Alex Ovechkin is closing on in 600 goals. He will become just the 20th player in NHL history to reach this milestone … and there’s a case to be made that he might just be the greatest goal-scorer in NHL history. If not the greatest, he’s certainly one of the greatest.

Ovechkin, at age 32, is under contract for three more seasons. Though he’ll have earned $124 million by then under the 13-year deal he signed in 2008, at age 35, he’ll likely choose to stick around for a few more years. Will he be able to score the nearly 300 goals needed to surpass Wayne Gretzky’s career record of 894 goals? Not very likely! But still…

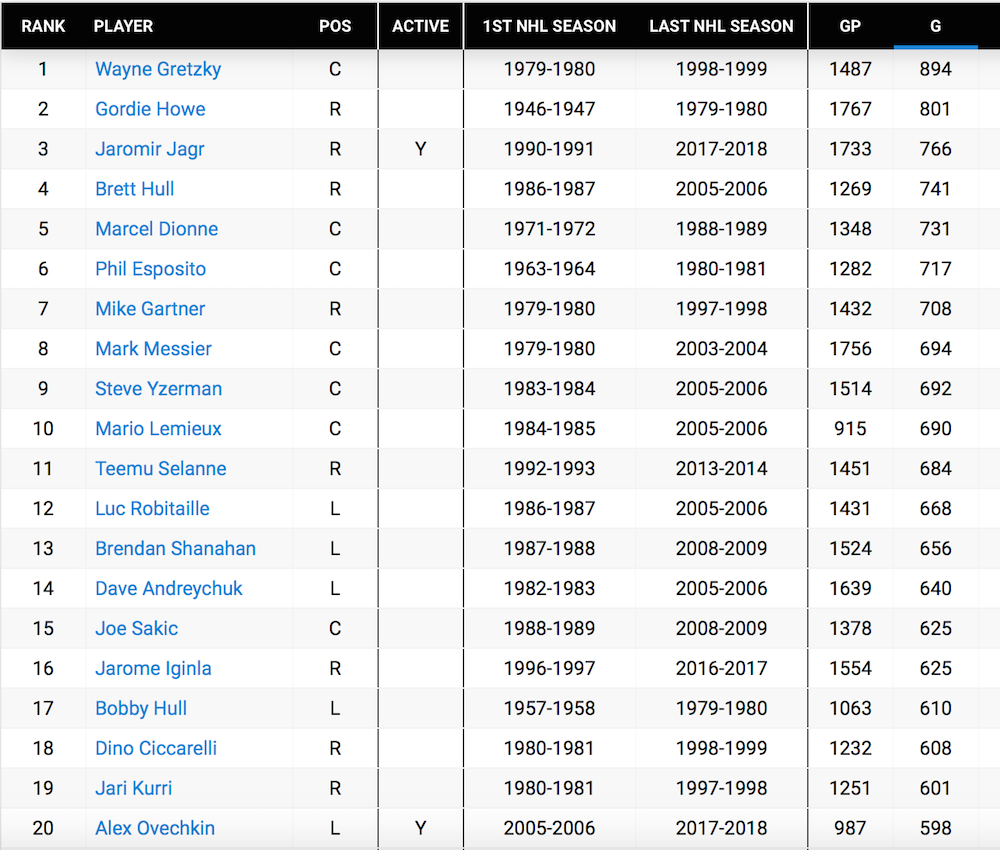

The top 20 scorers in NHL history … through games played yesterday.

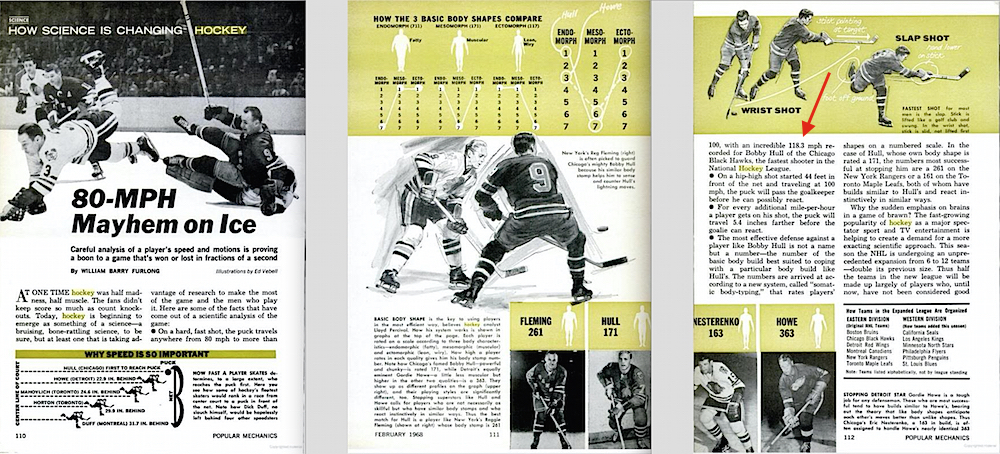

There are a lot more skillful number-crunchers out there than me. I know there are those who can work the numbers to better reflect how relatively “easy” or “hard” it has been to score goals in the NHL in different eras. For me, I rely mainly on what I see. Yes, of course, the game is faster now than its ever been (but hockey has always been as fast as it could be). Still, one need only to look at how few players reach 50 goal or 100 points these days to know that scoring is at a premium in the current NHL.

So here’s the thing about Ovechkin. Virtually everyone who’s above him on the all-time scoring list played the majority of their careers in an era when goals were a lot more plentiful than they are now. The game was a lot more wide open and goalies were not as well-coached or well protected. Of the players ahead of Ovechkin, only Gordie Howe and Bobby Hull played the bulk of their NHL careers at a time when goals were as hard to come by as they’ve been for most of Ovechkin’s career.

In my less-than-scientific approach, I would offer that Ovechkin and Bobby Hull may just be the greatest scorers of all time. And their numbers are remarkably similar. Currently, Ovechkin leads the NHL with 40 goals this seaon. If he holds on (Winnipeg’s Patrik Laine, Pittsburgh’s Evgeni Malkin, and a few others are making it close), this will mark the seventh time that Ovechkin has led the NHL in scoring. That would match Bobby Hull for the most NHL goal-scoring titles. Phil Esposito did it six times, while Wayne Gretzky, Gordie Howe, Maurice Richard and Charlie Conacher did it five times each. Ovechkin also has seven 50-goal seasons, with a shot at eight this year. Only Gretzky and Mike Bossy, with nine each, have more.

