I don’t have a medical opinion. And I don’t usually weigh on on things I don’t know about. Still, I don’t really understand why the NHL seems so gung-ho to get back to business. Intellectually, I understand it. Hockey is big business … and, specifically, they’re not looking to extend any of their current television contracts any further than they have to, which they might be forced to do if they are no playoffs this year. Personally, I couldn’t possibly care less about that reason.

Emotionally, I understand it too. Fans say they want to see hockey back. I care a little bit more about that. Still, I have a hard time taking Gary Bettman at his word when he says “our fans are telling us” they want it. I certainly believe that most fans do want it… I just don’t believe that sways Mr. Bettman as much as he wants us to think. Yes, I seem to recall Bettman saying something along the lines of, “our fans are telling us they want us to get our economic house in order,” during the lockout that wiped out the 2004-05 NHL season. But my guess is, most of those fans would also have said they didn’t want to see the entire season cancelled. (And they DO want NHL players at the Olympics.) So, I basically believe Gary Bettman says and does what’s good for Gary Bettman and the NHL … which is his job, after all.

We have to trust that Bettman is being sincere when he says the NHL won’t come back if it isn’t safe to play … but I wouldn’t want to bet my life on it! I’m not a doctor. I don’t know where we’re headed any better than most of you do. Still, I don’t believe it’s right for thousands upon thousands of tests (or personal safety equipment) to be made available to professional athletes when so many people who truly need them are still going without. It also seems to me that the athletes themselves are being treated by the owners as little more than chattel – well-paid chattel, admittedly – when they’re being told they might have to isolate for months and months to get the season done. But if they agree, then it’s not for me to decide.

Personally, I’d have no problem if the NHL just called off the season and concentrated on restarting anew in the fall if it proves safe to do so. I’ve yet to watch any of the German soccer games without crowds, and I don’t really know what NHL hockey in empty arenas will be like. I’m also not sure I care to be inside watching hockey games in July and August … unless we’re all forced to be inside again by then. And if we are, how safe will it be to play these games?

The one thing on which I do agree with Gary Bettman is that IF conditions prove safe enough for the return of hockey, the proposal the NHL has made to crown a champion seems like an interesting one that should determine a worthy champion.

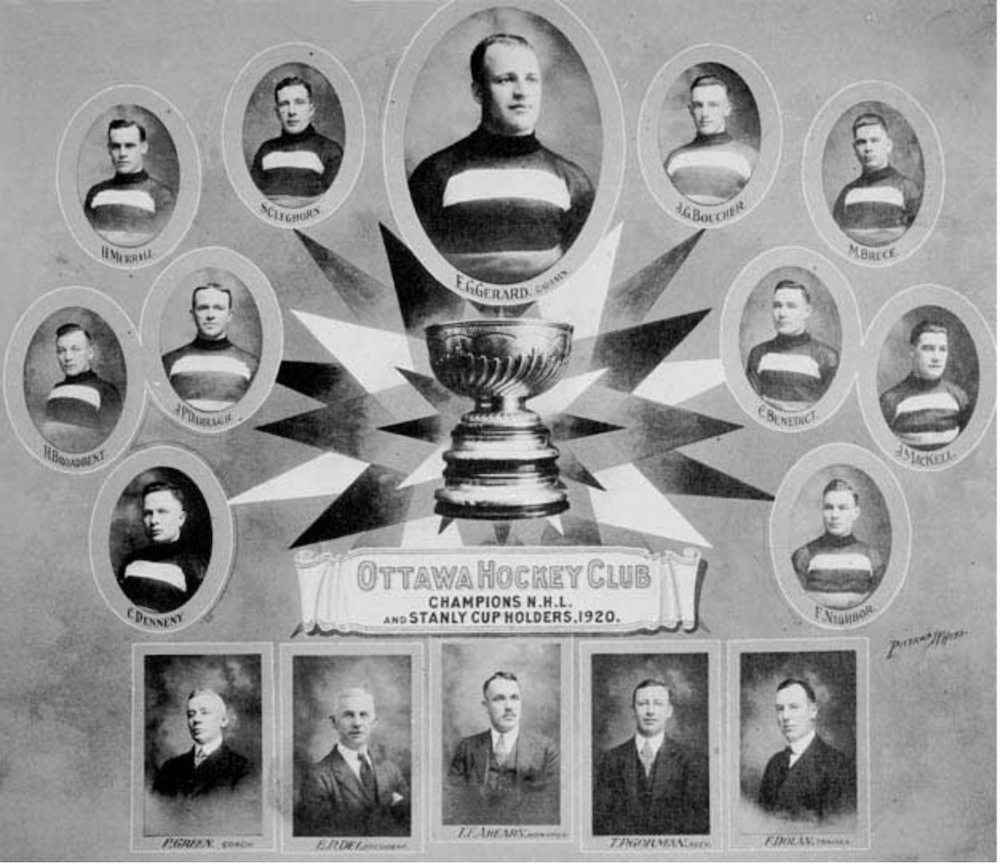

during its long history. So have the Stanley Cup playoffs.

For those who haven’t been paying attention, the NHL has called an end to the regular season. Because no one had completed the schedule yet, and not all teams have played the same number of games, the playoffs that will (might!) commence will be expanded from 16 teams to 24. There will be 12 playoff teams in each of the two conferences. The teams will be housed in two yet-to-be-determined “hub” cities where all the games will take place. The top four teams in each conference based on points percentage from the standings when play was halted will be given a bye through the opening “qualifying round.” While the lower 16 teams are playing in best-of-five series to determine which eight teams will continue in the playoffs, the top teams will play round-robin tournaments to determine their seedings as the top teams in each conference. The playoffs will then proceed with 16 teams playing four rounds to decide the Stanley Cup champion. It isn’t known yet if all the playoff rounds will be best-of-sevens as we’ve become used to, or if the first two rounds might be something shorter.

