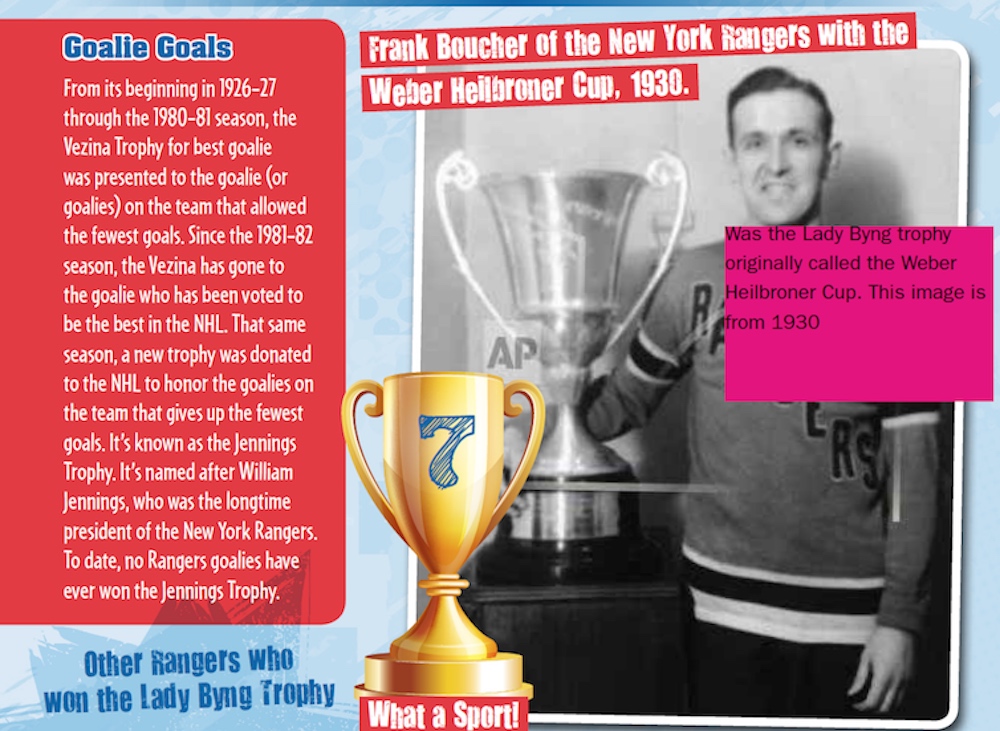

The article on the left is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 24, 1930.

The article on the left is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 24, 1930.