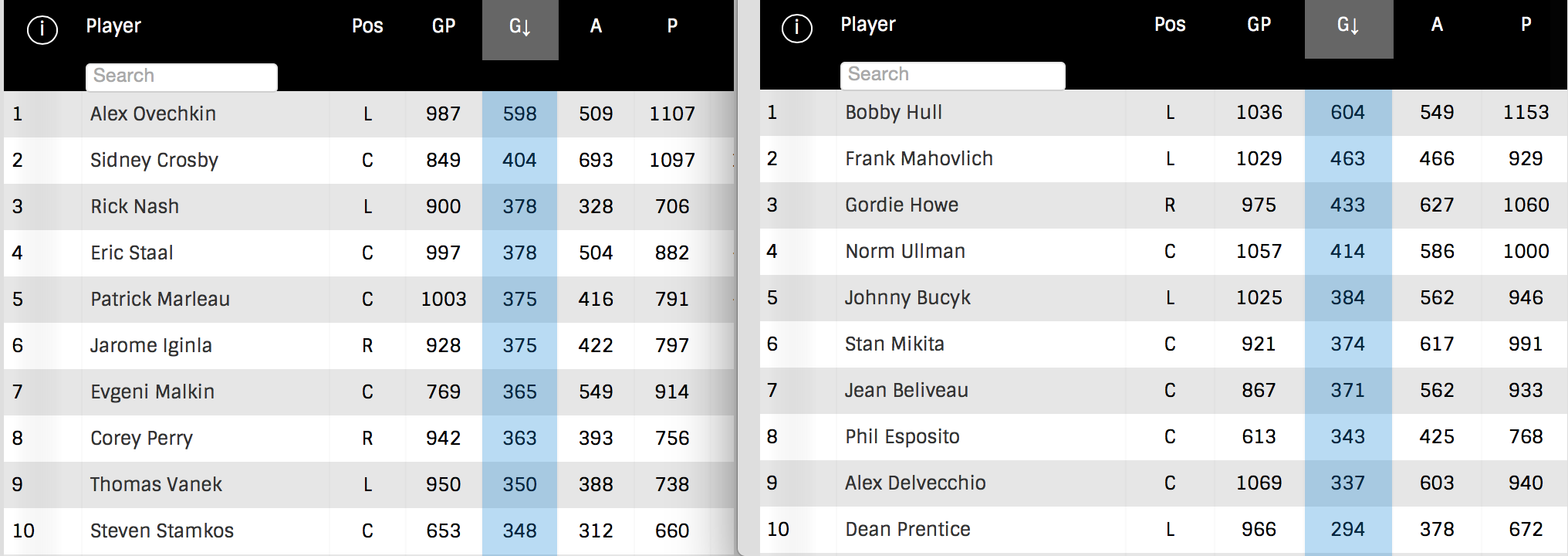

Ovechkin has a huge lead on all other goal-scorers from the time his NHL career began

in 2005–06 through yesterday. The numbers were fairly comparable for Bobby Hull from

the time he entered the NHL in 1957-58 through the 1971-72 season when he reached the

600-goal plateau. (Hull jumped to the WHA after that season.)

When Kelly Hrudy and Ron MacLean discussed this briefly prior to the outdoor game between Ovechkin’s Washington Capitals and the Toronto Maple Leafs in Annapolis last Saturday, they pointed out that at the age of 32, Ovechkin would be the oldest player to lead the NHL in goals since a 33-year-old Phil Esposito in 1974-75. Gordie Howe was also 33 when he led the NHL in 1962-63, as was Maurice Richard in 1954-55. Only 37-year-old Bill Cook, when he scored 28 goals in a 48-game season back in 1932-33, has led the NHL at a more advanced age. (Records have traditionally shown that Cook was “only” 36 … but genealogical sources reveal he was actually born in 1895, not 1896.)

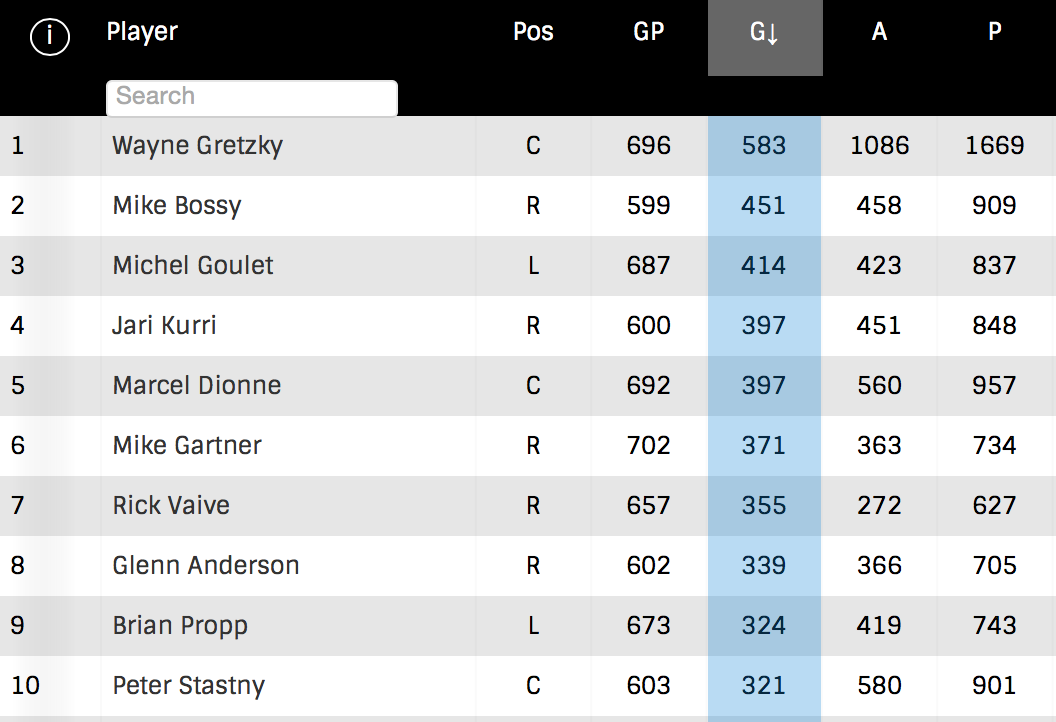

Here’s a look at some of hockey greatest goal-scorers as they were approaching or just passing the 600-goal plateau. These numbers rank the top scorers during the times of the career for each player in question. For example, the statistics for Wayne Gretzky show the goal-scoring totals for players only from the seasons from the start of Gretzky’s career in 1979–80 through 1987-88 when he reached 583 goals. I think these numbers give pretty solid evidence that few players in NHL history have been as far ahead of the rest of the league during their time in the NHL as Ovechkin is today.

Wayne Gretzky scored 583 goals from his first NHL season in 1979-80 through 1987-88.

He had a pretty good lead on all other goal scorers during that period.