A while back, I heard several NHL players on TV saying how the only true and fair way to determine the Stanley Cup champion is through four rounds of best-of-seven playoffs. I’ve read writers who’ve commented that with anything less, “historians will call the championship into question.” Well, this is one historian who will never call it into question!

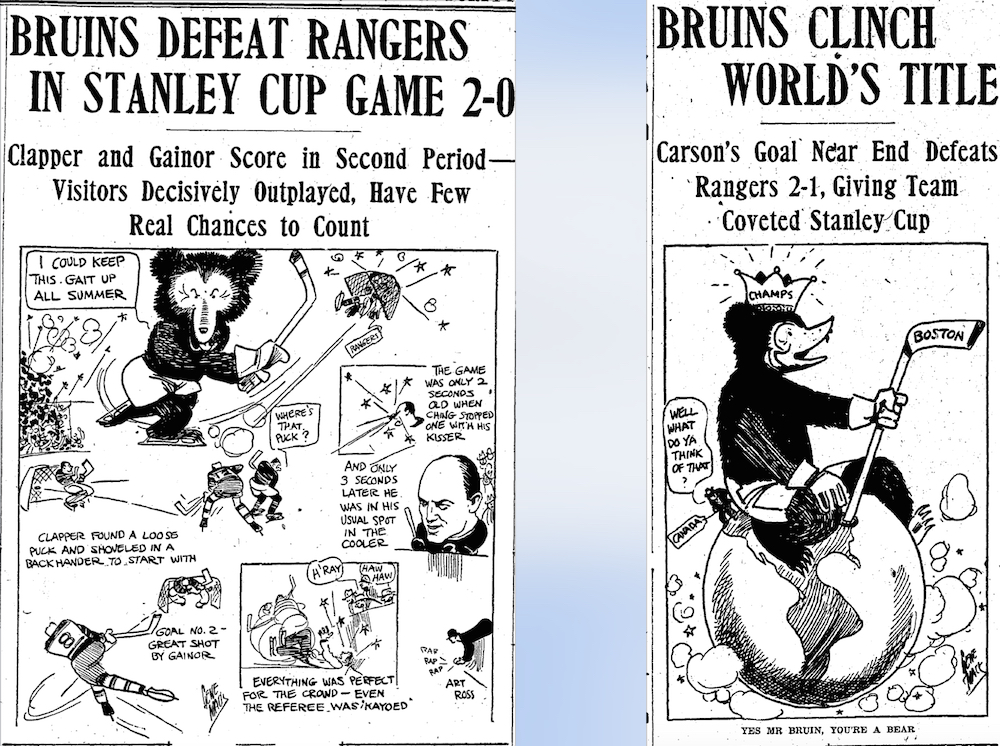

The NHL likes to boast that the Stanley Cup is the hardest championship of all to win. That may be true, but the NHL playoff format has hardly been carved in stone! Yes, the NHL has been playing four rounds of playoffs since 1980, and all four rounds have been best of sevens since 1987. Yet even within that setup, the NHL has tinkered plenty. And before that? Does anyone question the greatness of the 1970s Montreal dynasty because they didn’t have to win 16 playoff games? (Only 12.) Or any of the great teams of the so-called “Original Six” era because they had to win just two rounds of playoffs? Hell, even the great Islanders teams of the early 1980s, who won an astounding 19 straight playoffs series, only had to win 15 games, not 16.

And even if it’s true that the NHL is mainly trying to salvage the playoffs for financial reasons, it’s also true that the playoffs in professional hockey have almost always been about the money!

In the early days of hockey, there were no playoffs at all. League champions were simply the team that finished the schedule with the best record. Postseason games were only played to break ties if two teams topped the standings with identical records. Once the Stanley Cup came along in 1893, championship teams from rival leagues were allowed to challenge the reigning champion for the trophy. There were still no league playoffs, and some of these teams played as few as four regular-season games. None in these early years played more than 20. Before 1914, the Stanley Cup challenges these teams took part in were either a one-game, winner-take-all match, a two-game, total-goals series, or a best-of-three playoff.