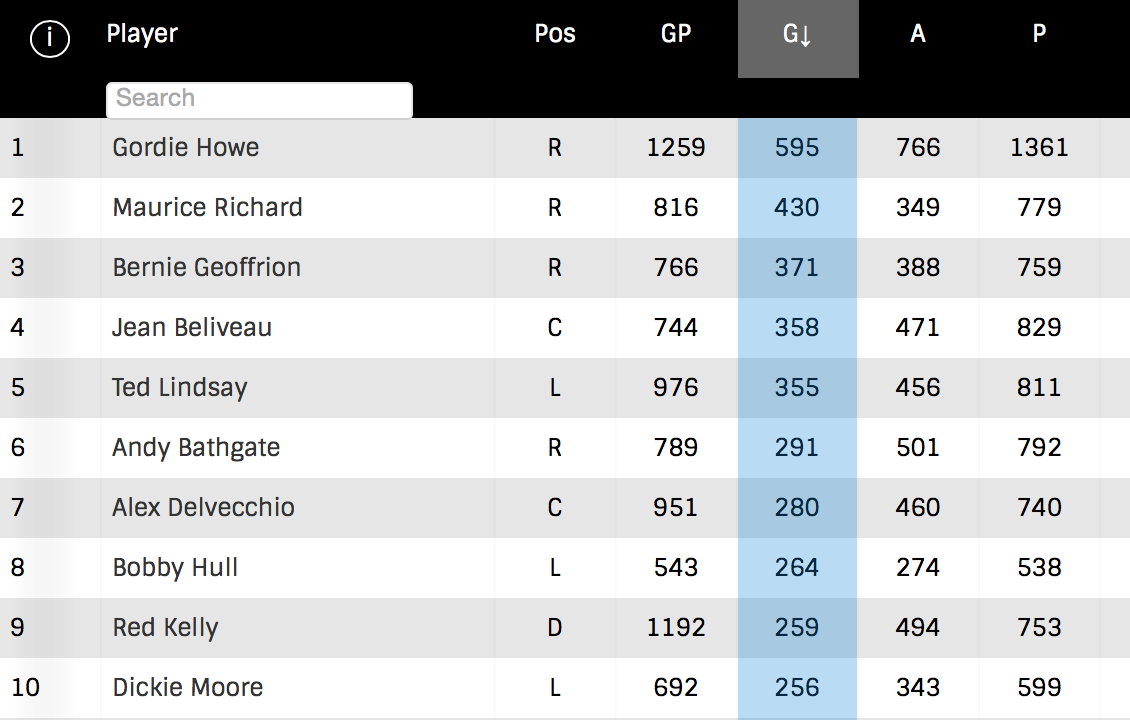

Gordie Howe also had a pretty good lead through 1964-65 on

the players who’d been active since his career began in 1946-47.

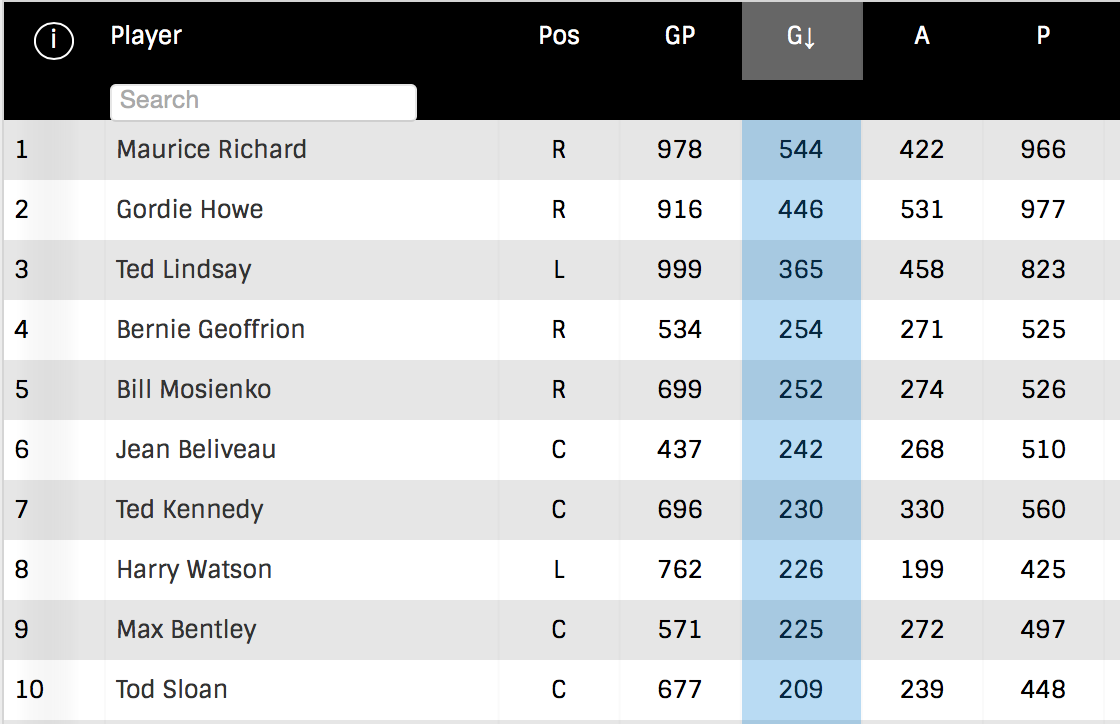

Maurice Richard retired with 544 goals in 1959-60. Only Gordie Howe was close

to him among the players who’d been active since Richard began in 1942-43.

Jaromir Jagr ranks third all-time with 766 goals, but when he topped 600 in 2006-07

there were six others who’d scored over 500 goals since he entered the NHL in 1990-91.

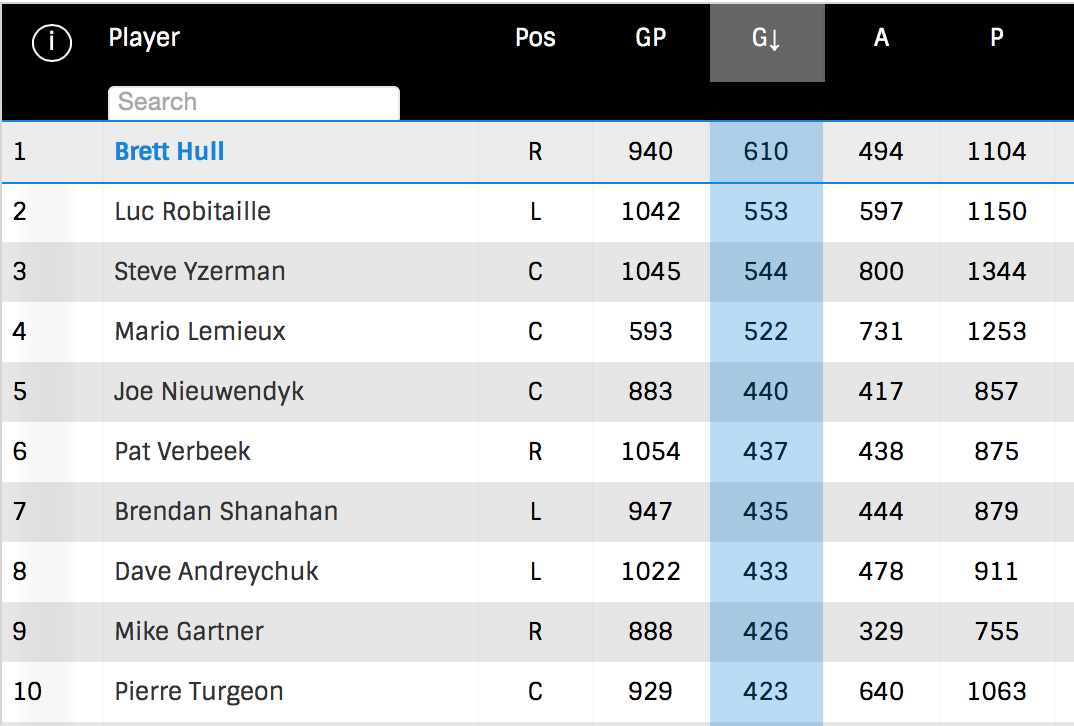

Brett Hull ranks fourth in NHL history with 741 goals. He

scored his first goal in 1986-87 and reached 600 in 1999-2000.

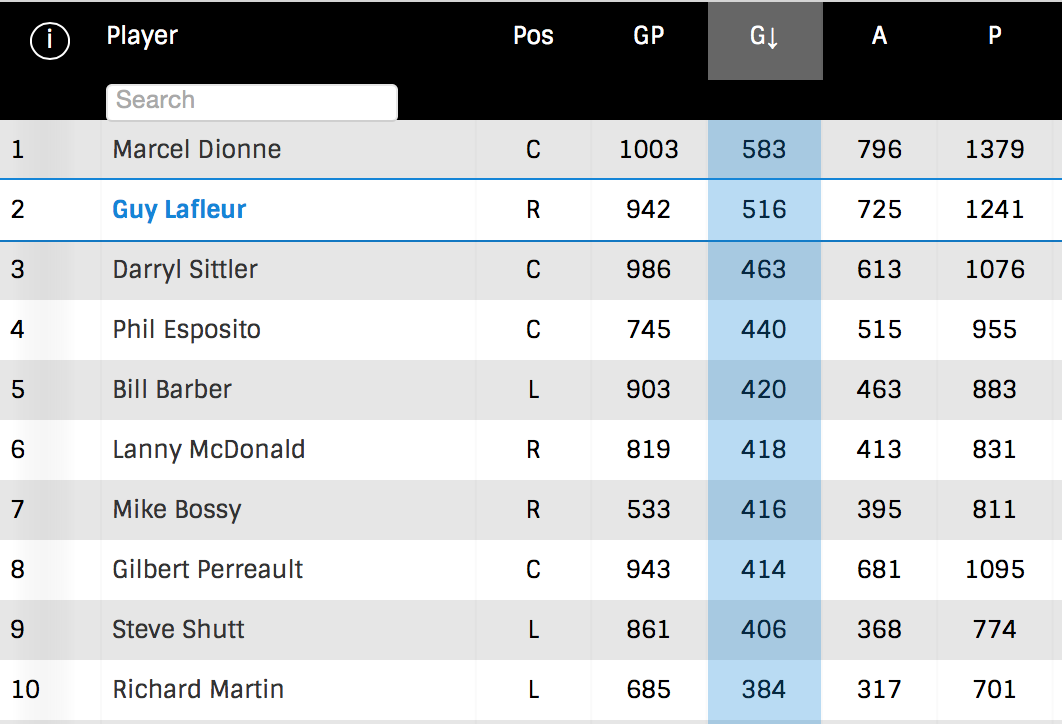

Marcel Dionne entered the NHL in 1971-72 and was approaching 600 goals through 1983-84. Dionne would up his total to 731 over the next five seasons. Guy Lafleur had also been a rookie in 1971-72, but would soon begin a three-year retirement before making a comeback.

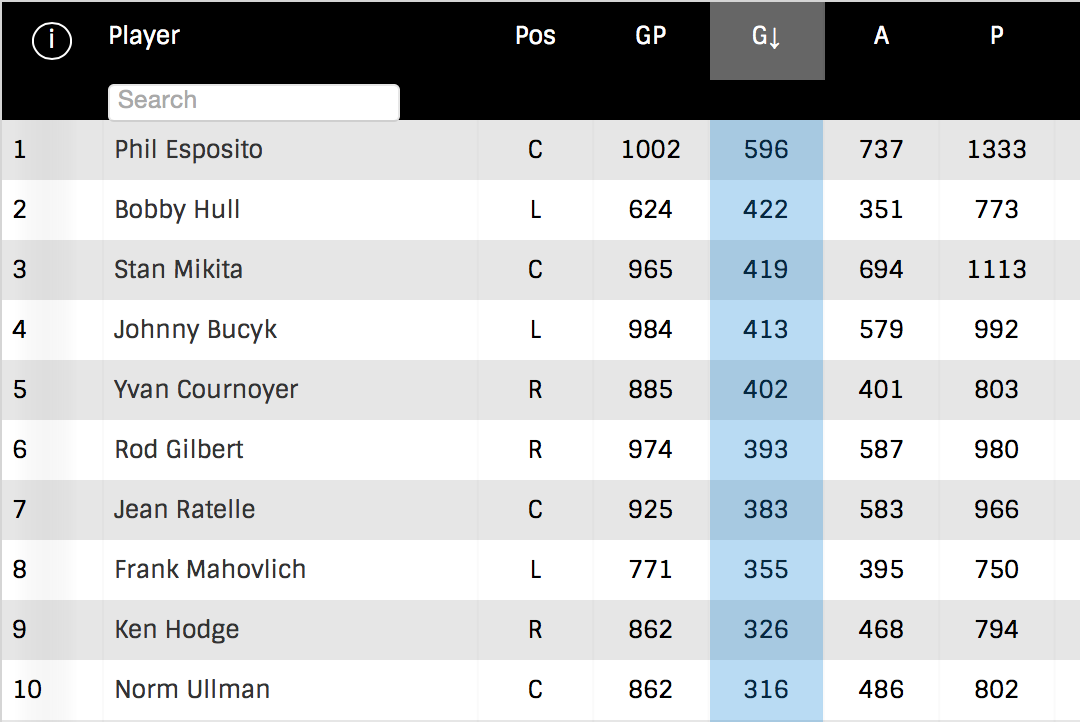

Phil Esposito scored 596 of his 717 career goals goals from 1963-64 through 1976-77

and had a pretty good lead at the time on some pretty big names from those years.