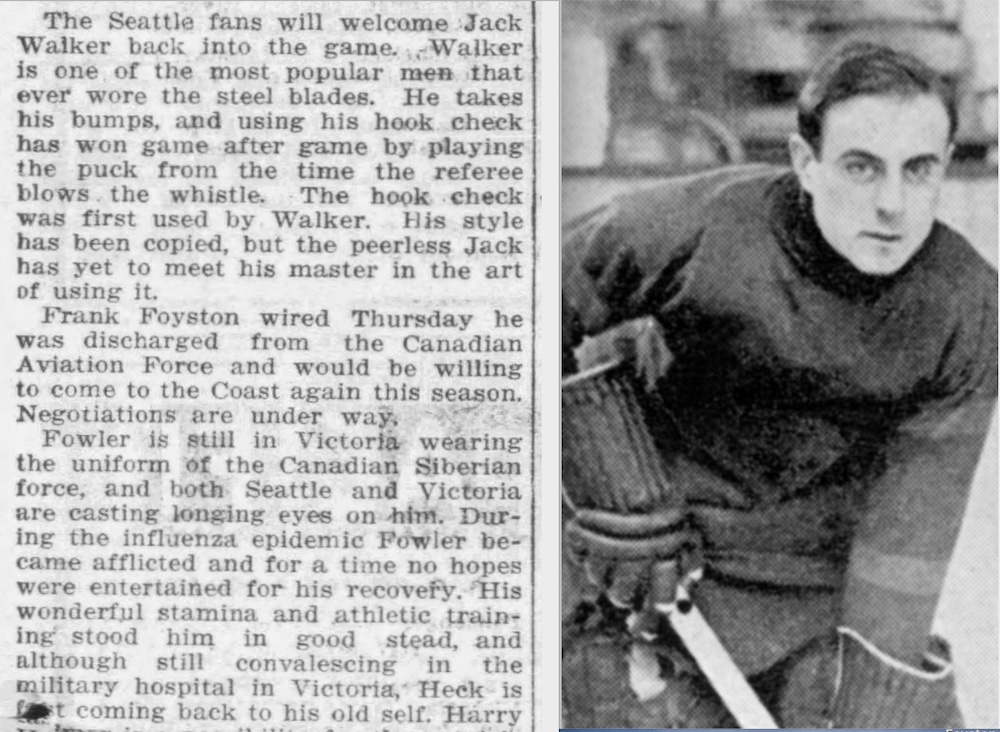

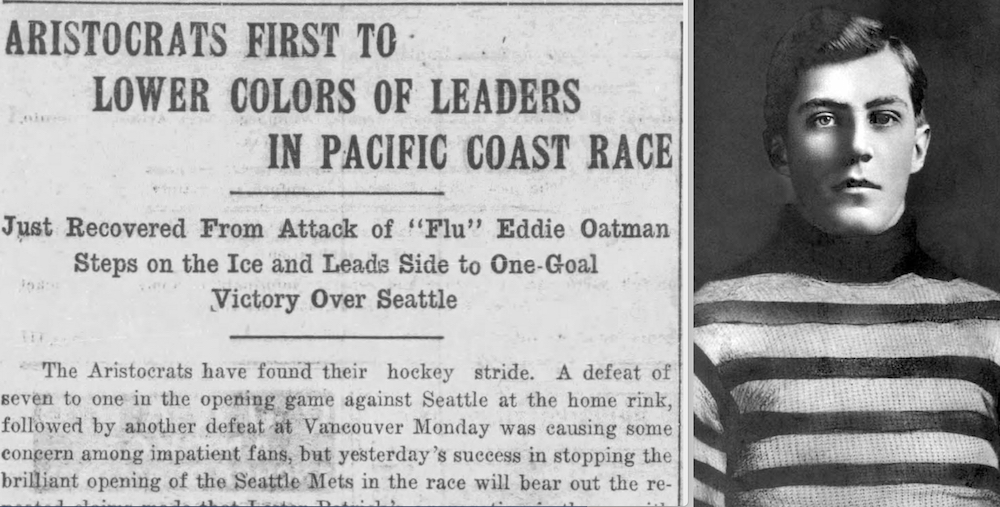

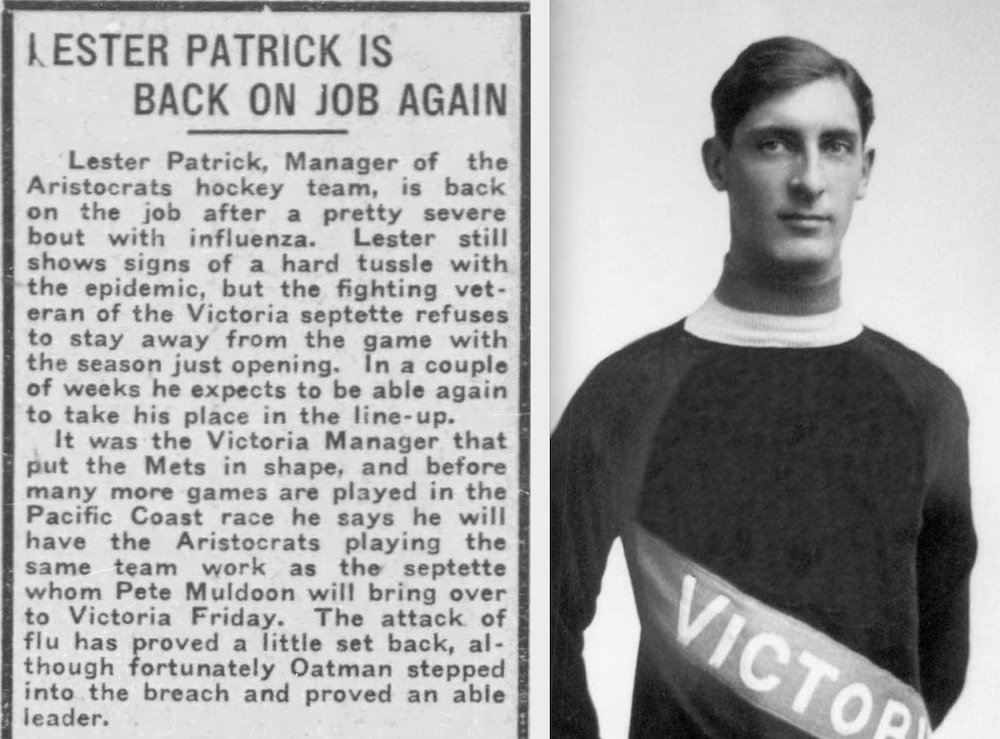

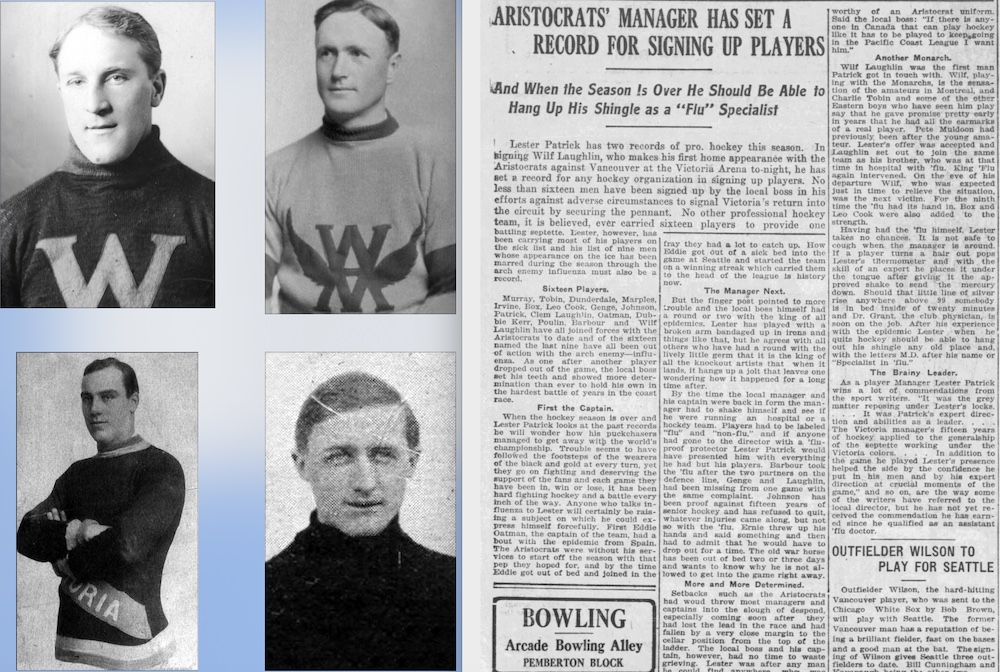

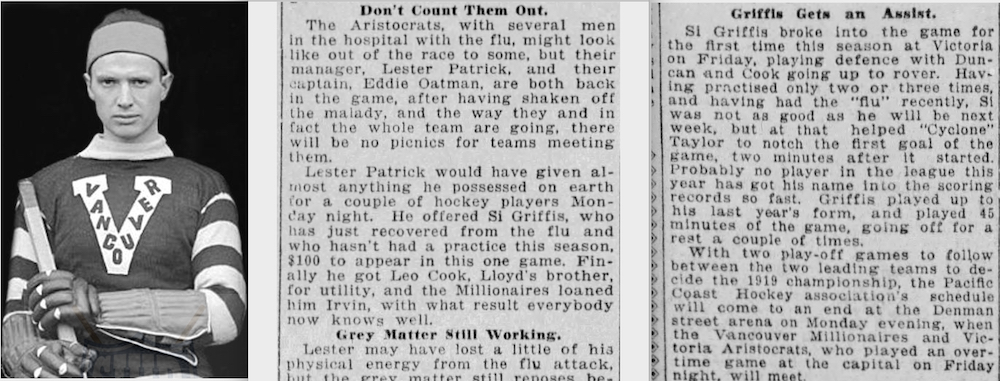

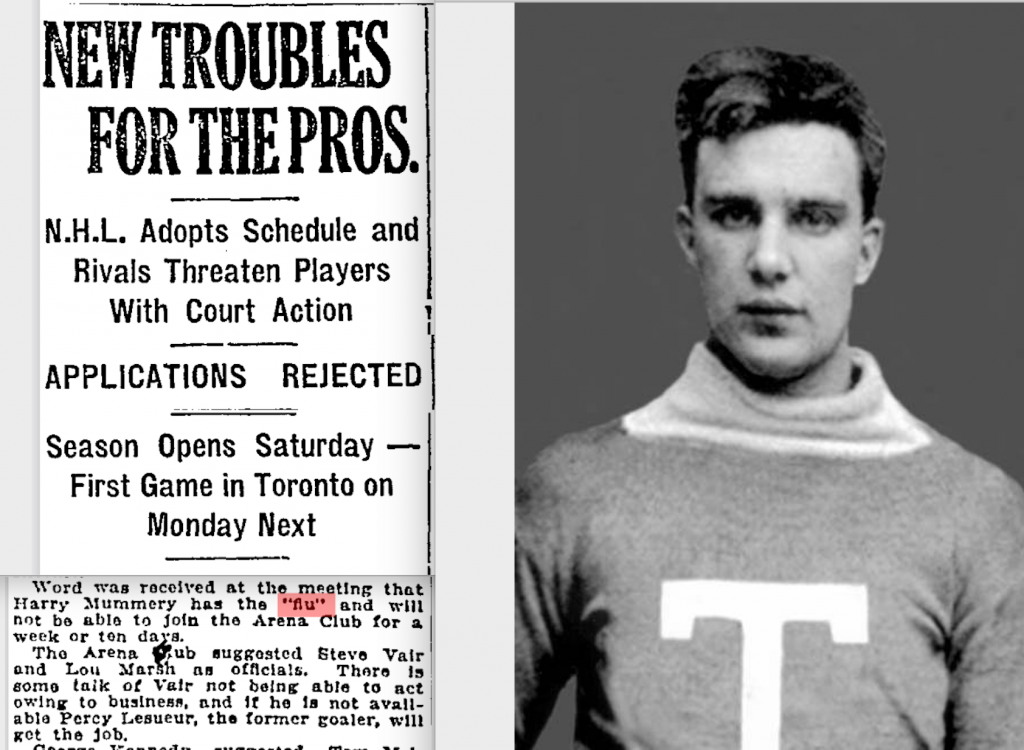

These limited Stanley Cup formats were first called into question before the start of the 1912-13 season. Lester Patrick and his brother Frank had created the Pacific Coast Hockey Association the year before. In October of 1912 (likely influenced by the Boston Red Sox thrilling World Series win over the New York Giants), Lester Patrick spoke of his desire to see the Stanley Cup playoffs enlarged to a best-of-seven series, or even a best-five-of-nine. When Lester’s 1912–13 Victoria Aristocrats won the PCHA championship, he would have liked to challenge the National Hockey Association’s Quebec Bulldogs for the Stanley Cup. However, he realized that he wouldn’t even be able to cover his expenses if he took his team some 3,000 miles across Canada by train to play a two-game series in Quebec’s tiny home arena. The following season, the PCHA and the NHA agreed that their two champions would meet in an annual best-of-five Stanley Cup series. The NHL would continue that agreement, and a best-of-five mostly remained the Stanley Cup standard (with a couple of best-of-threes on occasion) until the first best-of-seven Final in 1939.