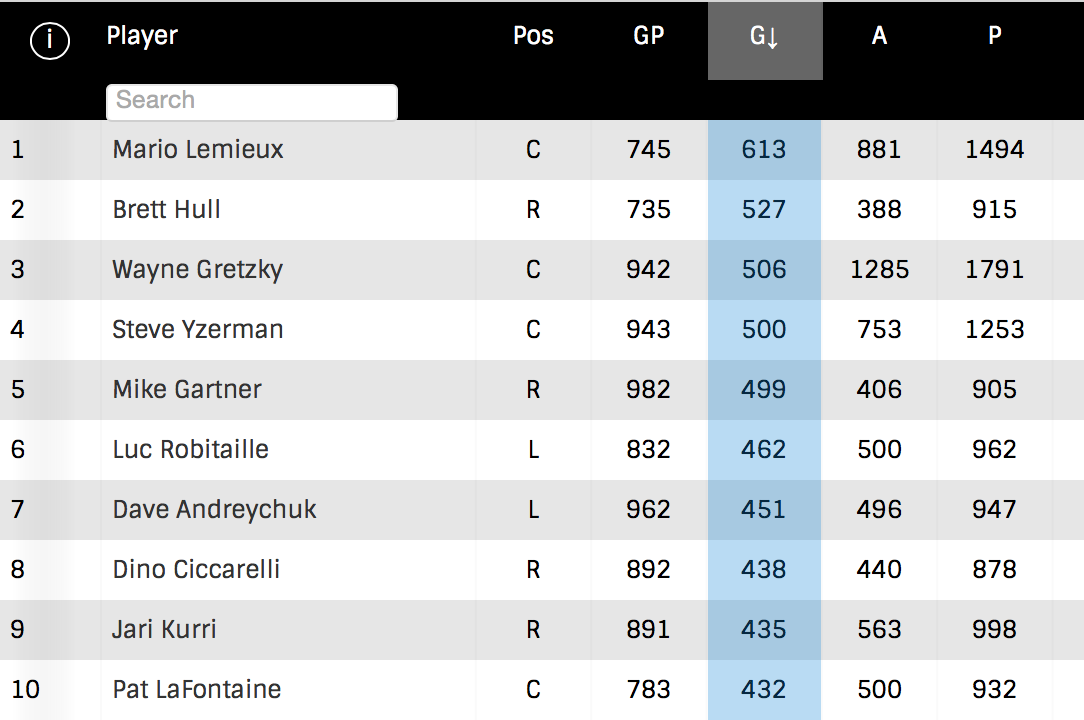

When he retired for the first time after the 1996-97 season, Mario Lemieux had scored

613 goals in just 745 games. Most of the other top scorers from that era had played

150+ more games than Lemieux had since his debut in 1984-85.

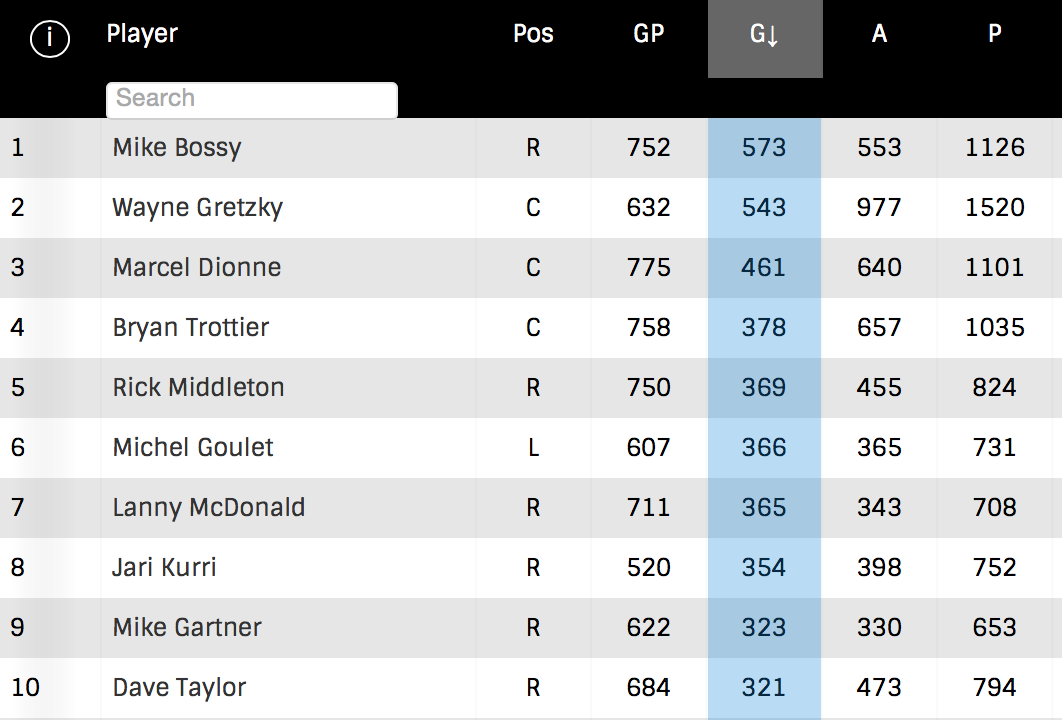

Was Mike Bossy the greatest scorer ever? When injuries forced him to retire in 1986-87,

he’d scored 573 goals in just 10 seasons. His career average of .762 goals per game

is the highest in NHL history among players with 200 goals or more.

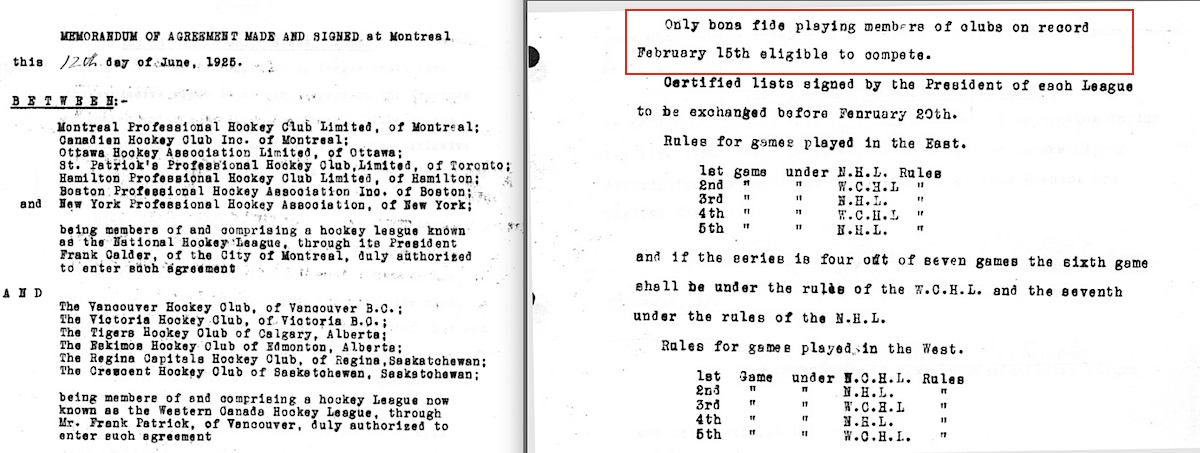

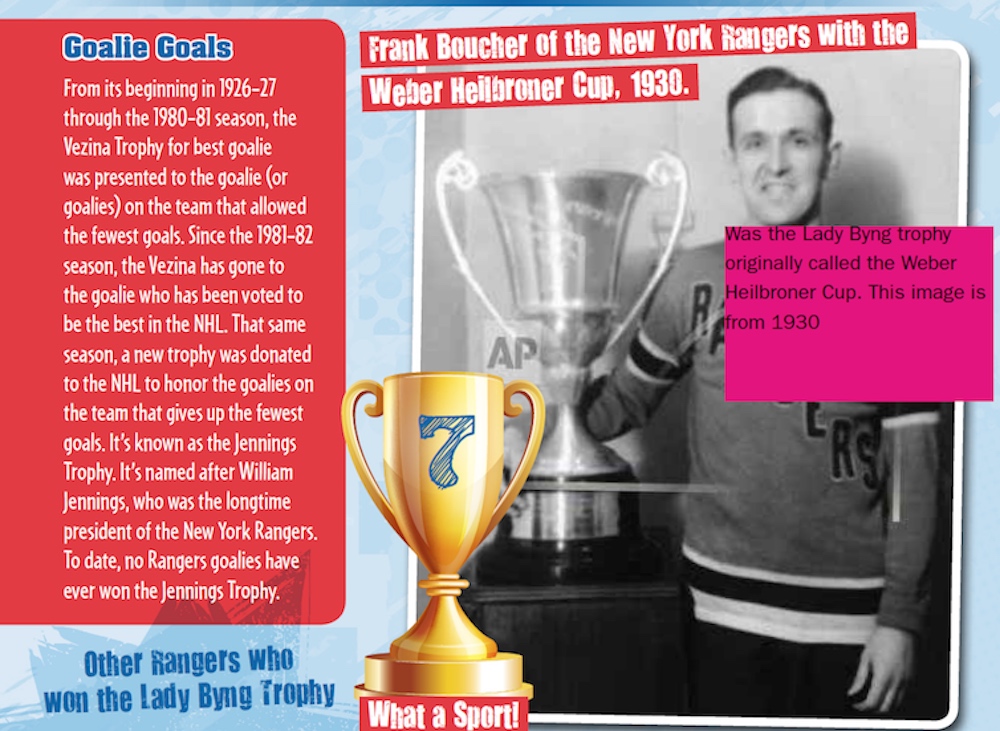

Alec Connell’s debut with the Senators on November 24, 1924 earned a note

Alec Connell’s debut with the Senators on November 24, 1924 earned a note