As for league playoffs en route to the Stanley Cup, the first time a top hockey league created its own independent playoff was in 1916-17 when the NHA split its regular season into two parts. The champions from the first half of the schedule met the champions from the second in a postseason playoff for the right to take on the PCHA champions for the Stanley Cup. (The NHL continued that set up through 1921.) What we think of as the modern playoff format was introduced by the Patricks in the PCHA in 1917-18. Their system pitted the top two teams against each other at the end of a full slate of regular season games.

than this when they created sports first modern playoff format.

The reason the Patricks gave for introducing their new format was that a second-place team might be coming on strong at the end of a season while a first-place team was struggling to hang on after a fast start. Perhaps the second-place team was truly the better team by the end of the season, and didn’t they deserve a chance to go after the Stanley Cup? But if even it hadn’t dawned on them right away (which it probably did!), the Patricks quickly realized that the playoffs kept up fan interest in cities that might otherwise be out of contention … and that these new postseason games were a pretty good way to make a buck!

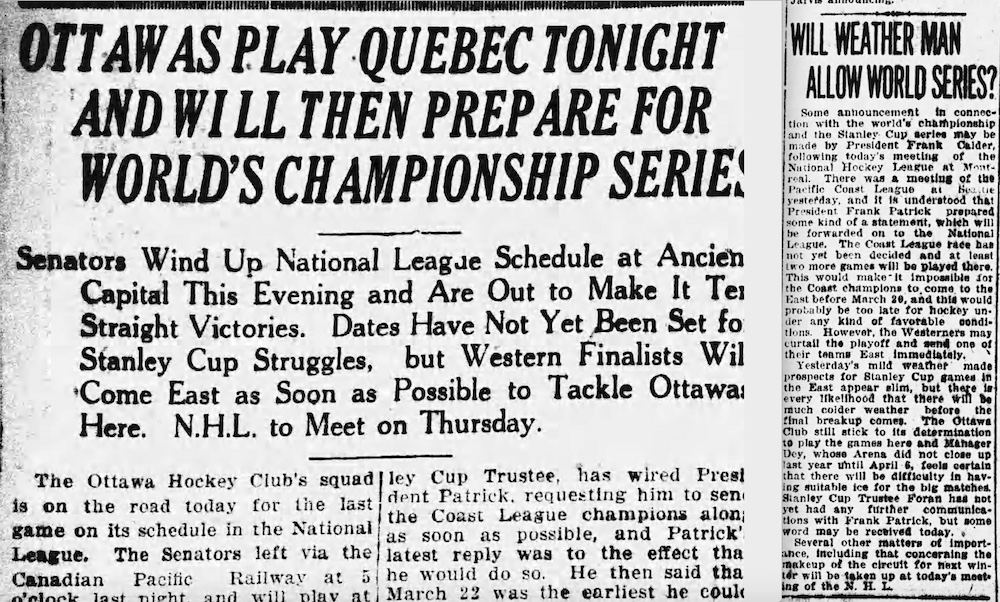

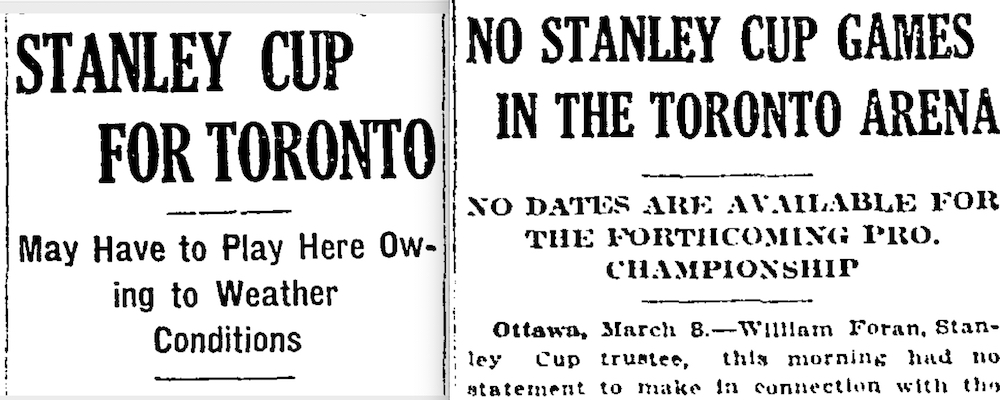

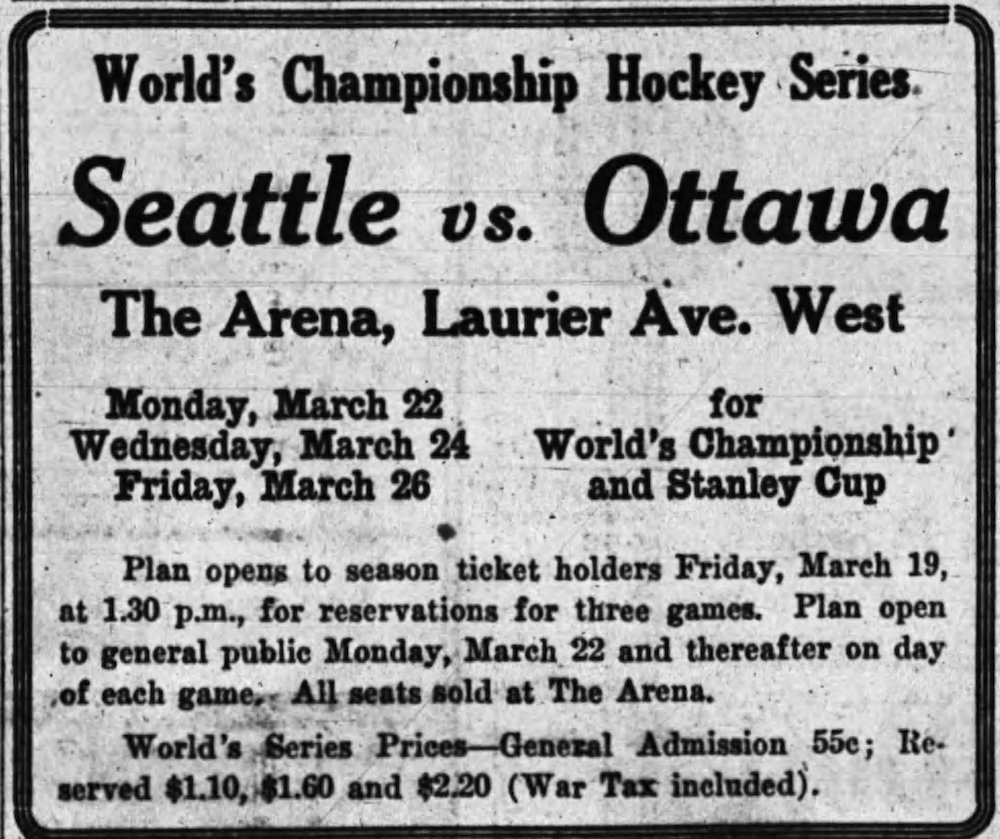

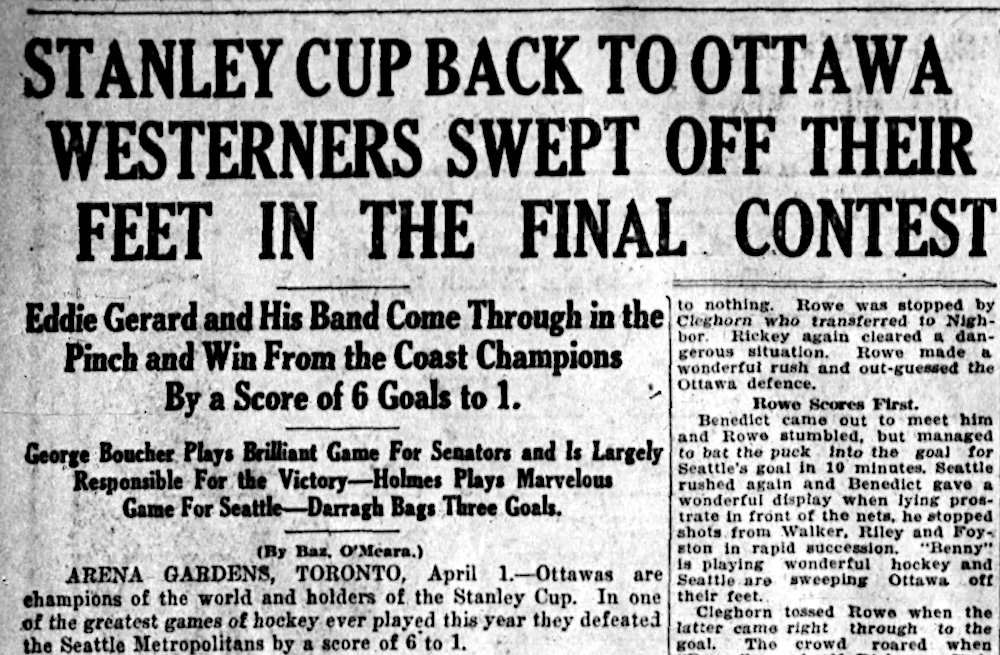