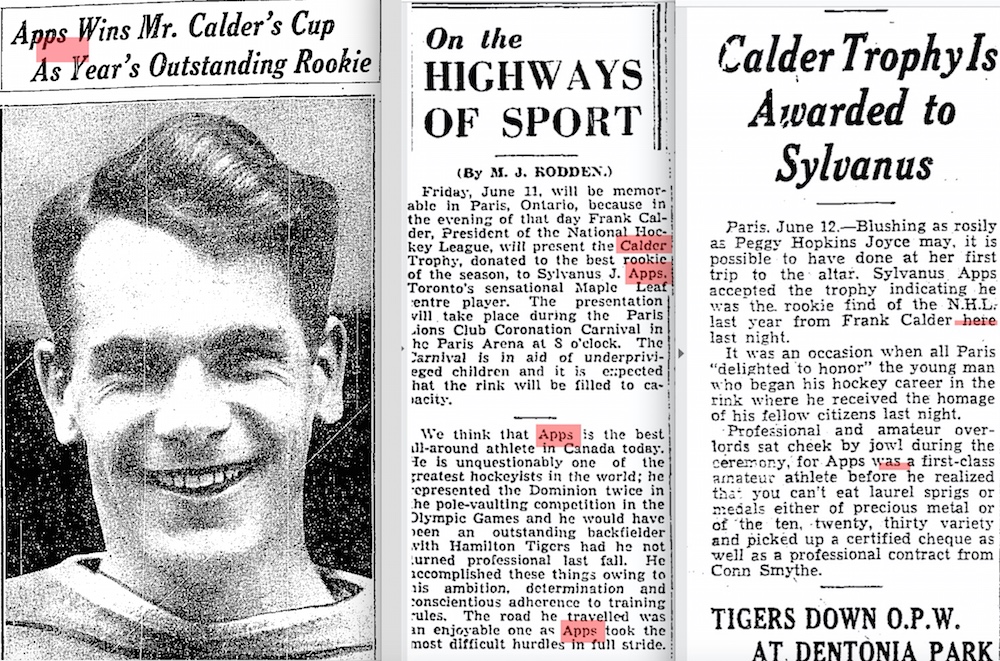

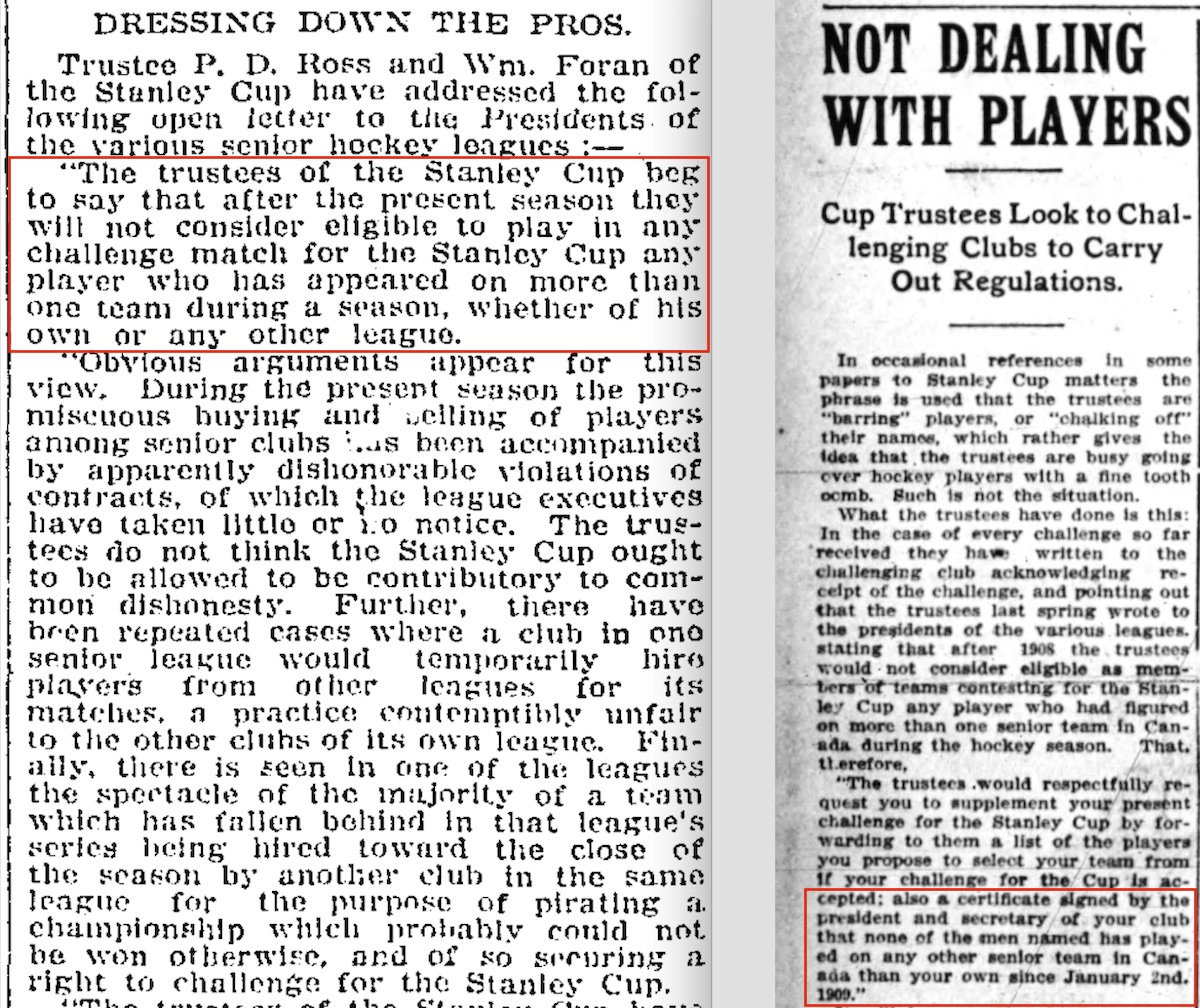

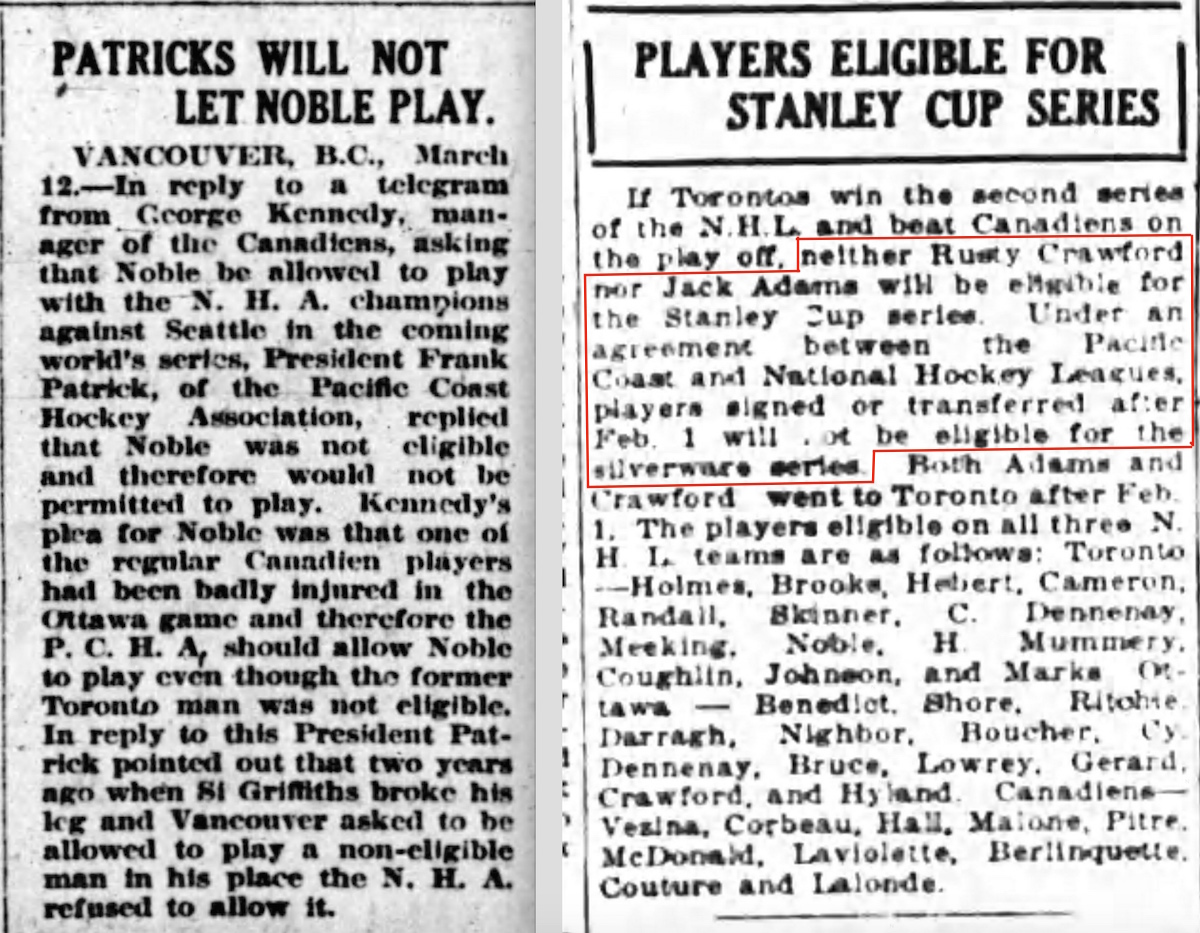

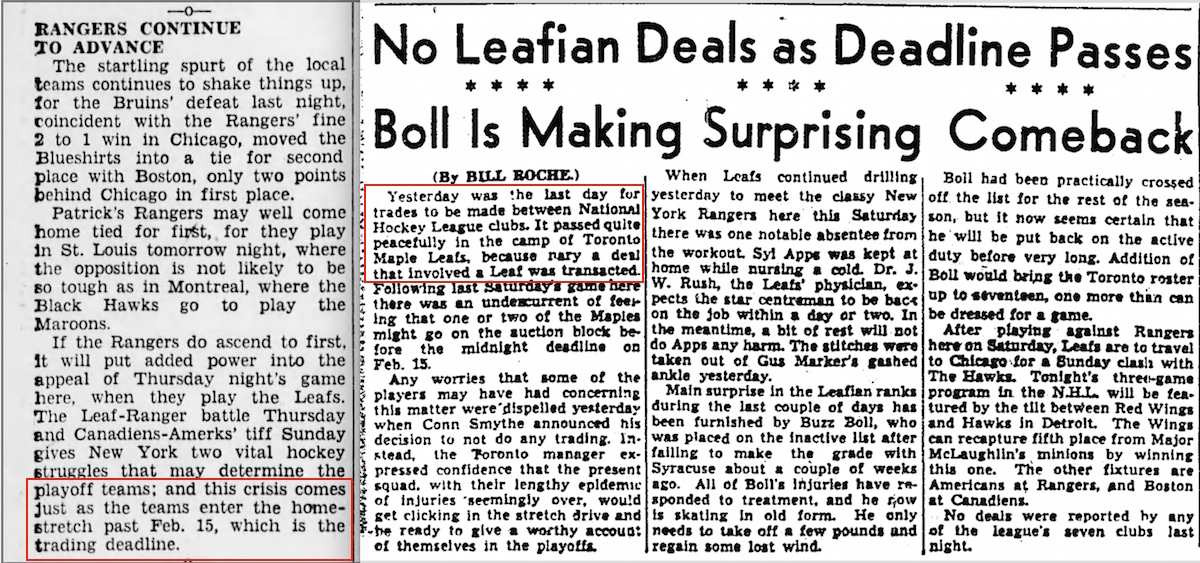

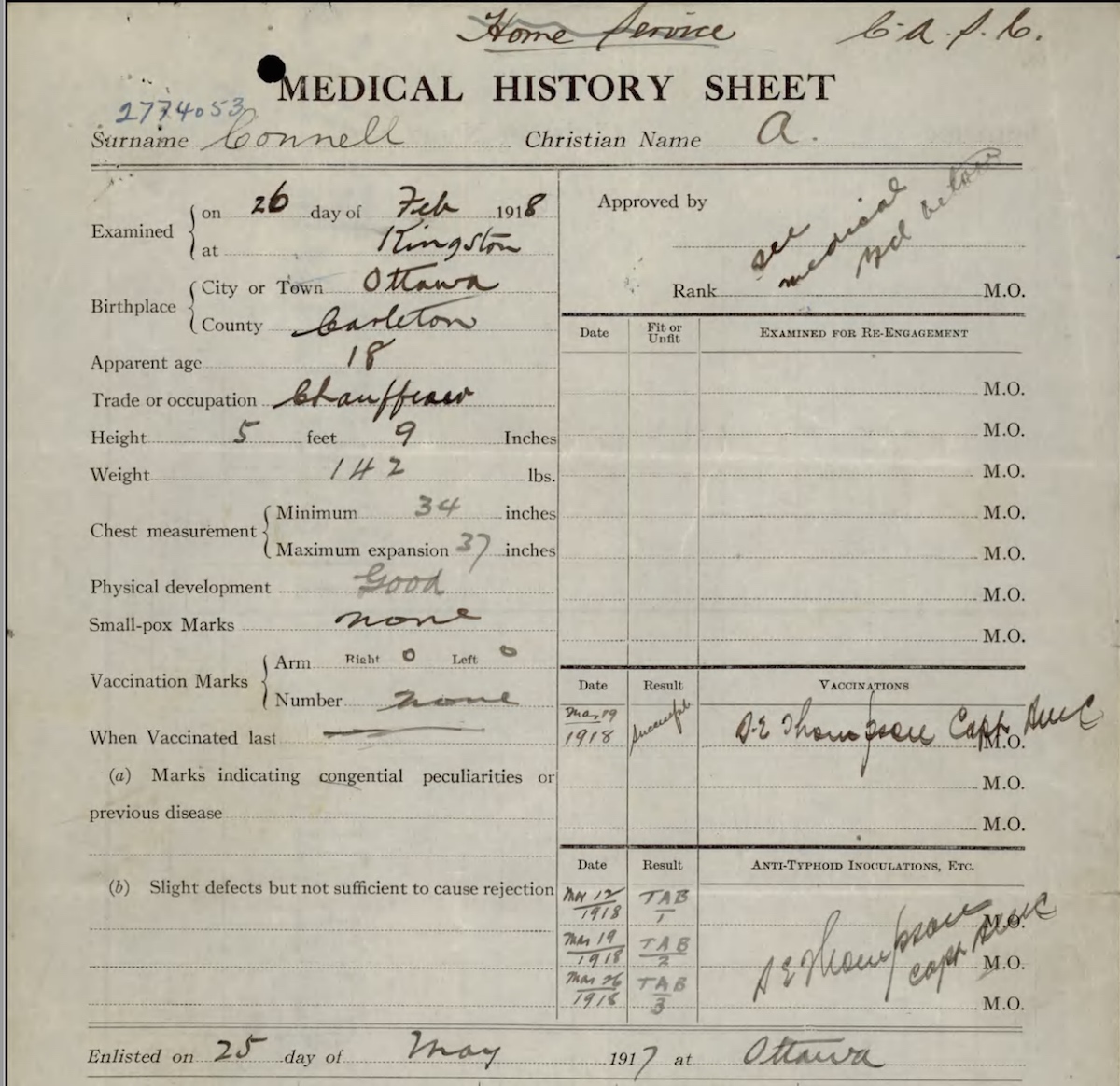