This reality was hammered home to the NHL in 1924 after Frank Patrick’s Vancouver Maroons finished in second place in the PCHA standings, and then eliminated the first-place Seattle Metropolitans. A new league – the Western Canada Hockey League – had emerged onto the Stanley Cup scene in 1922, but there was no real consensus yet on how to work out a three-team playoff. Frank Patrick decided that his team should play a best-of-three series against the WCHL champion Calgary Tigers en route to Montreal … even though both Western teams would still have a chance to face the Canadiens for the Stanley Cup. This angered NHL executives.

“When we arrived in Montreal,” Frank recalled, “[Canadiens owner] Leo Dandurand wouldn’t even speak to me. He staged a party for the Western clubs and invited everybody but me. Finally, after a couple of days, Leo weakened and ask me what we had played the bye series for. ‘For $20,000,’ I calmly replied. Then he laughed. He knew what I meant.”

What Patrick meant, of course, was the Western teams’ profits from the gate receipts of those three extra playoff games!

Both the PCHA and the WHL were gone from hockey by 1927, leaving the NHL as the only top pro league remaining. Their playoff formats got more and more elaborate after that. And when the Great Depression was turning baseball into a money loser during the 1930s, Lester Patrick – then running the New York Rangers – suggested that baseball should expand its playoff format as hockey had done. Americans mostly laughed at the idea. Right up until 1968, the teams that finished the season in first place in the American League and the National League advanced directly to the World Series. Additional playoff rounds weren’t introduced in Major League Baseball until 1969.

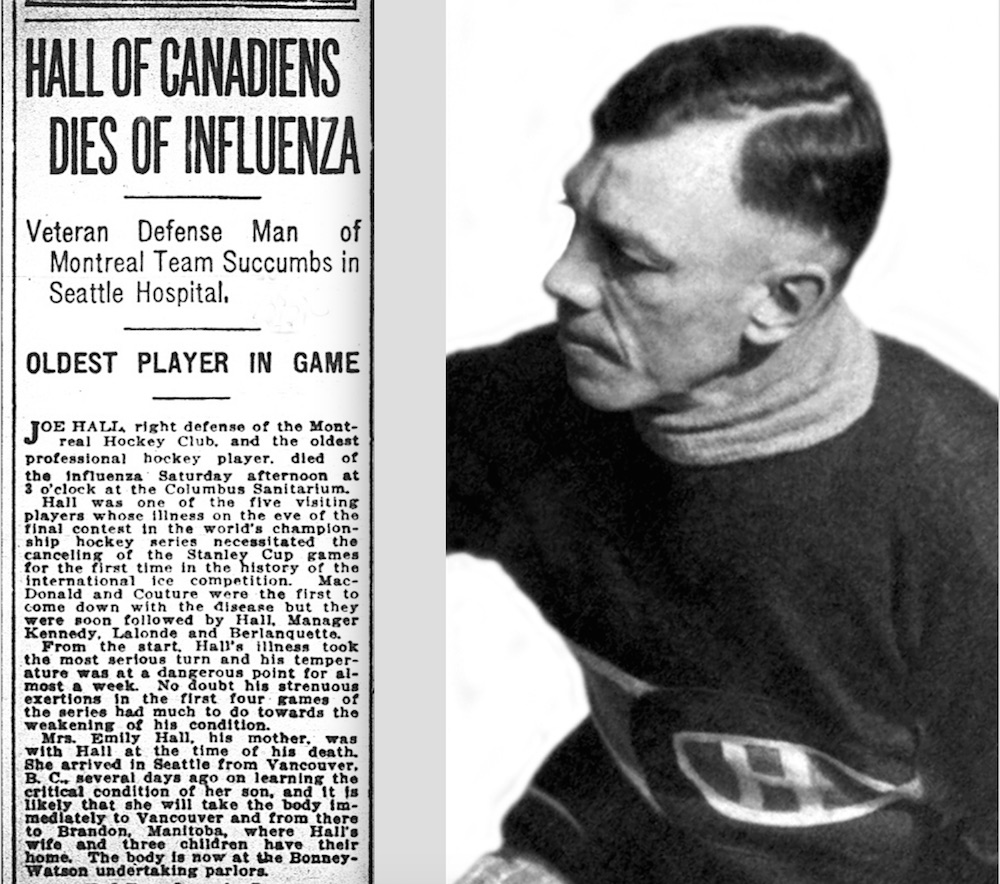

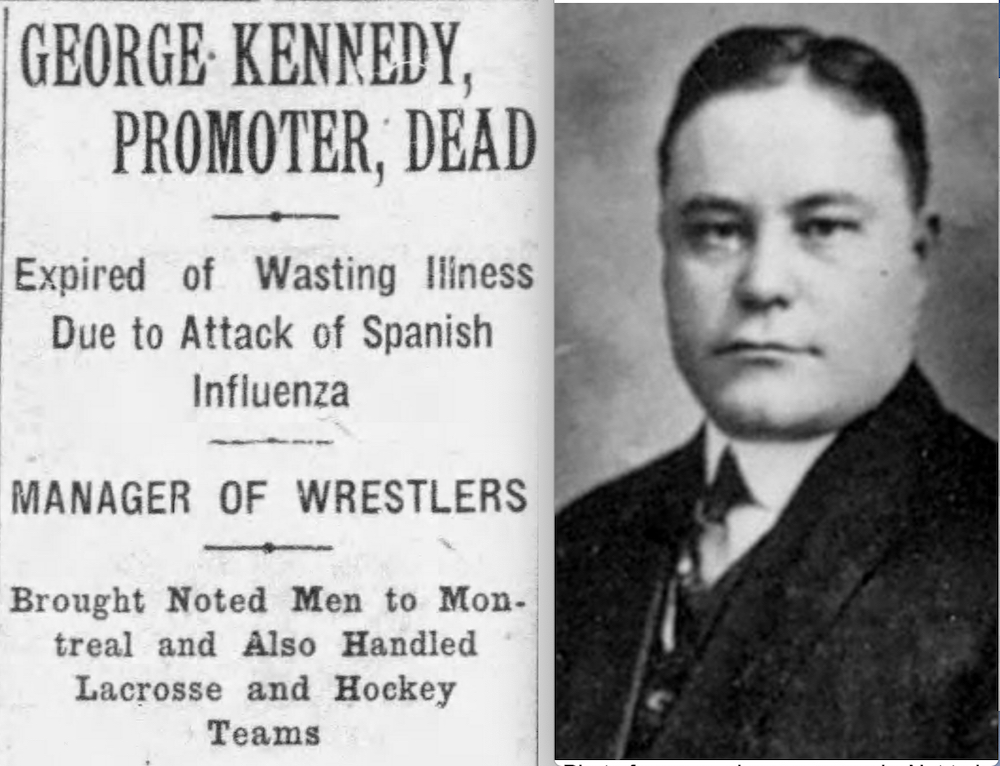

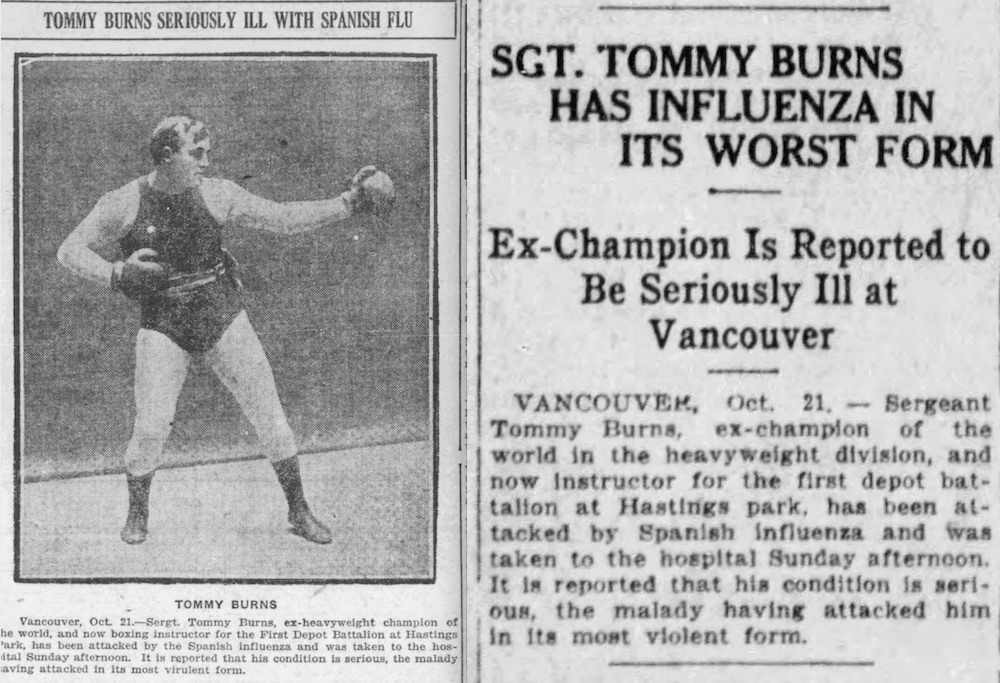

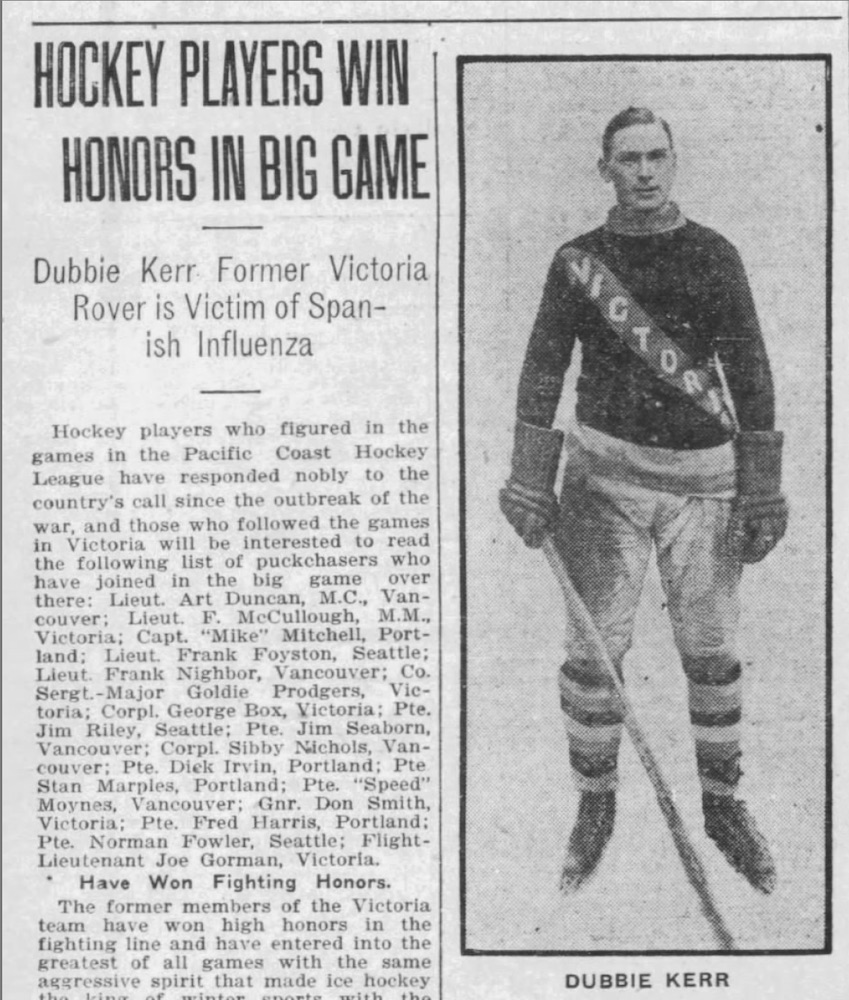

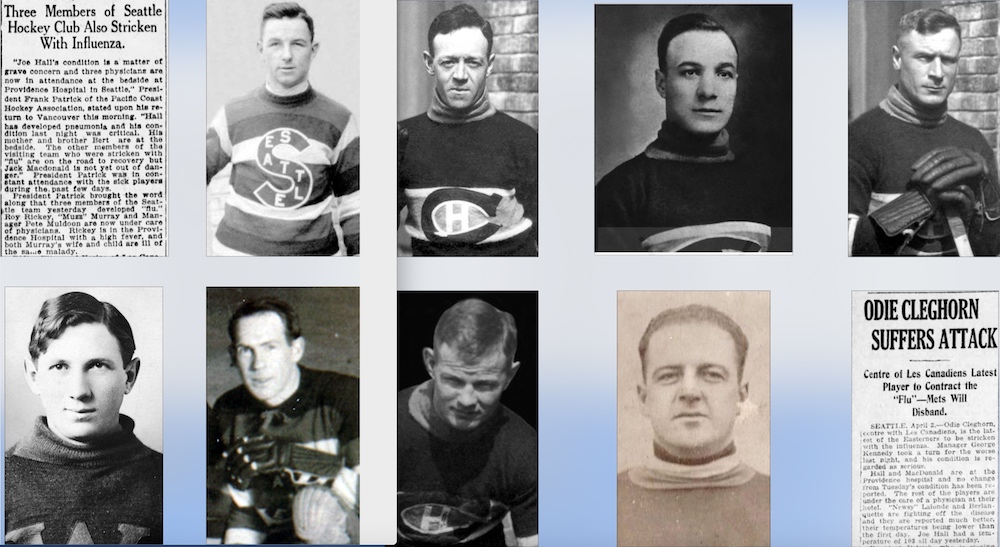

If baseball manages to get going this summer, they’re talking about expanding their playoff format from 10 teams to 14. So it’s not just the NHL that’s experimenting. Back in 1919, people thought the Spanish Flu was all but over when they started the Stanley Cup playoffs, and that turned out to be fatal. Let’s hope they won’t be experimenting with people’s lives this time.