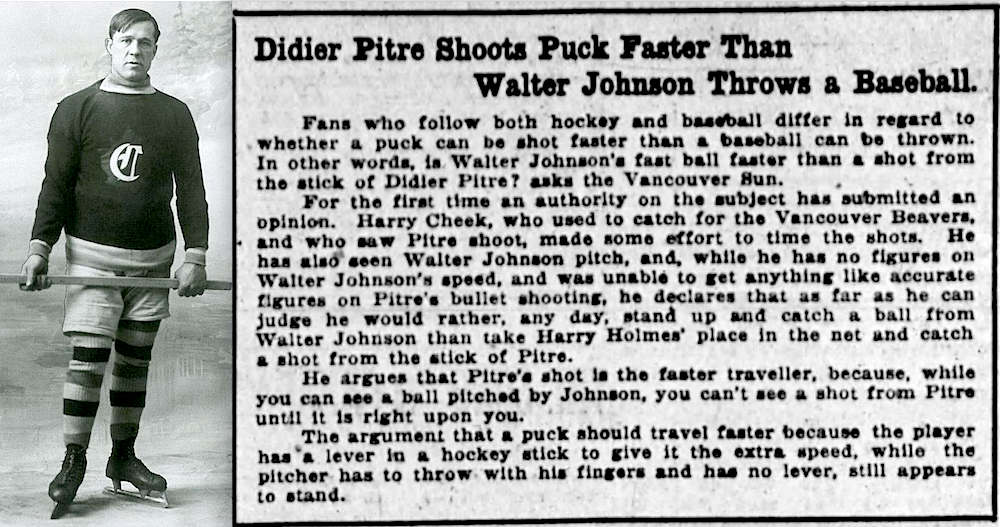

The article on the left is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 24, 1930.

The article on the left is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 24, 1930.